If you volunteer to become a living liver donor, your liver can save a life while you’re still alive. It only takes a piece of your liver to grow into a full-sized liver in another person. Your liver will also grow back to full size. Here’s how living donor liver donation and transplantation works.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/Images/org/health/articles/21083-living-liver-donation-transplant.jpg)

Most organ donations for organ transplants come from deceased donors. But the liver is special. The liver is the only organ that can regenerate itself and grow back from a small piece to its full size. This means that a living donor can volunteer to donate a part of their healthy liver to someone else in need. Miraculously, when you become a living liver donor, your healthy liver can become two healthy livers.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

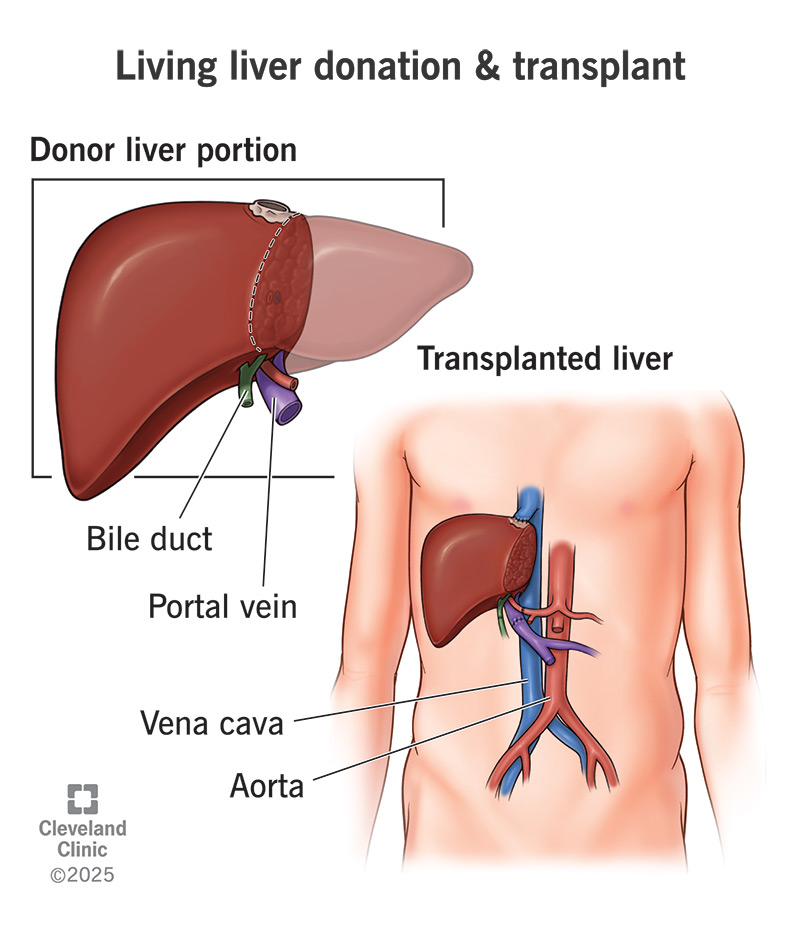

A living donor liver transplant is two procedures that happen simultaneously: one for the liver donor and one for the transplant recipient. If you donate, a surgeon will remove a portion of your liver — typically one lobe, or less for a child — and transplant it in the recipient right away. After a successful living liver donation and transplant, both pieces of the divided liver will grow back to full size within a few months.

If you and your liver are in good health, you could become a living liver donor and save a life. You can’t always donate your liver to a particular person you know — it depends on if your blood type and liver mass is compatible with theirs. But when you donate a part of your liver to someone in need, you reduce the greater need. This makes it more likely that another donor liver could save the person you know.

Video content: This video is available to watch online.

View video online (https://cdnapisec.kaltura.com/p/2207941/sp/220794100/playManifest/entryId/1_3ire78f7/flavorId/1_5f3sgelj/format/url/protocol/https/a.mp4)

Dr. Koji Hashimoto explains why living donor liver transplant is lifesaving and beneficial for patients.

When you volunteer to become a living donor, you’ll begin a screening process. A team of healthcare professionals will thoroughly evaluate you to make sure you meet the requirements for liver donation.

The basic requirements for living liver donation are that:

Advertisement

To start the process, call your local organ transplant hospital or the hospital you wish to donate to. A coordinator will speak with you to gather some general information and answer your questions. If they believe you’re a candidate for liver donation, they’ll arrange for you to come to the hospital to continue your evaluation. You’ll take a variety of medical screening tests and consult with a variety of specialists.

You might meet with a(n):

After your tests and interviews, two independent teams will evaluate your offer. The first is a donor advocacy team. This team is primarily concerned with your safety. If they clear you for liver donation, they’ll recommend you to the liver transplant selection committee. This team will review your overall fitness to become a donor. They’ll make the final decision and select a recipient for your liver donation.

You may wish to donate a part of your liver to someone you know. This is called a “directed donation.” You can do this if your blood type is compatible and your liver size is comparable with theirs. If you’re not a match with your intended recipient, you can try a “paired exchange” program. That means you and your intended recipient pair up with another donor and recipient who don’t match, and you swap.

You can also donate freely to someone you don’t know. This is called a “non-directed donation.” Once you’re approved to donate, the transplant hospital will match you with a stranger on the waiting list. You can donate your liver anonymously or you can choose to meet your recipient if both of you wish to meet. The transplant team will protect your identity and their identity if you and they prefer that.

Once you and your liver recipient have been selected, the transplant team will coordinate with both of you to schedule your simultaneous procedures. When you have your date, you can begin to make arrangements. You can expect to stay in the hospital for a week after surgery. Recovery time at home may take up to six weeks. You may need to take time off from work or arrange for help with childcare.

You may also need to:

Meanwhile, your surgical team will prepare by thoroughly image-mapping your liver. They’ll take a comprehensive series of images, including 3D images, and analyze them to select which part of your liver to remove and determine the best surgical approach. At some transplant centers, minimally invasive surgery might be an option. If so, they’ll evaluate whether it’s feasible in your case.

Advertisement

You and your recipient — whether you know each other or not — will have surgery at the same time. While one surgical team removes a portion of your liver, another will remove the failing liver in your recipient, preparing to receive your donation. Your procedure will be shorter than theirs — about four to six hours. You’ll have general anesthesia, so you won’t feel any sensation or have any awareness during surgery.

You may have:

Your surgeon will select the section of your liver that they’ve predetermined to remove. They’ll carefully disconnect it from your blood vessels and bile ducts. After removing the piece, the transplant team will transfer it to your waiting recipient and begin the process of attaching it to their blood vessels and bile ducts. While this is in progress, your surgeon will close your incisions and finish your surgery.

Advertisement

More than 15,000 people in the U.S. each year join the waiting list for a liver transplant. Some are in the hospital with sudden liver failure, and only have days to recover. Others are in the end-stage of a long battle with chronic liver disease, and are steadily declining. Some have primary liver cancer that could be cured by a liver transplant, but only if it doesn’t spread first. For all of them, time is of the essence.

The longer they wait for a liver transplant, the sicker they become. If they become too ill to survive the transplant surgery, or if their cancer advances beyond their liver, it will be too late to save them. Each year, more than 2,000 die or become too ill waiting for a liver transplant from a deceased donor. If any of them had a living liver donor, they could bypass the waiting list and schedule their transplant surgery right away.

Living donor liver transplant recipients enjoy:

In addition, most living liver donors report:

Advertisement

Living liver donation is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. While your liver can regenerate after being divided, this takes a toll. Your liver can recover and continue to function well for you, but it doesn’t have an unlimited capacity to do this. A second surgery would be too stressful for your liver and raise your risk of complications to an unacceptable level. So, transplant teams don’t accept repeat donations.

Any surgery performed under general anesthesia comes with a risk of complications, like:

Additional risks associated with liver surgery include:

There is a small chance of liver failure or death after liver donation. According to a previous report, the chance of death after liver donation is 0.2% (1 in 500 living donors).

Beyond the physical risks, you may want to consider other ways that being a living liver donor might negatively affect you, either psychologically or practically. Some of these may include:

Liver donation doesn’t appear to affect long-term health. General health and quality of life scores in previous liver donors are equal or greater than in the general population.

Some people have reported lingering fatigue, gastrointestinal issues or psychological issues after surgery. But these are not expected outcomes. With proper support from your healthcare team, they should resolve with time.

For the living donor, life after liver donation will go back to normal in stages. You’ll spend about a week in the hospital after surgery. This will be the most intensive part of your recovery. You’ll have various tubes installed to manage your pain, deliver fluids and drain your bladder. After that, you’ll gradually start moving, eating and going to the bathroom on your own.

You can expect:

If you’re considering a living liver donation, you’ll be making one of the most important decisions of your life. It’s important to take as much time as you need to absorb all the information you’ll be presented with and to process all the feelings involved. Make sure you fully understand the procedure, its potential risks, what to expect from the recovery process and what the potential outcomes might be.

The prospect that you could save a life with only a short-term sacrifice is very powerful. As you weigh the costs and rewards, don’t hesitate to consult your transplant team with any additional questions and concerns that may arise. They’re here to advocate for your health and safety and to help you make an informed and confident decision. Remember, your team is entirely on your side, whatever you decide.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Hearing you need a liver transplant can be life-changing. But Cleveland Clinic is here for you with expert care that’s focused on you every step of the way.