An anal fistula is usually a side effect of an anal abscess, an infected wound that drains pus from your anus. The draining abscess can create a tunnel through your anus to the skin outside. Anal pain, swelling and redness are the primary symptoms. Surgery is the primary treatment.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/Images/org/health/articles/14466-anal-fistula)

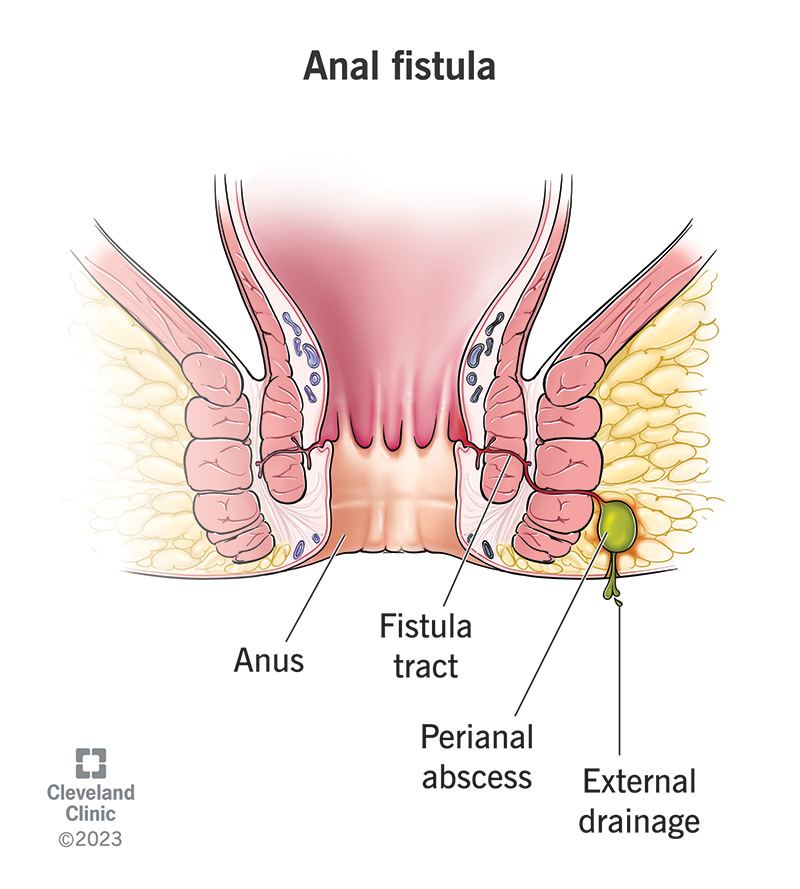

An anal fistula is an abnormal passageway that develops from inside your anus to the skin outside. It usually develops in the upper part of your anus (butthole), where your anal glands are. When these glands become infected, drainage from the infection can create a fistula. This infection is called a perianal abscess. (Sometimes an anal fistula is also called a perianal fistula. “Perianal” means in the region of your anus.)

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

A fistula is a relatively common anorectal condition. It’s twice as common in males. About half of people who get an infected anal gland will develop a fistula. An infected gland that forms an abscess, a pocket of pus that needs to drain, causes 75% of anal fistulas.

Video content: This video is available to watch online.

View video online (https://cdnapisec.kaltura.com/p/2207941/sp/220794100/playManifest/entryId/1_bl79f9tu/flavorId/1_5f3sgelj/format/url/protocol/https/a.mp4)

Learn the difference between an anal fissure and an anal fistula.

The most common anal fistula symptoms are:

Less common symptoms include:

You may or may not be able to see the fistula with a mirror.

An anal fistula looks like a hole in the skin near your anus. The hole is actually the outermost portion of the tunnel, which connects to the abscess inside. It might ooze drainage, like pus, blood or poop, especially when you touch the skin around it. Some older fistulas may close at the opening, while the rest of the tunnel remains. This causes pain and swelling until the fistula reopens to let out the drainage.

Advertisement

Fistulas can occur throughout your body, either between different organs or from an organ to an opening in your skin. They usually occur when your tissues are inflamed for a long time, due to an injury or disease. Chronic inflammation and infection can eventually erode into the nearby tissues, especially when pus needs to drain. This can create a channel between the wound and nearby tissues.

The most common cause of an anal fistula is a perianal abscess, which usually forms over an infected anal gland. An abscess is a pocket of pus that develops at the site of an infection. The pus needs to drain away and may create its own drainage channel to the outside. Sometimes, a healthcare provider creates a drainage channel to treat the abscess. But often, the wound doesn’t heal completely, leaving a fistula. Uncommon causes of anal fistulas include:

You’re more likely to get an anal fistula if you:

A fistula that goes untreated generally won’t heal on its own. This can lead to long-term complications, such as:

Healthcare providers can find most anal fistulas during a physical exam, but sometimes the opening to the outside is closed. Your provider will also want to find the inside opening to the fistula, within your anus. This part might require anesthesia. If it hurts too much for your provider to touch or open your anus to examine the inside, they may have to examine you in the operating room under sedation.

Advertisement

To find the inside source of the fistula, your provider may use a lighted scope, like an anoscope or proctoscope (a longer scope that can visualize your rectum). Sometimes, they’ll inject hydrogen peroxide into the external opening to find the infection at the source of the fistula. The peroxide will interact with the infection and create bubbles or foam at the site. Finding the inside source can confirm the fistula.

Your healthcare provider might need to take imaging tests (radiology) to see the path of your fistula. This might mean:

Your provider needs to know the pathway of your fistula in order to determine how to treat it. They’ll classify your fistula by its pathway.

Advertisement

Healthcare providers classify anal fistulas by where they’re located in relation to your anal sphincter muscles. These are the muscles that control your bowel movements, so it’s important to protect them. Your provider might refer to your anal fistula by a specific name based on its location, such as:

You don’t have to know or remember what type of anal fistula you have, but the type will influence how your provider treats it. If it involves much of your sphincter muscles, the treatment might be more complicated. They have to be careful not to injure these muscles when they fix your anal fistula.

Advertisement

Most anal fistulas will require surgery to fix. Spontaneous healing is usually followed by recurring infections and abscesses that reopen the fistula. However, if your fistula is caused by inflammatory bowel disease and isn’t infected, it’ll occasionally heal with medical treatment. Your provider might try treatment with an immunomodulator, like infliximab, before resorting to surgery for these fistulas.

Anal fistula surgery can be simple or complex, depending on how simple or complex the fistula is. The most common anal fistulas are simple, intersphincteric fistulas, which only involve a small amount of muscle. These are safe to treat in a single operation. More complex fistulas may need surgery in stages.

If your anal fistula involves only a minimal amount of muscle and doesn’t have any branches, it’s considered a simple fistula. The surgical treatment for a simple fistula is called a fistulotomy. This one-and-done procedure is the easiest and the most effective way to treat an anal fistula (about 95%).

Fistulotomy: Your colorectal surgeon will cut through the roof of the fistula, allowing it to fill in from the bottom up. They might also remove infected tissue. Cutting through the roof may mean cutting through a small amount of muscle, but a little is OK. Cutting too much muscle risks damaging your bowel control.

Your fistula is considered complex if it involves a significant amount of muscle, if it has branches or if you have preexisting conditions that raise your risk of complications from surgery. Complex fistulas may require multiple surgeries to fix. Your colorectal surgeon may use one or more of these techniques:

The main risks are:

Anal fistula procedures are generally outpatient procedures, so you can go home the same day, although some people will need to return for more surgery later. You’ll have prescription pain medication to take home with you, along with some instructions for self-care. These may include:

Your outlook will depend on how simple or complex your anal fistula is. This determines how extensive the treatment and recovery process will be. In general, you can expect to spend three to six weeks recovering from one or several surgeries. Some fistulas return after surgery, especially if they had many branches or they were caused by a chronic condition. Some people with IBD get multiple anal fistulas.

Always see a healthcare provider about anal pain. Anorectal conditions that cause significant pain may be serious. Don’t assume it’s something that will go away by itself. Hemorrhoids may be more common and familiar, but they aren’t usually very painful. If a general (primary care) practitioner tells you it’s a hemorrhoid but the pain continues, see a specialist, like a gastroenterologist or colorectal surgeon.

A perianal vaginal fistula is usually called a rectovaginal fistula, because it usually connects from your rectum to your vagina. Your rectum is the part of your large intestine that comes just before your anus. The border between your rectum and vagina is much narrower than between your vagina and anus. A vaginal fistula can develop from any part of your intestines, but it’s usually from your rectum or colon.

An anal fissure is a split or tear in the lining of your anal canal. It can cause similar symptoms to an anal fistula, but a fissure is a superficial wound. It doesn’t tunnel through your anal wall to your skin the way a fistula does. However, it’s possible that an anal fissure could develop into an anal fistula. If an anal fissure becomes infected, it could form an abscess, which could create an anal fistula when it drains.

Severe anal pain can be both physically and psychologically debilitating. Not only does it haunt you every time you sit or visit the toilet, but it may feel like a difficult thing to discuss with a healthcare provider. Don’t let this stop you. Anorectal diseases and conditions deserve the same attention as any other. An anal fistula needs treatment, and the sooner you get it, the simpler that treatment is likely to be.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

If you have issues with your digestive system, you need a team of experts you can trust. Our gastroenterology specialists at Cleveland Clinic can help.