Gliding past mid-court, 14-year-old Myles Grimmett dribbles to his left, past a defender, and then pulls up behind the three-point line to smoothly sink a lefthanded jump shot.

Watching that basketball highlight on a computer in his Cleveland Clinic office, orthopaedic surgeon and Section Head of Orthopaedic Oncology Nathan Mesko, MD, marvels at Myles’ precision and athleticism. Myles is his longtime patient and a starting guard on the Elyria High School freshman team.

“It’s incredible what he’s been able to do. If you’d asked me when he was 5 years old what was possible for him, I couldn’t imagine what he’s doing today,” says Dr. Mesko, who collaborated with plastic surgeon Graham Schwarz, MD, and Cleveland Clinic Children’s pediatric oncologist Peter Anderson, MD, to treat Myles for a form of bone cancer nearly 10 years ago.

After 5-year-old Myles was diagnosed with osteosarcoma just below the shoulder in his right humerus, the upper arm bone, his medical team at Cleveland Clinic faced a challenge. Do they amputate the arm, which had once been common practice when a large tumor infiltrates the bone? Or do they – as Dr. Mesko describes it – “get creative?”

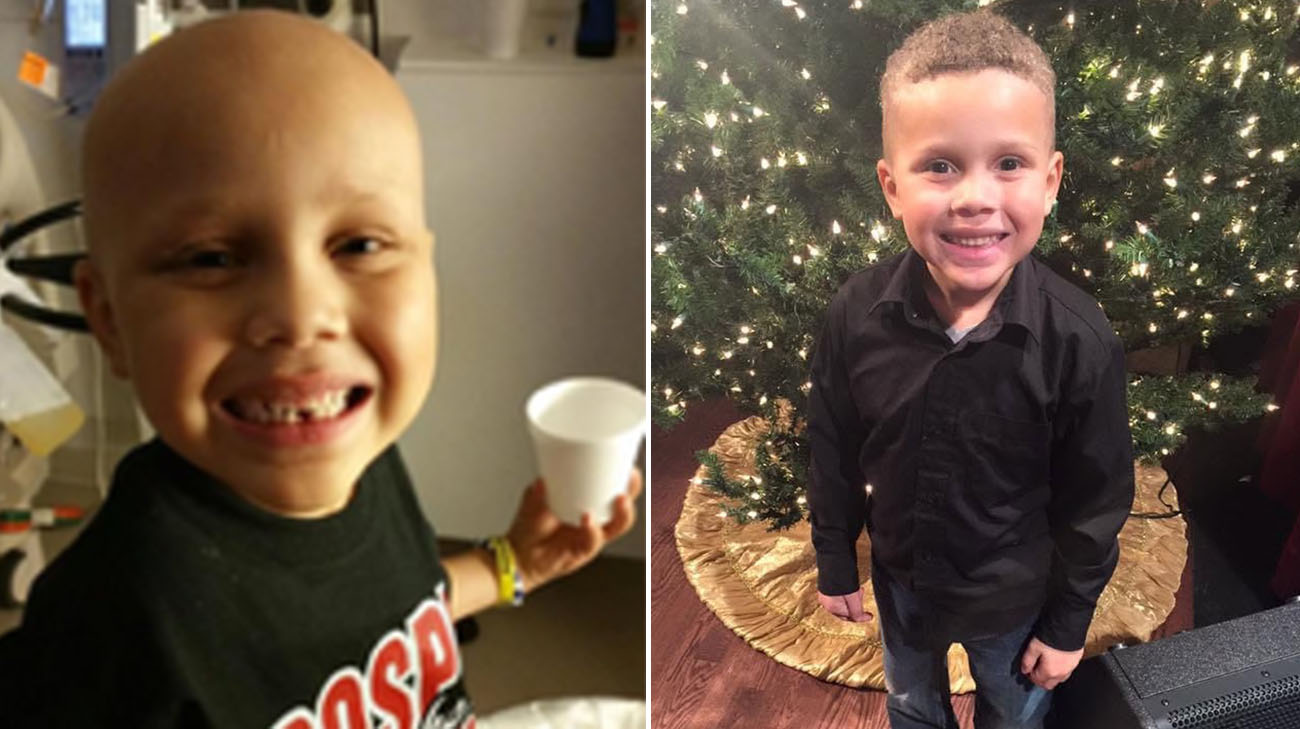

After receiving his diagnosis, Myles underwent chemotherapy followed by surgery. (Courtesy: Brittney Atkinson)

They chose the latter, undertaking the free fibula transplant technique to reconstruct and restore the function of Myles’ arm.

After excising the tumor and surrounding bone from Myles’ arm, they replaced it by removing 80% of the non-weight-bearing fibula in Myles’ left leg (leaving only the portion that attaches to the ankle joint), parsing out a small section near the upper end of the fibula that matched the size of the diseased humerus, and then attaching a plate with screws to connect that bone, with blood vessels and nerves intact, into his arm. The expectation was it would restore his functionality.

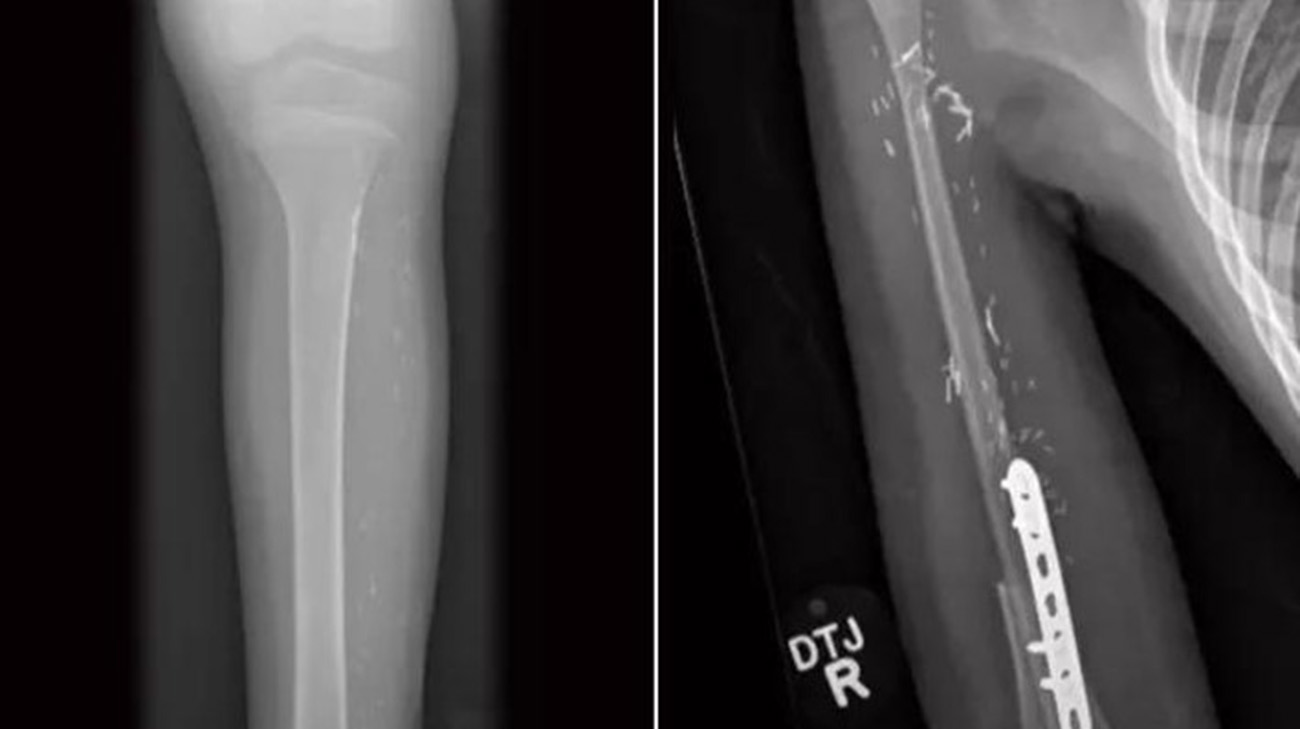

Surgeons removed the diseased bone in Myles’ arm and replaced it with a section of his fibula, shaping it to fit and securing it with a plate and screws while keeping its blood supply intact. (Courtesy: Cleveland Clinic)

“The fibula is one of the redundant features we have in the body, so, we can ‘borrow’ it, as we did for Myles,” explains Dr. Mesko.

An active youngster, who enjoyed playing with older brother Rondell, Myles complained of pain in his shoulder one day when his mom, Brittney, picked him up from pre-school. She iced it and says she didn’t think much about it. “I told him you’ll be fine tomorrow.”

Scans of Myles' fibula (left) and reconstructed humerus (right). (Courtesy: Cleveland Clinic)

But the next day, Myles again complained about the pain in his right shoulder, which by then had gotten swollen. Myles thought his muscle was growing in a Popeye-like fashion. But a visit to his pediatrician, who took an X-ray of his arm, indicated otherwise.

“We left the office and hadn’t made it to the end of the parking lot when the doctor called and told me to go home, pack a bag and bring Myles back,” recalls Brittney . “I was freaking out!”

Hours later, Myles was admitted to Cleveland Clinic Children’s with Brittney and Myles’s dad Rondell Sr. by his side. Within a few days, he began 30 weeks of intense chemotherapy, a common approach in treating sarcoma to shrink the tumor before surgical removal. During that time, Drs. Mesko, Schwarz and Anderson devised the intricate plan that would guide the surgical procedure to not only save his life but enable him to retain nearly all functionality.

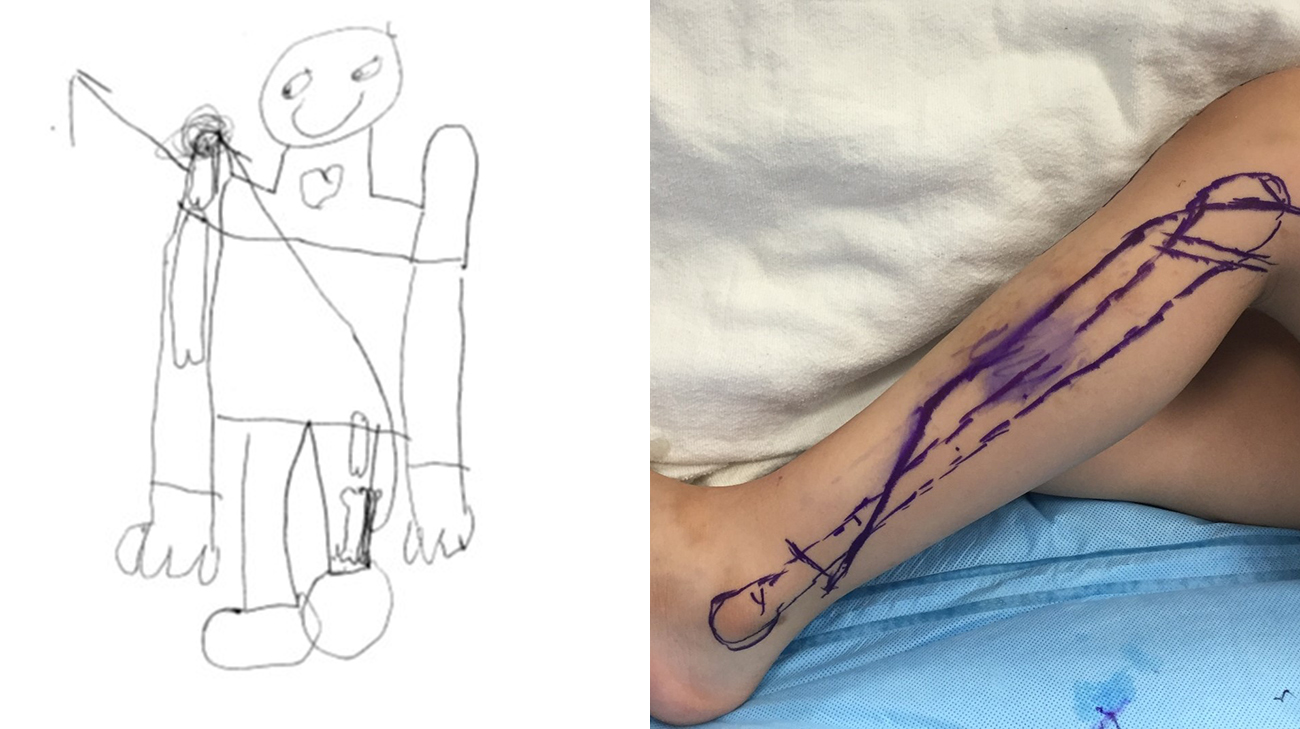

When he was 5 years old, Myles sketched a drawing for Dr. Mesko that showed the journey his fibula made to repair his arm. Dr. Mesko keeps the drawing on his office wall. (left) The markings on Myles' leg are part of preoperative planning. They serve as vital guides for the surgical team. (right) (Courtesy: Cleveland Clinic)

Nine years later, Myles’ recollection of that time is somewhat hazy. He states, “I have some good and bad memories, but I wasn’t really scared. I just knew I was sick.”

Surgeons performed the successful surgery soon after Myles turned 6. More chemotherapy followed the operation. Three months later, while still wearing casts on his arm and leg, Myles suffered a setback at a family reunion.

“Someone ran into the bathroom screaming ‘Myles broke his arm’,” states Brittney. Myles fell while wrestling with cousins.

Myles celebrating five years of remission. (Courtesy: Brittney Atkinson)

Fortunately, the break in Myles’ reconstructed arm was clean and healed robustly. Even with more months added to his time in a cast and sling, Myles didn’t slow down. Eager to keep up with his brother and friends, in sports and other activities, he began using his non-dominant left hand. As the years passed, his newfound ambidexterity transferred to the courts, as he primarily dribbles and shoots the basketball with his left arm.

“I can shoot floaters and layups with my right hand, and I still use it to write with a pen,” Myles explains. “But it’s just easier with my left.”

Myles continues staying active while playing his favorite sport. (Courtesy: Cleveland Clinic)

Also, other than occasional numbness below his ankle, his left leg also functions normally. That means Myles – who also stars on a summer league Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) travel team -- has high hopes of joining the Elyria varsity basketball team, alongside his brother.

Dr. Mesko looks forward to his annual examinations of Myles, in which he monitors his ability to raise his surgically-repaired arm over his head, reach around to access his back pocket, and make other movements. Slightly crooked, the right arm is nearly the same length as his left arm and is continuing to grow as it should.

Myles continues making positive progress and looks forward to playing basketball for his high school and recreational teams. (Courtesy: Cleveland Clinic)

For facing his diagnosis and treatment with remarkable strength and bravery, and for pursuing the sport he loves, Myles received the 2025 Jim Donovan Courage Award presented by Cleveland Clinic Sports Medicine during the 26th Greater Cleveland Sports Awards ceremony, held at Rocket Arena in Cleveland, Ohio.

Dr. Mesko gets a daily reminder of his patient from a drawing he keeps on his office wall, which Myles sketched soon after his diagnosis. It shows a smiling Myles, eyes gazing at his problematic shoulder, with an arrow showing the journey his fibula made to repair it.

“Kids are incredibly resilient,” Dr. Mesko says. “And one of the most fun parts about being an orthopaedic oncologist is finding creative ways to help them and give them the best quality of life possible.”

Related Institutes: Cleveland Clinic Cancer Center, Cleveland Clinic Children's , Orthopaedic & Rheumatologic Institute