Your urinary tract is a one-way street from your kidneys down to your urethra. VUR (vesicoureteral reflux) is when your pee goes in the wrong direction, back up your ureters. It affects newborns, toddlers and children most often, but VUR usually isn’t typically painful or long-lasting, and treatment is available.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/vesicoureteral-reflux)

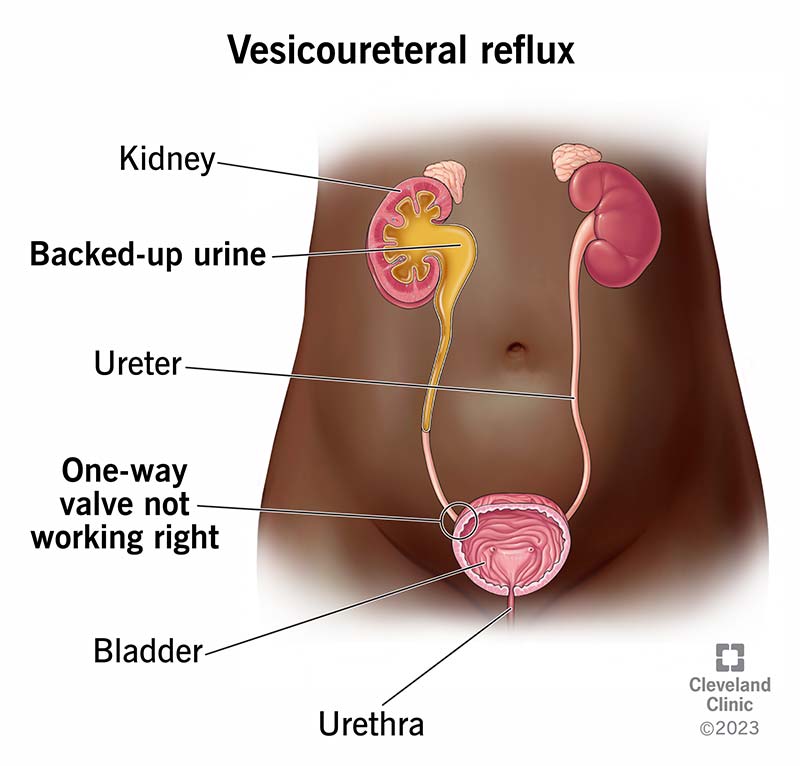

Vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) is a condition where pee (urine) flows in the wrong direction. Instead of flowing from your kidneys, down into your ureters and bladder where it stays until you pee, your pee flows backward from your bladder.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Your urinary tract is typically a one-way valve, with pee flowing down your urinary tract. This valve-like mechanism prevents pee from going back up into your ureters after it gets to your bladder. Typically, pee should flow like this:

In VUR, pee flows back — or refluxes — from your bladder into one or both of your ureters and, in some cases, to one or both kidneys. It happens most often due to an issue that prevents the one-way valve from functioning as it should.

Vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) mostly affects newborns, infants and young children ages 2 and under, but older children and (rarely) adults can also have VUR.

Pee flowing the wrong way can cause bacteria to get into your child’s kidneys and cause infection. Kidney infections can cause permanent kidney damage when left untreated.

Treatment for VUR depends on the severity of your child’s symptoms, age and other factors. Mild cases may not need treatment and some children outgrow VUR. But some children need surgery or medication to treat VUR so it doesn’t cause kidney damage.

Advertisement

VUR that affects only one ureter and kidney is called unilateral reflux. VUR that affects both ureters and kidneys is called a bilateral reflux.

The two types of VUR are primary and secondary:

The stages of VUR are grades and there are five of them. Five is the most severe form of VUR and one is the mildest form. The grading system is based on:

The grade breakdown is:

About 1% to 3% of children have vesicoureteral reflux (VUR). About 75% of children with VUR are female.

In many cases, a child with vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) has no symptoms. When symptoms are present, the most common is a urinary tract infection (UTI). Some estimates show that 30% to 50% of children with a UTI have VUR.

Symptoms of a UTI in a child include:

Advertisement

Noticing signs of UTI in an infant can be more difficult. They may show signs of fussiness or lose their typical appetite.

No, vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) isn’t painful. But if there is a UTI, that can come with pain during urination and pain in the kidney/abdominal region.

The two types of vesicoureteral reflux (VUR), primary and secondary, have different causes.

Advertisement

Risk factors for VUR include:

Complications of vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) in children include:

Most children with VUR recover without long-term complications.

Adults with vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) typically have benign prostate hyperplasia, neurogenic bladder or they had surgery near their ureters.

Yes. It can also cause kidney stones and stones in other parts of your urinary tract like your bladder.

Advertisement

Vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) itself isn’t life-threatening. However, VUR can lead to recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs), which can cause kidney scarring and then worsen into renal hypertension (high blood pressure from kidney disease) and kidney disease. End-stage kidney disease requires dialysis and/or a kidney transplant.

Pediatric nephrologists and pediatric urologists are medical doctors who focus on kidney and urinary tract conditions. It’s likely your pediatrician will refer you to one or both of these specialists for your child’s care.

They may order the following tests to diagnose vesicoureteral reflux (VUR):

If your child receives a vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) diagnosis, they should have the following tests regularly:

Your child’s healthcare provider may also evaluate them for bladder and bowel dysfunction (BBD). Symptoms of bowel and bladder problems include:

Children who have VUR along with any BBD symptoms are at greater risk of kidney damage due to infection.

Managing VUR requires the help of a healthcare provider. Treatment options depend on your child’s age, symptoms, type of VUR and its severity. Treatments include antibiotics and other medications, an injectable dissolvable bulking agent, short-term catheterization and surgery. You and your pediatrician and specialists will discuss these treatment options and make the best choice for your child’s VUR.

Primary VUR may improve with age (typically by age 5). Sometimes, a wait-and-see approach works. Other times, surgery or medications are necessary.

As your child gets older and their urinary tract anatomy grows and matures, primary VUR will often improve. Until then, your healthcare provider will prescribe an antibiotic to treat or prevent a urinary tract infection (UTI).

Use of long-term antibiotics for the prevention of UTI is somewhat controversial. Extended use of antibiotics can lead to antibiotic resistance. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends preventive antibiotics mostly for children with higher grades of VUR (while waiting to see if they outgrow VUR).

Healthcare providers use several different surgical methods for primary VUR. The goal of surgery is to fix the connection point (one-way valve mechanism) between the bladder and ureters to prevent pee from flowing backward.

The gold standard procedure for surgical correction of VUR is called a ureteral reimplant. The goal of the reimplant is to create a flap-valve mechanism, which means re-routing the ureter in the bladder wall with an appropriate length of tunnel so urine doesn’t reflux back up into the ureter. Your child’s surgeon can perform this procedure with an open surgery (incision in your child’s abdomen) or laparoscopically. Your child’s surgeon can discuss the benefits and risks of each method with you, as well as possible side effects. Surgery requires general anesthesia, and possibly, a short hospital stay.

Another type of procedure for primary VUR is the use of hyaluronic acid/dextranome (Deflux®), a gel-like liquid. Your child’s provider injects a small amount into your child’s bladder wall near the opening of the ureter. This injection creates a bulge in the tissue and acts like a valve that makes it harder for pee to flow backward. It’s an outpatient procedure (your child goes home the same day), but still requires general anesthesia. Your child’s provider can discuss the risks and benefits of this type of treatment with you.

Healthcare providers treat secondary vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) by removing the blockage or improving how the bladder empties. Treatment may include:

If your child receives a VUR diagnosis, work closely with their healthcare team on a treatment plan that works for your family. Managing a condition like VUR can have an effect on you and other caregivers. Be sure to discuss your concerns with your child’s healthcare team. The good news is that VUR is highly treatable and most children don’t have long-term effects from it.

Your child should have vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) for less than a year, but an exact timeline depends on your child’s condition. Your child’s healthcare provider may recommend a wait-and-see approach or they may suggest surgery if they see severe VUR or kidney damage on imaging tests.

Yes. It’s possible for your child to grow out of VUR, especially if they have a lower grade (one or two) of primary VUR. Children may outgrow this type within a few years.

It depends on the severity of their symptoms. Remember, VUR itself isn’t disruptive to your child’s day-to-day living, but UTIs can be. Although not contagious, your child may be in pain or have problems with constipation or incontinence. Meet with your healthcare provider to discuss options for returning to school and participating in playdates.

There isn’t a known way to prevent vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) — not with food, lifestyle changes or medication. But there are steps you can take to improve your child’s overall urinary tract health. Make sure your child:

Help your child to be healthy by encouraging exercise and making sure meals are balanced and nutritious.

See your child’s pediatrician if you suspect a UTI, as this is often the first sign of VUR. Other signs like urinary incontinence, unexplained fever or painful urination can also suggest VUR. Your pediatrician may send you to a specialist if they suspect VUR.

Have a conversation with your child’s healthcare provider to get answers to all of your questions about vesicoureteral reflux (VUR). Some questions you can ask include:

Remember that vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) isn’t usually painful or life-threatening. It’s manageable and treatments are usually successful. There’s no way to prevent it, but make sure to have your child drink plenty of water, get exercise and eat nutritious meals to maintain their overall health. Rely on your healthcare provider’s expertise. They’ll help diagnose and treat your child’s VUR. Don’t hesitate to contact them with questions and concerns, and be open and honest about your child’s symptoms, even if they’re awkward to talk about.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

If you have a condition that’s affecting your urinary system, you want expert advice. At Cleveland Clinic, we’ll work to create a treatment plan that’s right for you.