Primary biliary cholangitis is a chronic and progressive condition that causes inflammation and, eventually, the destruction of the bile ducts that run through your liver. Without working bile ducts, bile backs up in your liver, causing liver damage. This can lead to cirrhosis of the liver. But medication can delay and sometimes prevent it.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/Images/org/health/articles/17715-primary-biliary-cholangitis)

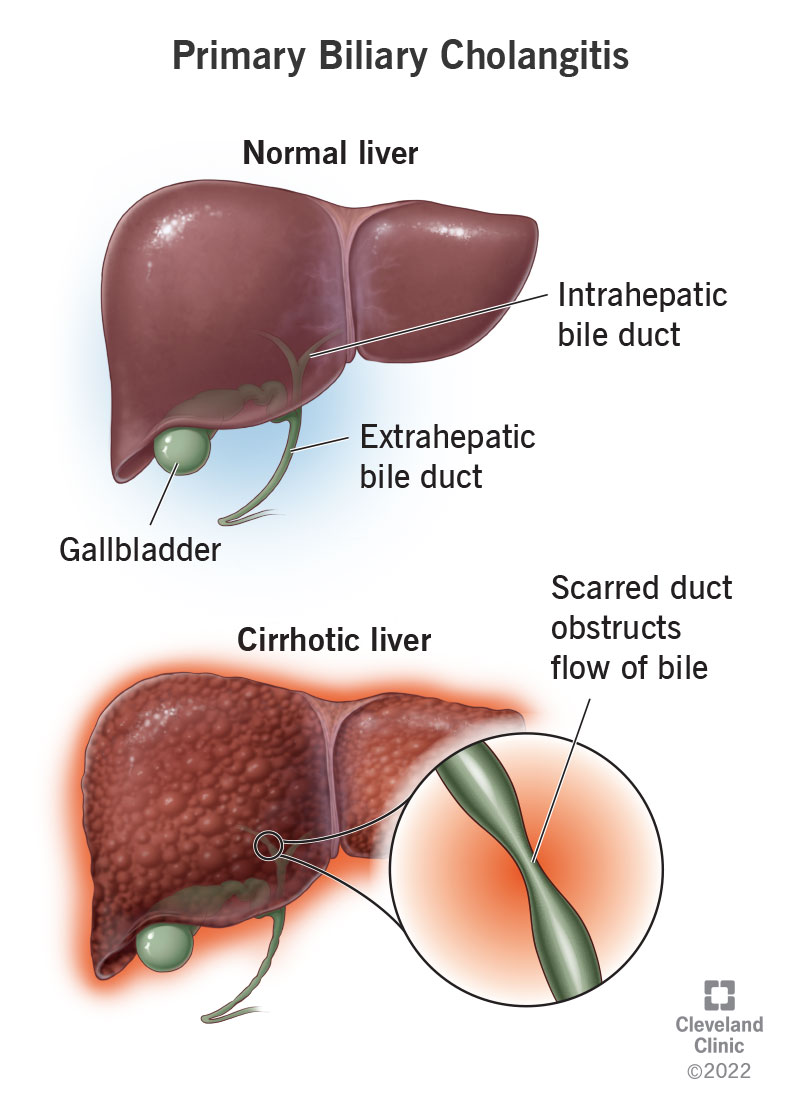

Primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) is a liver disease that affects the bile ducts that run through your liver. It slowly degrades those bile ducts, making it harder for bile to flow through. Bile backs up inside your liver, which damages the tissues. Scar tissue gradually replaces healthy tissue and your liver gradually loses its functionality. This is known as cirrhosis. PBC was formerly known as primary biliary cirrhosis.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

“Cholangitis” means inflammation in your bile ducts. “Biliary” means of the bile ducts, and “primary” means original. This means that the disease itself is the original cause of inflammation in your bile ducts. There isn’t some other condition causing inflammation, such as an infection or a blockage. Since the inflammation isn’t responding to anything in particular, it doesn’t know when to stop.

Chronic inflammation degrades your body’s tissues over time. While temporary inflammation can be part of the normal healing process, constant inflammation causes overactive healing in the form of scarring. When your bile ducts are scarred, they become narrowed and distorted, which obstructs the flow of bile. Bile backs up into your liver, causing inflammation and eventually, scarring (cirrhosis).

Primary biliary cholangitis is a chronic and progressive condition, which means it doesn’t go away and can get worse over time. It progresses slowly through several stages. At the beginning, you might not notice it at all. But in the end, it can cause liver failure, which is fatal without a liver transplant. Fortunately, medication helps slow the progress of the disease, and not everyone will reach this stage.

Advertisement

The two conditions are very similar. One major difference is that primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) affects only your intrahepatic bile ducts, the bile ducts within your liver. Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) affects all of your bile ducts, including your extrahepatic ducts. The two conditions also tend to affect different populations. And while you can treat PBC with medication, PSC has no effective treatment.

It primarily affects females, by a ratio of 10-to-1. In the U.S., it affects around 60 females per 100,000 and 15 males per 100,000. Most are diagnosed after the age of 40. It’s more common in Scotland, Scandinavia and Northeast England. It’s also more common in people with a personal or family history of autoimmune disease, suggesting it might be a partly genetic disorder.

Many people with PBC have no symptoms in the early stages. As the disease progresses, signs of biliary disease begin to appear. The earliest and most common symptoms of people with PBC are:

These symptoms affect different people to different degrees. They can occur later or earlier in the course of your disease, and they can be mild to severe at any stage. How your symptoms present doesn’t seem to be related to how advanced your disease is. However, some research has suggested that more severe symptoms earlier on may predict a faster progression overall.

You may not notice biliary disease in the early stages. But as it progresses, complications can begin to develop. Bile that can’t flow will begin to leak into your bloodstream, causing illness. Bile that can’t flow also can’t reach your digestive system, where it’s needed to aid digestion. In later stages, scar tissue in your liver begins to affect the blood vessels that pass through it, causing portal hypertension.

When your digestive system lacks the bile it needs, it has trouble breaking down and absorbing fats. Fat malabsorption can cause:

When scar tissue in your liver begins to obstruct the blood vessels that run through it, it causes portal hypertension — high blood pressure in those veins and the veins that branch off from them. Portal hypertension can lead to:

Advertisement

In PBC, it appears that your own immune system attacks the cells lining your intrahepatic bile ducts, causing inflammation. It’s as if your immune system mistakes these cells for foreign invaders. This is called autoimmune disease. Your immune system acts automatically to destroy healthy cells without any apparent reason, or any regulation telling it when to stop. Chronic inflammation leads to scarring.

We don’t know why autoimmune disease occurs. There does appear to be a genetic factor. People who get autoimmune diseases often have a family history of autoimmune diseases, and they often get more than one type. There also seems to be an environmental factor, meaning that it may take something in your environment to trigger the disease. It may be a chemical or infection that you’re exposed to.

Your healthcare provider will ask about your medical history and symptoms and physically examine you. Then they’ll test a sample of your blood for evidence of PBC. They look for particular antibodies in your blood that are associated with PBC, especially one called antimitochondrial antibody (AMA). They also look for elevated liver enzymes that indicate liver stress, especially alkaline phosphatase.

Advertisement

If your test results are positive for PBC, your provider will want to look at images of your liver and biliary system next. This helps to rule out other possible causes of your symptoms, and can also help show how advanced the disease is. They’ll usually begin with a simple test like an abdominal ultrasound. But sometimes, they may need to take clearer images with some type of MRI (magnetic resonance imaging).

About 5% of people with PBC test negative for AMA but have other signs and symptoms. In this case, your provider may need to take a liver biopsy to confirm you have PBC. They can usually do this as a bedside procedure using a needle inserted into your liver. The needle will withdraw a tiny tissue sample, and your provider will send the sample to a lab for examination under a microscope.

Providers use the following treatments for primary biliary cholangitis:

There’s no cure for PBC, but you can slow it down and improve your condition with medication. Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) is a type of bile salt that can help clear bile from your liver and reduce liver damage. It works well for about half of people with PBC, especially in the early stages. For those who don’t benefit from UDCA, doctors sometimes recommend a different bile salt called obeticholic acid (Ocaliva®). Your doctor may also suggest newer medications, like seladelpar (Livdelzi®) and elafibrinor (Iqirvo®).

Advertisement

Doctors can also treat some of your individual symptoms with different medications. For itching, they may recommend antihistamines such as diphenhydramine (Benadryl® or Aler-Dryl®), ultraviolet light therapy or bile acid sequestrants such as cholestyramine. Vitamin supplements can help prevent vitamin deficiencies and side effects such as osteoporosis. Some people with fatigue benefit from stimulants such as modafinil.

If medication doesn’t improve your condition and your liver function continues to decline, your doctor may put you on the liver transplant waiting list. Liver transplant surgery has excellent results for people with PBC. Although, like other autoimmune diseases, PBC may return after your liver transplant, but it tends to progress much more slowly the second time around. Life expectancy after your transplant is normal.

In most cases, primary biliary cholangitis progresses slowly. With earlier diagnosis and treatment, you can often prevent or at least delay the later stages and complications of the disease. Many people are able to effectively control their symptoms with medications, although fatigue in PBC continues to be difficult to treat. Many people live for years without too much interference from PBC in their daily lives.

However, not everyone discovers PBC in time to treat it in the early stages. And some people simply have a more aggressive form of the disease. Higher levels of fatigue and higher levels of bilirubin in your blood predict a faster progression to liver failure. If you reach this stage, you’ll need a liver transplant to survive. But for those with PBC who have successful liver transplants, the prognosis is excellent.

It takes an average of 15 to 20 years for PBC to progress to the terminal stage. The first stage, when you test positive for PBC but you don’t yet have symptoms, can last a long time. About half of people will begin having symptoms in the next five to 10 years. Once you have symptoms, the average life expectancy is about 10 years. For those who have successful liver transplants, the 10-year survival rate is 65%.

A healthy diet and lifestyle can help you keep your liver as healthy as possible for as long as possible.

For example:

Many people with primary biliary cholangitis can live for years without it affecting their lives. But, regardless, having a progressive and potentially terminal disease can weigh on you. Make sure you talk to your healthcare provider about ways to ease your physical, mental and emotional stress, including support networks for people living with PBC. Remember, your overall health is much bigger than this condition alone.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic providers compassionately diagnose and treat all liver diseases using advanced therapies backed by the latest research.