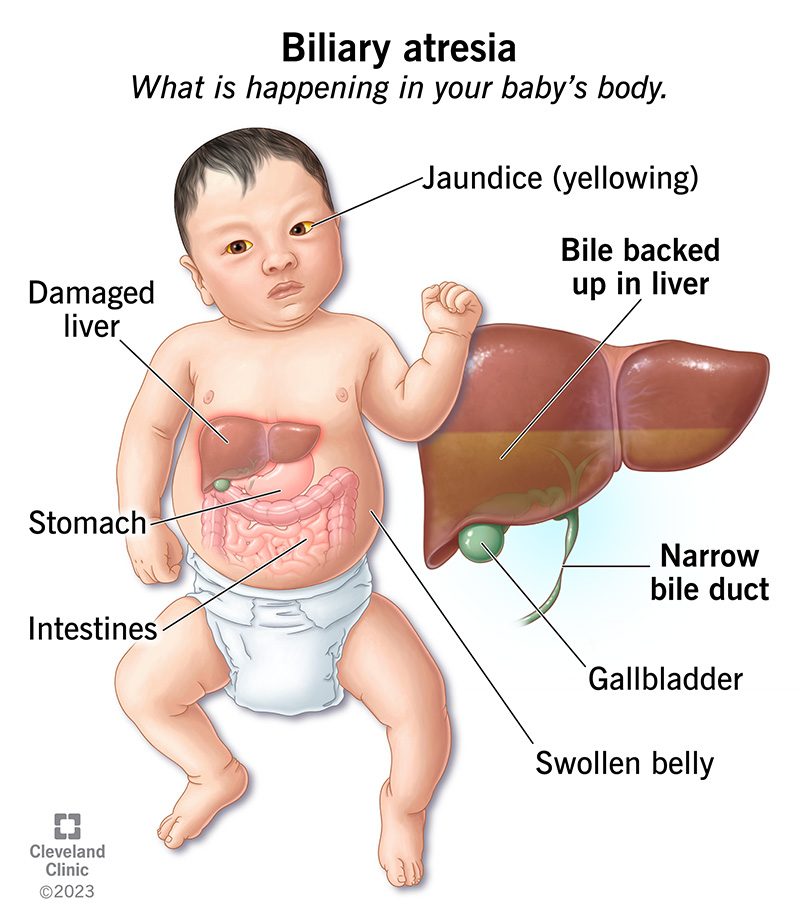

Biliary atresia is a condition that affects an infant’s liver. Bile normally flows from your baby’s liver to their small intestine. But with biliary atresia, your baby’s bile ducts (tubes that carry the bile) are blocked. So, bile builds up in their liver and damages it. Surgery improves bile flow, but most babies end up needing a liver transplant.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/21076-biliary-atresia)

Biliary atresia is a condition in which your baby’s bile ducts are blocked and can’t send bile from their liver to their small intestine. Bile is a substance your baby’s liver produces that carries waste products to their intestines. Bile also helps your baby’s intestines digest and absorb vital nutrients. Biliary atresia affects babies in their first few months of life and can quickly lead to severe liver damage without prompt treatment.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

A slowdown or stalling of bile flow (cholestasis) affects your baby’s liver and all the organs and tissues surrounding it. Bile clogs up in your baby’s liver and causes scarring that can prevent their liver from working normally. Also, their intestines can’t receive the bile needed to break down nutrients and support their growth.

Biliary atresia is a serious condition, but surgery can create a new path for bile to flow from your baby’s liver. This relieves symptoms and helps with digestion. However, due to liver damage, many babies with this condition ultimately need liver transplantation. The good news is that, thanks to medical advances, babies with biliary atresia often go on to enjoy a long and healthy life.

Researchers estimate that biliary atresia occurs in 1 in 12,000 babies born in the U.S. It’s more common in other areas of the world, such as Asia. For example, biliary atresia occurs in 1 in 6,000 babies born in Taiwan. Researchers continue to look into the reasons for these global differences.

Biliary atresia is the most common reason why babies and children need a liver transplant.

The first signs of biliary atresia usually appear a few weeks after birth and include:

Advertisement

These symptoms may develop by the time your baby is 6 to 10 weeks old:

The most obvious sign of biliary atresia is that your baby’s skin and the white parts of their eyes will appear yellow (jaundice). Jaundice is common in newborns and usually goes away after a week or two. But certain conditions like biliary atresia cause jaundice that lasts longer.

If your baby has jaundice beyond two weeks after birth, it’s important to take them to see a healthcare provider right away. It could be a sign of biliary atresia or another condition that needs treatment.

Babies with biliary atresia have poop that’s light beige or pale in color. Healthcare providers call these, “acholic stools.” The poop is too light because bile can’t reach their intestines. Bile gives poop its normal color, which is typically yellow, brown or green. Call your baby’s provider if you think your baby’s poop isn’t a normal color.

Researchers don’t fully understand why this condition occurs and continue to look into possible causes. Some theories suggest somatic genetic mutations may lead to abnormal development of fetal bile ducts. Somatic mutations are those that occur after conception and therefore aren’t passed down by one’s biological parents.

It can be frustrating to hear there’s no clear cause of your baby’s condition. But ongoing research may shed more light on the causes in the coming years.

Without treatment, biliary atresia can lead to:

These complications can lead to liver failure, which can be fatal. But there’s reason for hope. Spotting signs and symptoms early and taking your baby to get checked can lead to a diagnosis and life-saving treatment.

Healthcare providers diagnose biliary atresia through a physical exam and tests. If your baby has light-colored poop and/or jaundice that lasts longer than two weeks, take them for a checkup. Your baby’s provider will:

Advertisement

Your baby may need further tests to show how their bile ducts, liver and gall bladder are working. Possible tests include:

Your baby’s provider may also order additional tests to rule out conditions that have similar symptoms, such as Alagille syndrome. These tests may include genetic tests and newer inflammatory markers like MMP7.

This test is different than those listed above because healthcare providers often combine it with treatment.

A provider injects contrast dye into your baby’s gallbladder to provide detailed X-ray images of their bile ducts. How the dye moves or fails to move toward your baby’s small intestine shows the structure of their bile ducts and reveals blockages.

If the test confirms biliary atresia, surgeons can immediately begin addressing the problem. They create a new path for bile to flow out of your baby’s liver. This is called the Kasai procedure, and it’s typically the first treatment healthcare providers use to treat biliary atresia.

Healthcare providers can’t cure biliary atresia. But they can perform a surgery called the Kasai procedure that helps bile flow from your baby’s liver to their small intestine.

Advertisement

During the Kasai procedure, a surgeon removes blocked bile ducts. Then, they use part of your baby’s small intestine to create a new path for bile to flow out of their liver. This relieves the blockage and allows bile to flow normally again.

Soon after the Kasai procedure, your baby’s symptoms (like jaundice and abnormal poop color) will likely go away. Your baby’s intestines will be able to absorb nutrients more efficiently, which will support their growth.

However, this procedure usually isn’t a lifelong fix. Biliary atresia often causes damage to a baby’s liver that may slowly get worse. Many babies who have the Kasai procedure need a liver transplant sometime during childhood or their teenage years. Some need it sooner (before age 2) if bile blockages continue after the Kasai procedure.

The Kasai procedure helps babies regain normal bile flow, but the earlier it’s done, the better. Babies have the best chance of a successful Kasai procedure when it’s done within the first three months of life, especially within the first month.

Even after a successful Kasai procedure, many babies need a liver transplant later on (usually by their teenage years) due to liver scarring. Liver transplantation gives your child a very good chance at having a long and healthy life. Without any treatment, a baby may not live beyond one year.

Advertisement

Some babies with biliary atresia are born with other health issues like congenital heart defects or issues with their spleen. Your baby’s healthcare provider will tell you if there are other areas of concern. They’ll explain what these conditions mean for your baby’s treatment plan and future.

There’s no known way to prevent biliary atresia. While a genetic mutation may play a role in causing the condition, the mutation isn’t passed down from a baby’s biological parents. Nothing you do during pregnancy is known to cause this condition, and it’s not your fault if your baby develops it.

Your baby may need a little extra help getting enough calories and nutrients to support their growth. Bile usually travels to a baby’s small intestine to help with digestion, but biliary atresia disrupts that process. So, your baby may need special formulas or supplements to support their body’s needs and help them grow. Your baby’s provider will tell you if these are necessary and explain how to give them to your baby.

Biliary atresia can cause long-term liver damage. So, your baby will need medical care throughout their childhood. Even after a successful Kasai procedure, your baby may need a liver transplant. Having this possibility in the back of your mind can be stressful, but most babies who have a liver transplant thrive afterward.

If your baby receives a new liver, their provider will tell you how to care for them in the weeks, months and years afterward. For example, they’ll need to take medications to prevent their body from rejecting the new organ.

If your baby is at least two weeks old and has jaundice and/or pale poop, take them to see a healthcare provider. They’ll run tests to find the cause and give your baby appropriate treatment.

If your baby has biliary atresia, their provider will tell you how often to come in for appointments.

Some babies who have the Kasai procedure have continued blockages in their bile ducts and need further treatment. Once your baby is back home after the procedure, watch for the following symptoms and call their provider if they occur:

Learning your child has biliary atresia can feel confusing or overwhelming. Their provider will share lots of information with you, but it may be hard to sort it all out in the moment. It’s a good idea to bring a list of questions to each appointment and write down the answers your provider gives you. Some questions to get you started include:

Biliary atresia isn’t something that’s on most parents’ radars. Hearing the diagnosis can turn your whole world upside down. Treatment usually follows fast after the diagnosis, so you may not have a moment to even catch your breath.

It’s a lot to handle. Your baby’s healthcare team is there for you to offer guidance, resources and a path forward. There’s no question or concern that’s too small. Get the information you need to process what’s going on and learn how to care for your baby.

Don’t forget to take care of yourself, too. Lean on family and friends to help you prepare meals, watch your baby while you nap or simply be there to listen. Connecting with other parents who have children with biliary atresia can also help you and your family navigate this time.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

If your child has a problem with their liver, you want expert advice. Cleveland Clinic Children’s experts will create a personalized treatment plan for your child.