Having aniridia means your child might have permanently impaired vision. Talk to your provider about how often you should see an eye care specialist. It’s important to get any changes in your child’s eye checked as soon as possible. This will help you catch complications like glaucoma and cataracts right away.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/aniridia)

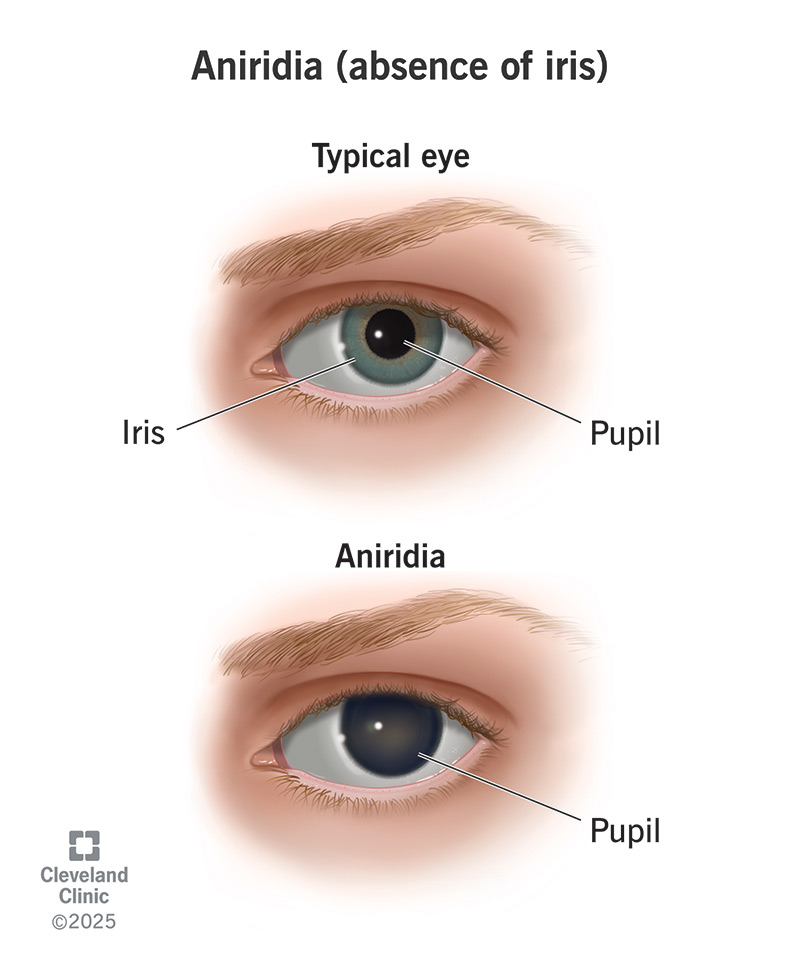

Aniridia is a condition that causes babies to be born without irises (the colored part of your eye). Some babies are missing their entire irises. Others only have part of an iris in each eye.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Aniridia always affects both of your child’s eyes (it’s a bilateral condition).

A healthcare provider will probably diagnose aniridia when your child is born. They’ll be able to see the missing iris in your child’s eyes. No matter how much of your baby’s irises are missing, aniridia will affect their vision and can eventually lead to other issues in their eyes later in life.

Because your child is missing their irises, their pupils will look larger than usual. Their pupils might be unevenly shaped. They’ll have a hard time adjusting to changes in lighting. This can lead to symptoms like:

Aniridia is genetic disorder. It happens when a genetic change affects the PAX6 gene. This gene helps form your baby’s eyes and parts of their brain, spinal cord and pancreas. The genetic change that causes aniridia usually happens between the 12th and 14th week of pregnancy.

Aniridia is more common in children whose biological parents have it. If one parent has aniridia, there’s a 50/50 chance their biological child will, too.

So, if you have aniridia, that doesn’t guarantee that your biological children will have it. It just means they’re more likely to.

Advertisement

Aniridia can also happen on its own (sporadically) even if neither biological parent has it. This happens in around 1 in 3 cases.

Other parts of your child’s eyes might be underdeveloped, as well, including their optic nerves and retinas.

Children with aniridia are likely to develop other eye issues as they grow up, including:

Children with sporadic aniridia have a higher risk of developing a Wilms tumor (a rare type of kidney cancer). The genetic change that causes sporadic aniridia is much more likely to impact other parts of your child’s body that the PAX6 gene is responsible for.

Your provider will diagnose aniridia when your baby is born. You should be able to see the missing irises in your baby’s eyes.

If you’re pregnant and concerned about the fetus’s risk of aniridia (or other genetic disorders), talk to your provider about prenatal genetic testing. Your provider will use a blood test to tell how likely it is that the fetus could have a genetic disorder. They might also perform amniocentesis — removing and testing a small amount of your amniotic fluid.

Treating aniridia focuses on maintaining or improving your child’s vision.

Your child will need regular eye exams and visits with an eye care specialist. The sooner your provider diagnoses changes in your child’s eyes, the more likely they’ll be able to prevent symptoms or complications.

Your child might need a few treatments, including:

See a healthcare provider as soon as you notice any changes in your child’s eyes or vision. You might want to ask your provider questions like:

Advertisement

Go to the emergency room if your child has any of the following symptoms:

You should expect your child to have vision issues. Your child will need regular eye exams throughout their life to monitor their eye health.

More than 8 in 10 children with aniridia have poor or impaired eyesight. Most people with aniridia develop glaucoma, usually when they’re 10 to 20 years old.

But this doesn’t mean every baby born with aniridia will definitely face these issues. Talk to your provider or eye care specialist about what to expect as your child gets older.

It can be scary to find out your baby has a condition that will affect their vision from birth. Aniridia can cause lots of issues, but treatments can help.

Regular visits with your healthcare provider or eye care specialist will be the key to keeping your child’s eyes healthy and protecting their ability to see. Talk to your provider as soon as you notice any changes in your child’s eyes. The sooner an issue is diagnosed, the better.

Advertisement

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

When you need care for your child’s vision, it’s important to find someone you trust. Cleveland Clinic Children's experts focus on your child's needs.