Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome is when you have an extra electrical pathway in your heart that lets signals travel too fast. This can lead to abnormal heartbeats and symptoms like a racing or pounding heart. Rarely, WPW syndrome leads to sudden cardiac death. A procedure to get rid of this extra pathway cures the problem in most people.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/17643-wolff-parkinson-white-syndrome)

Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome is a condition where you have an extra electrical pathway for signals to move through your heart. Having this pathway makes you more likely to develop an abnormal heartbeat like supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) or atrial fibrillation (AFib). Treatment can manage symptoms of these arrhythmias and lower your risk for complications.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

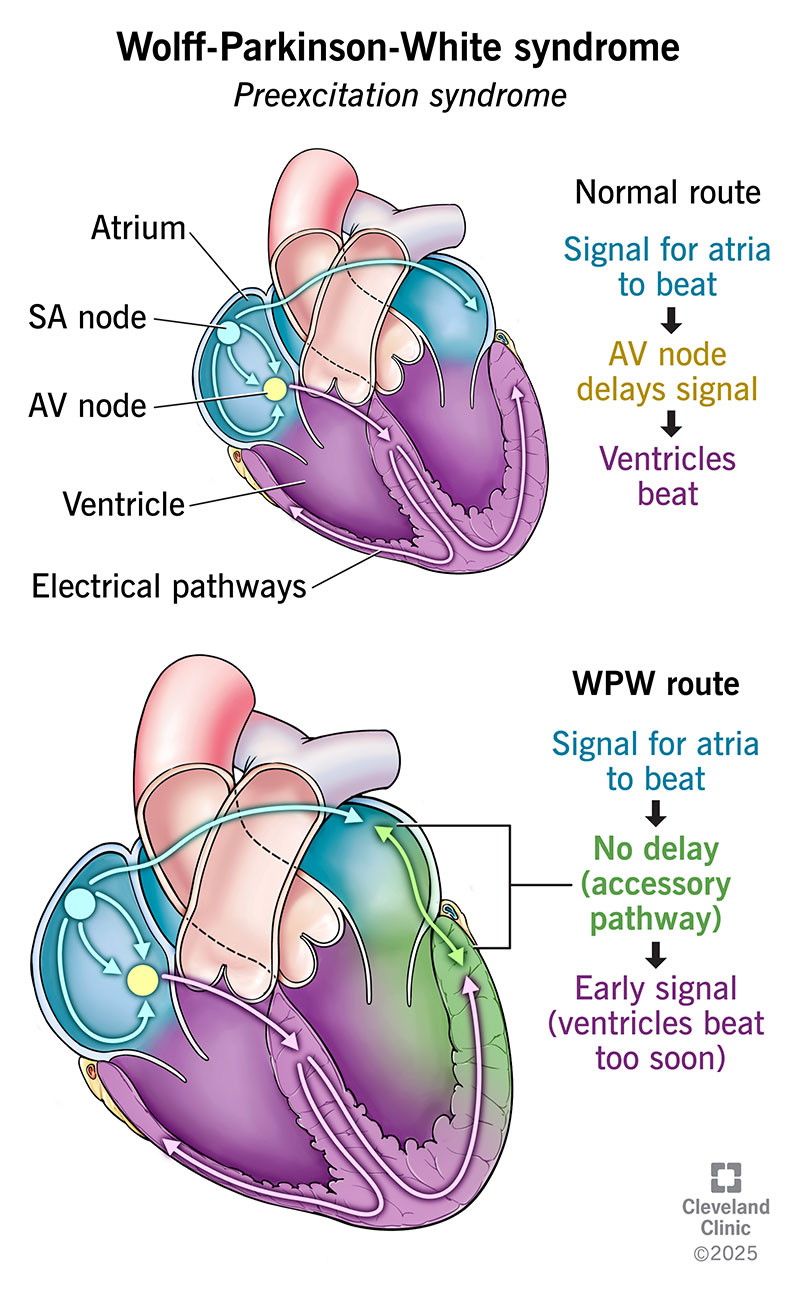

Normally, signals take a predictable route through your heart to control your heart rate and rhythm. But with WPW syndrome, you’re born with one or more extra or “accessory” pathways that take signals on a different route — a bit like a shortcut. This makes the signals reach your heart’s lower chambers (ventricles) too soon.

As a result, your ventricles contract sooner than they should. This is called preexcitation. And it’s why you might also hear WPW syndrome called a preexcitation syndrome. Normally, your ventricles have to wait for signals to travel their usual route — including through an area called the AV node that slows them down a bit. The extra pathway detours around the AV node. So, signals travel through your heart too quickly.

WPW syndrome affects 1 to 3 in every 1,000 people in the U.S. It’s more common among people with a heart defect called Ebstein’s anomaly. About 100 to 340 in every 1,000 people with Ebstein’s anomaly are also born with WPW syndrome.

WPW syndrome may cause symptoms like:

Advertisement

Symptoms develop when your heart beats too fast or out of rhythm. There’s not enough time for blood to fill your heart’s chambers before the next heartbeat. This means your heart can’t send as much blood to your body as it should.

For most people with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, the cause is unknown. But changes to the PRKAG2 gene are one known cause for a small number of people. These gene changes can pass down within biological families.

Without treatment, WPW syndrome may lead to:

Healthcare providers usually diagnose WPW syndrome with an electrocardiogram (ECG/EKG). Your provider can see visible heartbeat differences in a Wolff-Parkinson-White EKG compared to a normal EKG. For example, they can see signs of your ventricles contracting too soon (preexcitation).

Your provider will diagnose you with “WPW pattern” if they see signs of an accessory pathway on your EKG. You have WPW syndrome if there’s the telltale pattern on your EKG, plus you develop symptoms of an abnormal heartbeat.

Other tests you may need include:

These tests tell your provider more about your heart rate, rhythm and electrical activity. The results help your provider understand your risk for serious issues and plan treatment.

Most people with WPW syndrome receive a diagnosis between the ages of 10 and 30.

Treatment for WPW syndrome includes medicines and procedures. These manage symptoms, prevent abnormal heartbeats and lower your risk for sudden cardiac death. Your provider will suggest treatments based on your symptom history and test results. You may need one or more of the following:

Advertisement

You need routine follow-up appointments to manage WPW syndrome. Your provider will tell you how often to come in. Contact your provider anytime you have new or changing symptoms.

Seeking care for your mental health is also important. WPW syndrome affects your heart, but it can also affect your emotions and state of mind. It’s common to feel anxious, depressed or scared of dying. Speaking with a counselor can help you work through these emotions and feel better from day to day.

Seek emergency care if you:

Someone else may need to call for help if you pass out. Tell your loved ones and anyone you regularly spend time with about your condition. Make sure they know when they should call emergency services for you.

Most people who receive treatment for Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome have a typical life expectancy. Ablation can cure WPW syndrome in many cases and protect you from sudden cardiac death. Your provider can tell you more about what to expect in your situation.

Your provider will also talk to you about how to manage this condition in your daily life. For example, you may need to avoid things that trigger an abnormal heartbeat, like:

Advertisement

Eating in heart-healthy ways can help your heart. Physical activity is also important. Ask your provider which types of exercise are safe for you.

If your child has Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, you might worry about their heart. You may also have lots of questions about what’s unsafe for them. It’s important to talk to your child’s provider to learn more about any restrictions.

For example, their provider can advise you on whether it’s safe for your child to play sports. And they’ll explain what your child should do if they have a rapid heartbeat while at school. They’ll also help you talk about WPW syndrome to your child in ways they can understand.

Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome might feel like a scary diagnosis. But healthcare providers are prepared to ease your worries and protect your heart. The chances are good that treatment can manage or even cure this condition. Don’t hesitate to ask any questions that come to your mind. Your providers are there to help you feel supported and more confident in the road ahead.

Advertisement

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

A too-fast heart beat can take the fun out of being a kid. Cleveland Clinic Children’s cardiology providers can treat your child’s Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome.