With hyperacusis, everyday sounds may seem unbearably loud, painful and even frightening. It often accompanies tinnitus, a condition that involves hearing ringing in your ears. Therapies can help treat symptoms.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/Images/org/health/articles/hyperacusis)

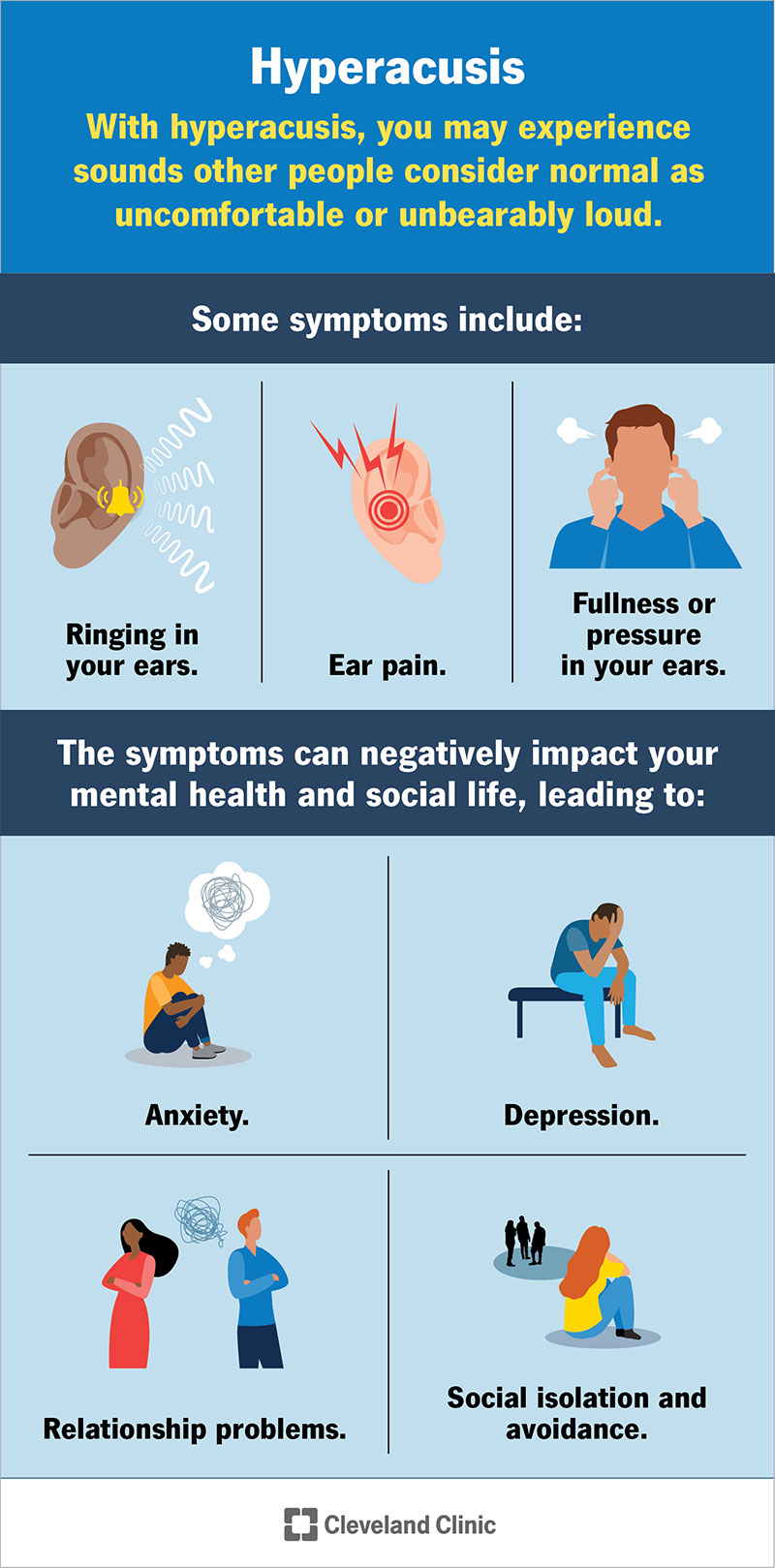

Hyperacusis is a rare hearing disorder where sounds others perceive as normal seem uncomfortably — and often unbearably — loud. It’s also described as decreased sound tolerance, or DST. People with normal hearing experience a range of sounds with varying degrees of loudness. In contrast, people with hyperacusis experience sound in general with the volume turned too high.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Some examples of common sounds in everyday life that may feel intolerable to someone with hyperacusis include:

The experience can take a toll on your mental health, causing you to feel irritable and anxious. Hyperacusis can impact your social life, too. Some people with hyperacusis avoid social situations to reduce the risk of experiencing intense loudness.

Hyperacusis often accompanies tinnitus, a condition often associated with hearing loss that involves ringing, whistling, clicking or roaring sounds in your ears. Still, not all cases of hyperacusis involve tinnitus or hearing loss.

There’s still a lot that doctors don’t know about hyperacusis, including how common it is. Researchers estimate that 3.2% to 17.1% of children and adolescents have hyperacusis, while the range for adults is from 8% to 15.2%.

It’s hard to know for sure how common it is, though. People with hyperacusis describe their symptoms differently based on their unique experiences. Also, there isn’t a single, widely accepted way to screen for or measure hyperacusis. Researchers are still learning about hyperacusis, including how many people have it.

Advertisement

With hyperacusis, you may experience sounds other people consider normal as uncomfortable, unbearably loud, painful or even frightening. The loudness may be mildly annoying or so intense that it causes you to struggle with your balance or experience seizures.

Other symptoms may include:

These symptoms can negatively impact your mental health and social life. The constant experience of feeling overwhelmed with intense, unpleasant sounds can lead to:

Symptoms may intensify if you feel stressed or tired or if you anticipate having to interact in spaces that you fear will be unpleasantly loud.

Researchers are still trying to understand what causes hyperacusis. It’s likely that the structures in your brain that control how you perceive stimulation make sounds seem louder. With hyperacusis, your brain perceives sounds as loud regardless of their frequency — or whether the sound falls in the low range (like thunder rumbling), medium range (like human speech) or high range (like a siren or whistle).

Various theories exist. It’s possible that damage to parts of your auditory nerve causes hyperacusis. Your auditory nerve carries sound signals from your inner ear to your brain so you can hear. Another theory is that damage to the facial nerve causes hyperacusis. The facial nerve controls the stapedius muscle, which regulates sound intensity in your ear. Many conditions associated with hyperacusis (Bell’s palsy, Ramsay Hunt syndrome and Lyme disease) involve facial nerve damage.

Still, there isn’t a single cause that explains all cases of hyperacusis. Instead, it’s associated with multiple possible contributing factors and conditions.

Contributing factors include:

Hyperacusis often accompanies conditions like tinnitus (up to 86% of people) and Williams syndrome (as many as 90% of people). Nearly half of the people diagnosed with hyperacusis also have a behavioral health condition, like anxiety.

Advertisement

Conditions associated with hyperacusis include:

Some people develop hyperacusis symptoms following surgery or as a reaction to a medication.

Getting diagnosed can be difficult because not all healthcare providers are familiar with hyperacusis. You may need to see an ear, nose and throat specialist and/or an audiologist to help identify the problem.

Diagnosis may include:

Advertisement

Your healthcare provider may order imaging procedures if they suspect your hyperacusis results from a structural issue like facial nerve paralysis. They may also order lab work if they suspect that your hyperacusis relates to a condition like Lyme disease.

There isn’t a standard treatment for hyperacusis. Instead, treatments usually involve reducing physical symptoms and teaching coping strategies to handle the mental stress of hyperacusis. Treatments include:

Advertisement

There isn’t a cure for hyperacusis, but depending on what’s causing it, your symptoms may improve in time. For example, hyperacusis following surgery may go away once you heal from the procedure. People with Ménière’s disease may notice an improvement if the disease goes into remission.

Healthcare providers and medical researchers are still studying the long-term effects of hyperacusis. For many people, hyperacusis is a long-term condition they learn to manage with treatment. Others experience symptom relief following surgery or once the underlying condition resolves.

Many people with hyperacusis symptoms start by trying to drown out the sounds around them with earplugs or headphones. They may avoid social settings. But these options can make things worse. People who wear headphones or earplugs may experience sound even more intensely once they remove them, and social isolation can lead to (or worsen) behavioral health issues.

Don’t try to manage symptoms on your own. Instead, see a healthcare provider if you’re experiencing hyperacusis symptoms. It may take a while to identify what’s likely causing the issue, but there are therapies that can help.

No, hyperacusis isn’t a mental illness. Hyperacusis is a hearing disorder commonly associated with mental health conditions, including anxiety and depression. Living with the excessive loudness characteristic of hyperacusis can affect your mental health. Anxiety about encountering sound and isolating yourself to spare your hearing can worsen hyperacusis symptoms.

See a healthcare provider if you’re experiencing uncomfortably loud sounds. Trying to drown out the sound with noise-canceling headphones or earplugs may only worsen your symptoms in the long run. It may take some time to discover what’s likely causing your condition, but there are therapies that can help. Sound therapy and CBT have helped people with hyperacusis cope with their symptoms. If an underlying condition causes hyperacusis, seeking treatment can help.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

If you have conditions affecting your ears, nose and throat, you want experts you can trust. Cleveland Clinic’s otolaryngology specialists can help.