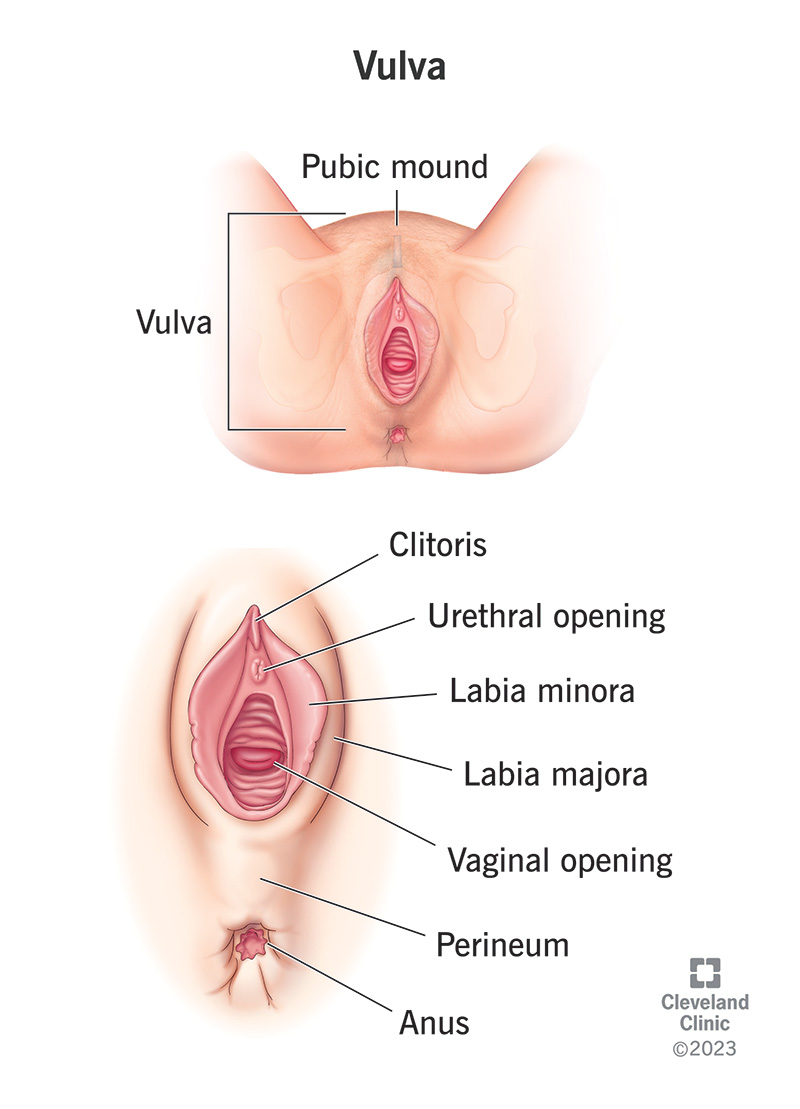

Your vulva consists of many parts that are essential to your reproductive and sexual health like your inner and outer labia, clitoris, vaginal opening and urethral opening. Avoiding irritants and taking steps to prevent infections, including STIs, can keep your vulva healthy.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/vulva)

Your vulva is another name for your genitals. It’s the area between your legs that allows you to menstruate, give birth, pee and experience sexual pleasure. Although vulvas are an essential part of female anatomy, many people don’t even know the word. Instead, they use “vagina” as a catch-all for all the pleasure-producing parts related to female reproductive anatomy.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

But your vulva includes so much more than your vagina. Understanding your vulva can improve your sex life and your overall health.

“Vulva” is derived from a Latin word meaning “covering.” Your vulva houses key internal reproductive organs, protecting them from injury. But your vulva does more than provide cover. It’s essential in its own right.

Your vulva plays a role in:

The word “genitals” refers primarily to your external sex organs, what you’d see if you used a handheld mirror to take a look at what’s between your legs. But when it comes to your vulva, the anatomy isn’t so straightforward. For example, you can look into a standing mirror straight on and see the V-shaped patch of skin called your pubic mound or “mons.”

Advertisement

Also, what you see when you look at your vulva through that imaginary handheld mirror depends on processes inside your body, too. Here are the key parts of your vulva to know about and where they’re located.

Your mons is named after Venus, the Roman goddess of love, beauty and fertility. This is the plump V-shaped patch of skin that extends from the top of your pelvic bone to where your thighs meet. From puberty onwards, pubic hair grows on your mons.

Your mons absorbs impact during penetration. For some people, pressure on the mons during arousal can stimulate sensitive tissue, causing pleasurable sensations. Others might not feel anything or might experience painful sensations.

Pubic hair also grows on your outer lips. These two vertical “lips” are actually plump skin folds that encase the innermost parts of your vulva. They’re filled with erectile tissue that becomes engorged (filled with blood) when you’re aroused. They come in different shapes and sizes for everyone.

Your inner lips are hairless, vertical “lips” inside your outer lips. They start above your clitoris and extend downward to the patch of skin between your vaginal opening and anus (perineum). Some people refer to the uppermost part as the “clitoral hood.” It houses and protects your highly sensitive clitoris. It can diffuse some of the sensation from your clitoris so that clitoral stimulation feels pleasurable instead of painful during sex.

Like your outer lips, inner lips come in many varieties. Some are symmetrical. Others aren’t. Some are tucked inside the outer lips, while others stick out and hang down. Like your outer lips, your inner lips are highly sensitive and fill with blood when you’re aroused.

A roughly pea-sized portion of your clitoris called the glans is underneath your clitoral hood. Your clitoris is the pleasure center of your anatomy. According to a recent study, it contains more than 10,000 nerve endings — more than any other part of the human body. Most people with a clitoris require direct or indirect clitoral stimulation to experience orgasm. Still, the clitoris is so sensitive that too much pressure (or even touching it directly) feels painful for some people.

If you hold the glans between your thumb and pointer finger, you can feel the shaft of your clitoris. This part extends into your body and connects to the internal parts of your clitoris.

Just below your clit is the urethral opening. This is where pee exits your body via your urethra, the tube that carries pee from your bladder.

Important structures associated with your urethral opening include Skene’s glands. They’re also called “the female prostate” because they produce a milky substance similar to ejaculate in males. This substance lubricates your urethral opening when you pee, preventing urinary tract infections (UTIs).

Advertisement

Your urethral sponge (spongy tissue surrounding your urethra) is another important structure to know about. Pressure on the part of your urethral sponge near the front of your vaginal wall inside your vagina feels pleasurable to some people. This area is sometimes called the “G-spot.” In some people, stimulating this area can cause Skene’s glands to release the milky fluid. The release is more commonly called “squirting.”

Your vaginal opening is below your urethral opening. Your vagina is a flexible, muscular canal inside your body that allows you to menstruate, become pregnant and give birth. The outermost one-third of your vagina (the portion commonly associated with your vulva) is filled with highly sensitive nerve endings that usually produce pleasurable feelings when touched.

Other important related structures may include a hymen, a delicate membrane that sits over part of your vaginal opening. It can tear during your first experience with penetration like a tampon or sex, or even from some exercises.

Your Bartholin glands are also important. They’re located at the entrance of your vagina and secrete fluid that helps keep your vagina lubricated. The lubrication makes contact with your vagina and vulva feel more pleasurable than painful during sex. But Bartholin glands don’t do all the work. Skene’s glands and secretions from your vaginal wall also keep you lubricated.

Advertisement

Infections and skin conditions are the most common conditions that affect your vulva. Given your vulva’s role in helping you pee and have sex, it’s a given that common conditions include urinary tract infections and sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

Advertisement

All vulvas generally have the same parts. Still, no two vulvas are the same. This is why it’s so important to familiarize yourself with your vulva, so you recognize changes that may signal a condition. Get to know how your vulva typically looks and smells. Pay attention to the fluids your vagina secretes at various points during your menstrual cycle. Familiarize yourself with the sensations you feel when using your vulva — peeing, menstruating or having sex — so you know what’s typical for you.

Changes signaling a condition affecting your vulva may involve your:

Changes to your vulva are common during menopause, the period in life when you stop getting your periods. During menopause, estrogen levels drop. The decrease can lead to vaginal dryness and thinning pubic hair. You may notice less fatty tissue in your vulva and experience pain during or after penetrative sex.

Talk to your provider if you’re noticing changes in your vulva. You don’t have to live with discomfort or feel embarrassed. There are treatments and lifestyle changes that can help.

You can prevent many of the conditions that affect your vulva by keeping your vulva clean, dry and free from irritants. Since irritation and infection often involve your vagina, too, good vulvar care also keeps your vagina healthy.

To care for your vulva:

Protecting yourself from STIs is an essential part of caring for your vulva. Learn about how various STIs spread. For example, some STIs, like HPV, spread through skin-to-skin contact. Other STIs — like chlamydia and gonorrhea — spread through body fluids, including vaginal fluid and semen. Understanding how various STIs spread can shape how you practice safer sex in the bedroom and protect your vulva.

Speak to your healthcare provider about safer sex practices.

One of the best things you can do for your health is to familiarize yourself with your vulva. This includes understanding how it works to maintain your reproductive and sexual health. Too often, sexual anatomy gets reduced to only those parts responsible for reproduction: vaginas, uteruses, fallopian tubes and ovaries. But your vulva has a key role to play in both reproduction and your well-being as a healthy, sexual human being. Care for your vulva with the same attention you’d direct toward any essential part of your anatomy.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

From routine pelvic exams to high-risk pregnancies, Cleveland Clinic’s Ob/Gyns are here for you at any point in life.