Thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) occurs when there’s compression of nerves or blood vessels in your lower neck and upper chest. Symptoms include pain, tingling and numbness in your arms and hands. Common causes include vigorous arm movements (especially in sports), traumatic injuries and anatomical variations you’re born with.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/17553-thoracic-outlet-syndrome-illustration.ashx)

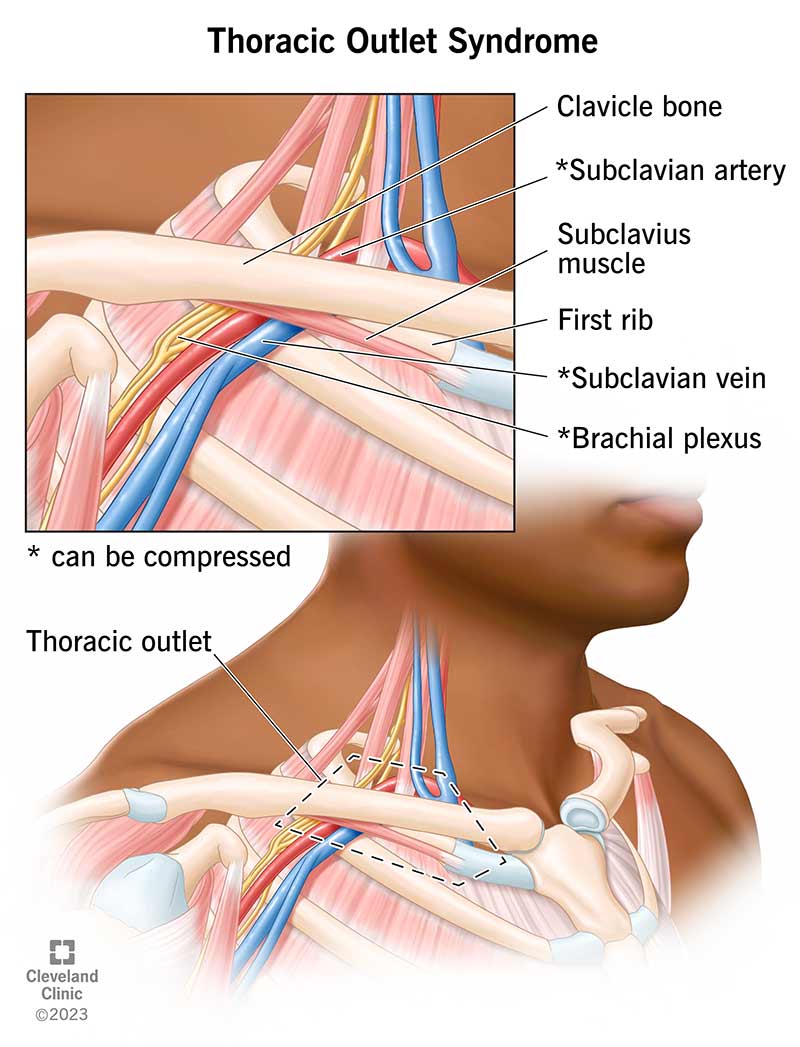

Thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) is a group of disorders that happen due to compression of nerves or blood vessels in your lower neck and upper chest. “Thoracic outlet” is an anatomical term that refers to the opening between your neck and chest. This opening (also called your thoracic inlet or superior thoracic aperture) is a passageway for many important structures. These include your brachial plexus (nerves that cross from your neck to your armpit), subclavian artery and subclavian vein.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Normally, your thoracic outlet is wide enough to allow these nerves and blood vessels to pass through easily. But certain anatomical variations and injuries can disrupt this passageway and make it too narrow. When that happens, other structures in your chest (like bones or muscles) press on the nerves or blood vessels within this space. This compression can cause pain, abnormal sensations (paresthesia) and other symptoms in your upper body. The wide range of symptoms, which could point to many possible problems, can challenge and delay diagnosis.

Conservative treatments like physical therapy and pain medications help most people. But you may need surgery if those methods don’t work or if TOS interferes with normal blood flow.

Healthcare providers classify TOS according to what’s compressed:

Advertisement

The term “vascular thoracic outlet syndrome” refers to the venous or arterial types. These types usually require surgery to relieve symptoms and lower the risk of complications. Neurogenic TOS often responds well to physical therapy and exercise, but some people need surgery.

Researchers estimate that each year:

The actual number of people who have this condition is likely higher than these numbers reflect because of challenges with diagnosis.

Thoracic outlet syndrome symptoms affect your upper body (neck, upper chest, shoulder, arm or hand), typically on one side. You may have:

The specific symptoms you feel can vary depending on the type of TOS you have. That’s because symptoms result from compression of specific structures (nerves or blood vessels). This compression prevents those structures from doing their normal job. Here’s a breakdown:

Thoracic outlet syndrome can cause pain in your neck, upper chest, shoulder and arm. This may feel like a dull ache, and it may worsen when you move your arms.

Some people confuse thoracic outlet syndrome pain with angina. Angina is chest pain you feel when your heart muscle doesn’t receive enough oxygen. But there are some important differences:

It’s important to keep in mind that TOS shares some symptoms with heart attack and stroke, which are medical emergencies. For example:

Advertisement

Seek medical care right away if you have symptoms of a heart attack or stroke. These are medical emergencies that need immediate attention. Delaying care for a heart attack or stroke can be fatal.

Healthcare providers divide the causes of TOS into three main groups:

Congenital factors predispose some people to TOS, but they may not feel any symptoms until there’s trauma to their neck from a sudden injury or chronic overuse.

Advertisement

You may face a higher risk of developing thoracic outlet syndrome if you:

Without treatment, thoracic outlet syndrome can lead to serious complications, including:

Healthcare providers diagnose TOS by performing a physical exam and reviewing your medical history. As part of your physical exam, your provider may ask you to do movement-based tests, including:

For these tests, your provider asks you to perform simple movements like lifting your arms, tilting your head and clenching your fists. They’ll see which movements trigger pain or other symptoms. The results can help with diagnosis.

Advertisement

Providers order lab and imaging tests as needed to confirm TOS and rule out other causes of your symptoms.

You may need one or more of the following tests:

These tests help your provider:

Thoracic outlet syndrome treatments vary, depending on the type of TOS you have and your symptoms. The goals of treatment are to reduce symptoms and prevent complications. Your provider will recommend the treatment option that’s right for you.

Possible treatments include:

Don’t wait for your symptoms to go away. Seek medical care if you have symptoms of TOS. While in many cases, conservative measures like physical therapy alleviate symptoms, some people need surgery or other treatments to prevent serious complications. Your provider will tell you the treatment plan that’s appropriate for your needs.

The outlook for people with thoracic outlet syndrome varies based on the type. Your healthcare provider is the best person to ask about what you can expect going forward.

You can’t always prevent TOS. Many of the causes are beyond your control. But there are some things you can do to lower your risk:

Follow your healthcare provider’s guidance on how to take care of yourself if you have TOS. Your provider may recommend you:

Call your provider if you have new or changing symptoms. They’ll tell you how often you need to come in for follow-ups and tests.

Here are some questions you can ask if you recently received a diagnosis of thoracic outlet syndrome:

Thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) can interfere with your usual routine. It may feel frustrating to take time away from your sport or slow down your pace at work. But be patient. Taking care of yourself with physical therapy or other treatments will help you regain your strength and feel much better in the long run. Talk to your provider if you have any questions or concerns about your condition, treatment plan or outlook.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Vascular disease may affect your life in big and small ways. Cleveland Clinic’s specialists treat the many types of vascular disease so you can focus on living.