Junctional tachycardia is a rare, fast heart rhythm that starts in the wrong place in your heart. Treatments include medicines, using an external pacemaker to correct your heart rhythm or a catheter ablation to keep the wrong signal from traveling. Ablation works for many people, but you may need to have it more than once.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/23216-junctional-tachycardia)

Junctional tachycardia (junctional ectopic tachycardia) is a rare heart rhythm that starts from a natural pacemaker, but not the one your heart normally uses.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

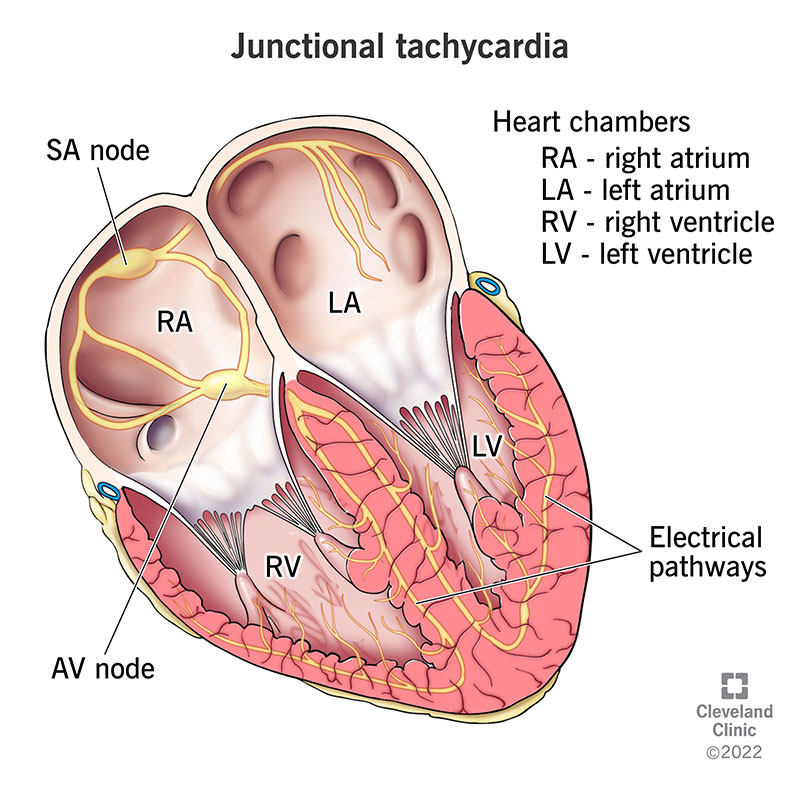

Usually, your heartbeat starts in your sinoatrial node and travel down through your heart. This is called normal sinus rhythm. Sometimes, your sinoatrial node is injured and can’t kick off your heartbeat. When that happens, the heartbeat might start in your atrioventricular node (the junction of your heart’s lower and upper chambers). This is similar to an understudy in a play taking over for the lead actor when they’re sick.

A normal resting heart rate typically ranges from around 60 to 100 beats per minute. With junctional tachycardia, your heart rate is typically faster than 100 beats per minute.

There are two types of this abnormal heart rhythm.

Yes, junctional tachycardia is a type of SVT, or supraventricular tachycardia. An SVT is a fast heart rhythm (tachycardia) that starts in the upper chambers of your heart, above your ventricles (supraventricular).

Advertisement

Junctional tachycardia is rare in adults, but more common in babies and children. It can be from a congenital (present at birth) cause, which is very rare or happen after heart surgery.

You might not have symptoms of junctional tachycardia. If you have symptoms, they may include:

Several medicines, conditions or treatments can get in the way of your sinoatrial node making electrical signals to start your heartbeat.

For example, toxicity from digoxin (Cardoxin® or Digitek®) may cause junctional tachycardia. Other causes include:

Junctional tachycardia is diagnosed by an electrocardiogram (ECG), which shows a missing “P wave,” the signal that represents the sinoatrial node starting a normal heartbeat. In addition to the ECG, your healthcare provider will take your medical history and may order additional tests including blood tests and an echocardiogram (ultrasound of the heart).

Treatment depends on the underlying cause and on your symptoms. If your abnormal rhythm started after heart surgery, your healthcare provider may:

Other treatments may include:

With catheter ablation, there’s a chance the abnormal rhythm will happen again. There’s also a risk of an atrioventricular (the next signal carrier after the sinoatrial node) block for catheter ablation in adults. Your healthcare provider may use cryoablation instead because it has a lower risk of atrioventricular block. If ablation doesn’t work after a couple of attempts, you may need a pacemaker.

Usually, after catheter ablation, you can go back to your normal activities the day after going home. You’ll need to wait several days before doing anything strenuous. Your healthcare provider will give you specific instructions after your procedure.

Symptoms go away gradually when you treat the cause of this abnormal rhythm. You’ll need to be in the hospital until your junctional tachycardia goes away.

Advertisement

The outlook for junctional tachycardia is different depending on the type.

Primary or congenital (since birth) junctional tachycardia is harder to treat and can lead to heart failure, complete heart block or ventricular fibrillation. Up to 9% of cases are fatal without treatment. If this rhythm starts after the first six months of life, the outlook is much better.

Secondary or postoperative (after surgery) junctional tachycardia shows up two or three days after surgery but often goes away a week afterward. It may cause low blood pressure, dizziness or passing out.

Your healthcare provider may be able to give you certain medicines before or during surgery to reduce your risk of junctional tachycardia. These medicines may include:

You’ll need to have a follow-up appointment with your provider two weeks after you go home from the hospital. You’ll also need care for the condition that caused junctional tachycardia.

You should get help right away if you had a catheter ablation and the place where the catheter went into your skin:

Advertisement

If your child has junctional tachycardia, ask your healthcare provider to explain the symptoms so you can recognize it if it happens again. Don’t be afraid to ask questions about your child’s treatment. It’s important that you understand treatment options and risks. Being informed will empower you to make the best decisions for your child’s care.

Advertisement

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

When your heart rhythm is out of sync, the experts at Cleveland Clinic can find out why. We offer personalized care for all types of arrhythmias.