Mycosis fungoides is a type of skin lymphoma (cancer) that affects your body’s T cells. It occurs when these white blood cells become cancerous. Often, a skin rash is the first sign of mycosis fungoides. It doesn’t have a cure, but many people who receive timely treatment experience long periods with no symptoms.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/Images/org/health/articles/21827-mycosis-fungoides)

Mycosis fungoides (pronounced “my-KOH-sis fun-GOY-deez”) is a blood cancer that happens when white blood cells called T cells transform into malignant (cancer) cells. T cells are a kind of lymphocyte. Lymphocytes fight harmful pathogens in your body, like viruses and bacteria. With mycosis fungoides, T cells transform into cancer cells that affect your skin.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Mycosis fungoides is a type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL). CTCL is a group of rare blood cancers that cause changes in your skin, like itchiness, rashes, plaques or tumors.

Although mycosis fungoides affects your skin, it’s not a form of skin cancer because your T cells — not skin cells — become cancerous.

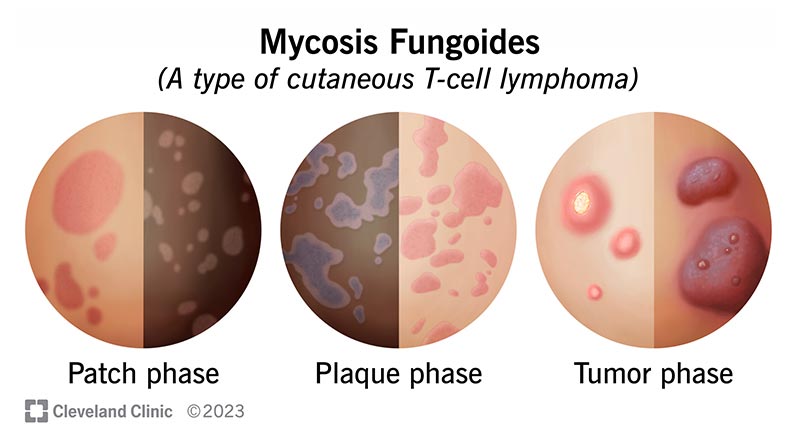

Mycosis fungoides symptoms occur in several stages of skin changes. Not everyone progresses through all the phases. Some may happen simultaneously.

For many people, the first sign of disease in the early stage is a mycosis fungoides rash. Mycosis fungoides stages include:

In the most severe stages, many cancerous T cells circulate in your blood. At this point, they’re called Sézary cells. High levels of Sézary cells may cause mycosis fungoides to evolve into Sézary syndrome. With this condition, you may develop a red rash all over your body, called erythroderma.

Advertisement

Experts don’t know what causes mycosis fungoides, but genetic mutations may play a role. Genetic mutations are changes in the genetic material inside a cell, like DNA or chromosomes. Many people with mycosis fungoides have missing genetic material or errors in the genetic material inside the cells that become malignant.

These genetic mutations don’t seem to be inherited (passed down through families).

Researchers continue to study other potential causes, such as exposure to certain environmental toxins and infections.

Mycosis fungoides isn’t contagious. It doesn’t spread from person to person.

It may be challenging to diagnose mycosis fungoides based on a visual skin exam because it can resemble other skin conditions. It’s easy to mistake mycosis fungoides for more common skin conditions during an exam, like eczema or psoriasis.

To confirm or rule out mycosis fungoides, your healthcare provider will likely perform additional tests such as:

Cancer staging is an important part of a mycosis fungoides diagnosis. Cancer staging classifies mycosis fungoides on a scale from I to IV based on how invasive it is and the extent it’s spread. Knowing the stage helps your healthcare provider determine treatments.

Stages IA through IIB are regarded as early-stage mycosis fungoides. Stages IIB through IVB are considered advanced disease.

When staging mycosis fungoides, providers consider various factors, including:

Mycosis fungoides treatment depends on the cancer stage and type of skin changes. Many treatment options focus on relieving symptoms and improving your quality of life.

Your healthcare provider may prescribe:

Advertisement

Healthcare providers rarely use traditional chemotherapy for mycosis fungoides. Chemotherapy doesn’t always effectively treat mycosis fungoides. It also carries a significant risk of side effects.

There isn’t a cure for mycosis fungoides. Although there’s no way to get rid of it completely, with early diagnosis and treatment, people often live for many years without symptoms. Most live a normal life span.

Your prognosis depends on multiple factors, with cancer stage being especially important.

It’s much easier to treat mycosis fungoides in its early stages. Many people who receive early diagnosis and treatment experience long periods with no symptoms.

More advanced mycosis fungoides may need more intensive treatment. For example, you may need radiation therapy or chemotherapy if cancer has spread beyond your skin.

The 10-year survival rate for early-stage mycosis fungoides is 95%. The life expectancy for advanced mycosis fungoides is three to five years, and it may be less if the cancer has spread beyond your skin.

Still, it’s important to remember that these numbers are just statistics. Your prognosis depends on various factors unique to you, including age, overall health and disease course. Your healthcare provider is your best resource for answering questions about what to expect with mycosis fungoides, including likely treatment outcomes and life expectancy.

Advertisement

There’s no proven way to prevent mycosis fungoides. You can reduce the risks of late-stage mycosis fungoides by scheduling regular appointments with a healthcare provider. Regular checkups can increase the chances of detecting mycosis fungoides in its early stages.

Perform monthly skin self-checks for rashes, moles or other changes. If you notice any skin changes, schedule an appointment with a dermatologist.

Questions to ask include:

Mycosis fungoides is rare. Healthcare providers diagnose around 3,000 people with cutaneous T-cell lymphomas each year. On average, about 70% of all cutaneous T-cell lymphomas are mycosis fungoides. Because mycosis fungoides progresses slowly, more people may have the condition without knowing it.

Mycosis fungoides can affect people of all ages, but it’s most common in adults over 50. Males are twice as likely to develop mycosis fungoides. People who are Black are more likely to develop this condition than people who are white.

Advertisement

Mycosis fungoides occurs when T-cell lymphocytes become cancerous. When these cancerous T-cells circulate in your blood, they’re called Sézary cells.

Sézary syndrome occurs when you have large numbers of T-cells — called Sézary cells — in your blood that can go to your skin and lymph nodes.

Scientists haven’t identified a single cause that triggers mycosis fungoides. They’ve identified common changes in specific chromosomes, including missing genetic material and genetic material with errors, within the cancer cells. These changes develop over a person’s lifetime (acquired).

One of the challenges of diagnosing mycosis fungoides is that it doesn’t look the same on everyone. Also, in the early stages, it often resembles common skin conditions, like eczema and psoriasis.

Depending on the stage, it may look like a rash, raised and discolored skin or bumps that may develop sores. Most often, these skin changes occur on your body in places protected from sun exposure.

For many people, the first sign of mycosis fungoides is a skin rash that’s otherwise symptom-free. Although it’s a blood cancer, it’s easy to mistake for common skin conditions. This is why it’s so important to have a dermatologist check any skin changes. Early diagnosis and treatment can make all the difference regarding your prognosis. Many people who receive treatment early experience years with no symptoms.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic's health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability, and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic's health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability, and up-to-date clinical standards.

When you hear that you might have lymphoma, you want care from experts you can trust. At Cleveland Clinic, we craft a treatment plan tailored for you and your needs.