The morning after her heart catheterization at Cleveland Clinic, 24-year-old Dorinda Bush Jones got a visit from her physician, a trailblazing open-heart surgeon named Dr. Donald B. Effler.

“He stopped at the foot of my bed, wiggled my left big toe and said to me, ‘Now go have your babies,’” Dorinda says. “My heart was singing.”

That procedure, performed to lessen the risk of complications and heart strain during any subsequent pregnancies, took place in 1970. It was 13 years after Dorinda became one of the first patients to undergo what was then called “stopped heart” surgery by Dr. Effler.

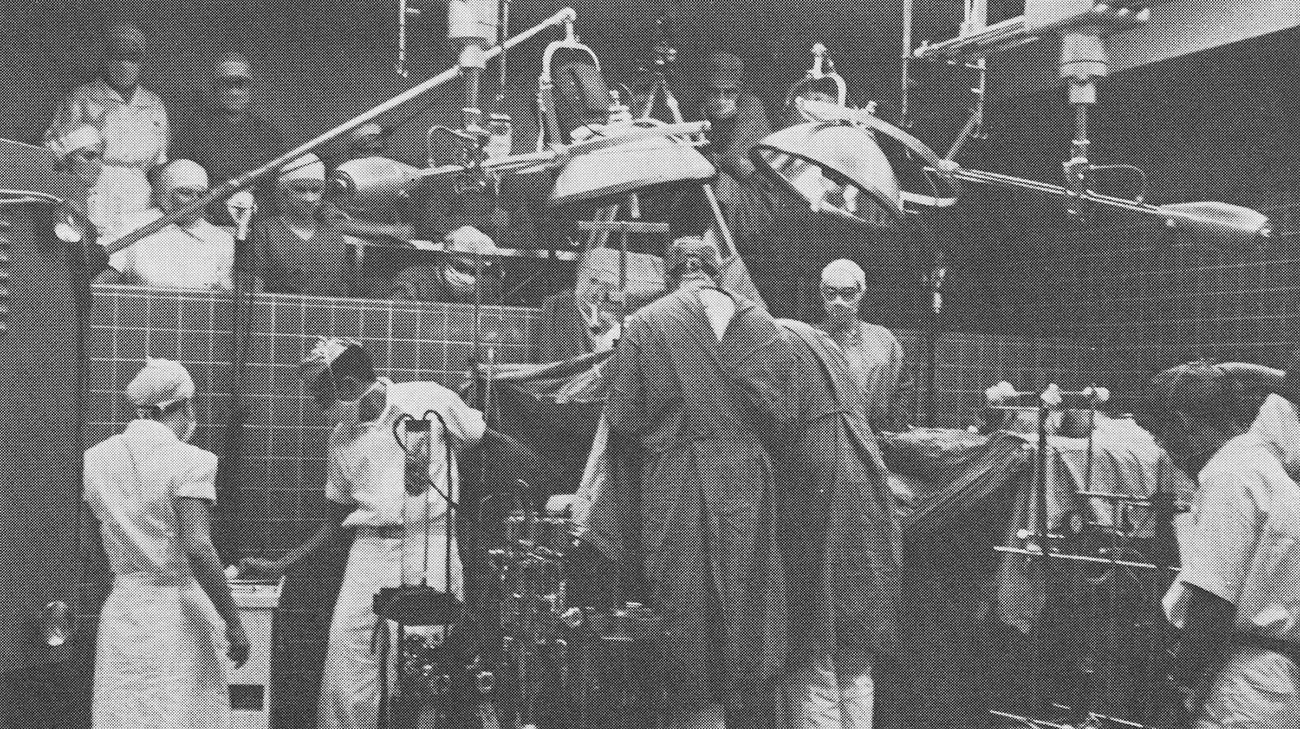

Dr. Donald Effler performed a stopped-heart operation in 1956, and 11 months later, performed the same procedure on Dorinda. (Courtesy: Cleveland Clinic)

Dorinda’s been a regular Cleveland Clinic patient ever since. 2021 marks the 100th anniversary of Cleveland Clinic, and the 65th year Dorinda has been treated by cardiologists and other specialists at the hospital. She was born with a group of birth defects called Tetralogy of Fallot, which alters the way the heart works.

“That she's been coming here for 65 years is a real testament to who we are and what we can offer. Cleveland Clinic has so many pioneers who develop state-of-the-art treatments,” says Mina Chung, MD, a cardiac electrophysiologist who has treated Dorinda since 1998. “And she’s seen a lot of them.”

Dorinda was growing up just as the Cleveland Clinic itself was entering its own formative years and becoming a leading heart institution. Born in Cuyahoga Falls, Ohio, but living much of her childhood on a farm in middle Tennessee, she was just a youngster when diagnosed with Tetralogy of Fallot. The rare disease is comprised of four heart defects and was virtually untreatable in the early 1950s.

Her childhood doctor referred to her as a “blue baby,” due to the bluish tint of her skin, lips and fingernails from low blood oxygenation. “There really wasn’t anything to do about it, so we just went along with our business,” recalls Dorinda, who would pause anytime she got winded when walking and often passed out during her childhood years. She even spent a tumultuous semester at a school for handicapped children when she was in first grade.

During her childhood, Dorinda’s skin had a blue-grey tint, one of the side effects from Tetralogy of Fallot. (Courtesy: Dorinda Jones)

Finally, during a summer back in Ohio, in 1957, her pediatrician in Akron, Ohio, recommended Dorinda be examined at Cleveland Clinic. He personally setup Dorinda's first appointment. That’s where she met Dr. F. Mason Sones, later known as the father of coronary angiography and a pioneer in cardiac catheterization. She also met Dr. Effler, a World War II veteran who served as Chief of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery from 1949 to 1975.

Less than a year earlier, Dr. Effler had performed the first open-heart operation at Cleveland Clinic. Dorinda’s parents were naturally fearful this still-developing surgery would be used on their daughter.

Dr. Mason Sones (left) and Dr. Donald Effler (right), pioneering cardiac doctors at Cleveland Clinic, who treated Dorinda. (Courtesy: Cleveland Clinic)

“Dr. Effler took us on a tour of the cardiac hospital floor where we met a girl named Judy, about my age, who was recovering from her surgery,” Dorinda recounts. “I’m sure that gave my parents confidence and trust in him. I was grateful for this thoughtful gesture on Dr. Effler’s part. He knew my parents needed reassurance.”

The surgery, during which Dr. Effler closed a quarter-sized hole between her right and left ventricles and stretched out (using his thumb) a constricted pulmonic valve, was successful. So, too, was a subsequent heart catheterization later that year. Dorinda was well on her way to a healthier and productive life, going on to earn several college degrees and then embark on a long teaching career. She also had two children with Jerry, her husband of 51 years.

Dorinda and her husband, Jerry, live in Cedarville, Ohio. (Courtesy: Cleveland Clinic)

However, Cleveland Clinic was – quite literally – never far from her heart. Over the decades, Dorinda has returned countless times for checkups and procedures necessary to keep the effects of Tetralogy of Fallot in check.

When she began to experience arrhythmia in the 1990s, Dr. Chung performed a number of catheter ablation procedures, during which a thin, flexible tube is inserted into the heart from a small incision made in the groin. A radiofrequency current would rid the area of scar tissue.

Ultimately, Dorinda would require a pacemaker be inserted to regulate her heart, a procedure performed at Cleveland Clinic by Mohamed Kanj, MD, in 2011. A few years later, she underwent another innovative procedure, performed by Lourdes Prieto, MD, to replace a damaged pulmonic valve without need for open-heart surgery.

Through it all, Dorinda has continued to live a full, productive and active life.

Dorinda and Jerry have five grandkids, MJ (left), Zach, Andrew and Molly (center) and Olivia (right). (Courtesy: Dorinda Jones)

“You know, if Dr. Sones or Dr. Effler were here to see her today, I think they'd be proud that their work has really helped her,” Dr. Chung observes. “She's seen the development of medical technology to deal with her problems, and through it all, she's been really positive.”

Dorinda thinks of her life as a tapestry, and Cleveland Clinic as one of its most important threads. “My getting from the hills and dirt roads of Tennessee to Ohio is a thread, and Cleveland Clinic is a thread,” she says. “And then God brought the two threads together, with his thread, tied them up and we've been together ever since.”

Related Institutes: Heart, Vascular & Thoracic Institute (Miller Family)