Alport syndrome is when variations in your collagen genes affect how well your kidneys work. Symptoms include blood and protein in your pee. It may also affect your vision and hearing. It can eventually cause kidney failure. Treatment includes ACE inhibitors and ARBs.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/alport-syndrome)

Alport syndrome is a genetic disorder that affects how well your kidneys work. Your kidneys remove waste products and extra fluids from your blood. They leave your body as pee. In most cases, one or both of your biological parents must have Alport syndrome to pass it down to you.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

If you have Alport syndrome, your kidneys don’t make normal type IV collagen chains. Type IV collagen chains consist of three individual collagen chains — alpha 3, alpha 4 and alpha 5. In most people, they twist together like rope. But sometimes, your body doesn’t make one of the chains. Or your body makes the chains, but there’s something wrong with them.

When these chains don’t work the way they should, they affect the filters in your kidneys. These filters keep blood cells and protein in your blood instead of your pee. Over time, your kidneys have a harder time filtering your pee. This increases your risk of kidney failure.

Your eyes and ears also have type IV collagen. If you have Alport syndrome, it can also affect your vision and hearing. Healthcare providers sometimes call kidney problems, loss of hearing and vision problems the clinical triad of Alport syndrome. But you don’t need to have all three to have Alport syndrome.

Experts believe Alport syndrome is rare. Previously, they believed it affected fewer than 1 in 2,000 people. There are fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S. who have Alport syndrome. But genetic testing is becoming more accessible, and experts are finding more people with milder forms of Alport syndrome. They may also have focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS). FSGS is due to Alport syndrome. As a result, Alport syndrome is likely more common than the current data suggests. Studies in Europe suggest that as many as 1 in 100 people may have some genetic variation in the type IV collagen genes.

Advertisement

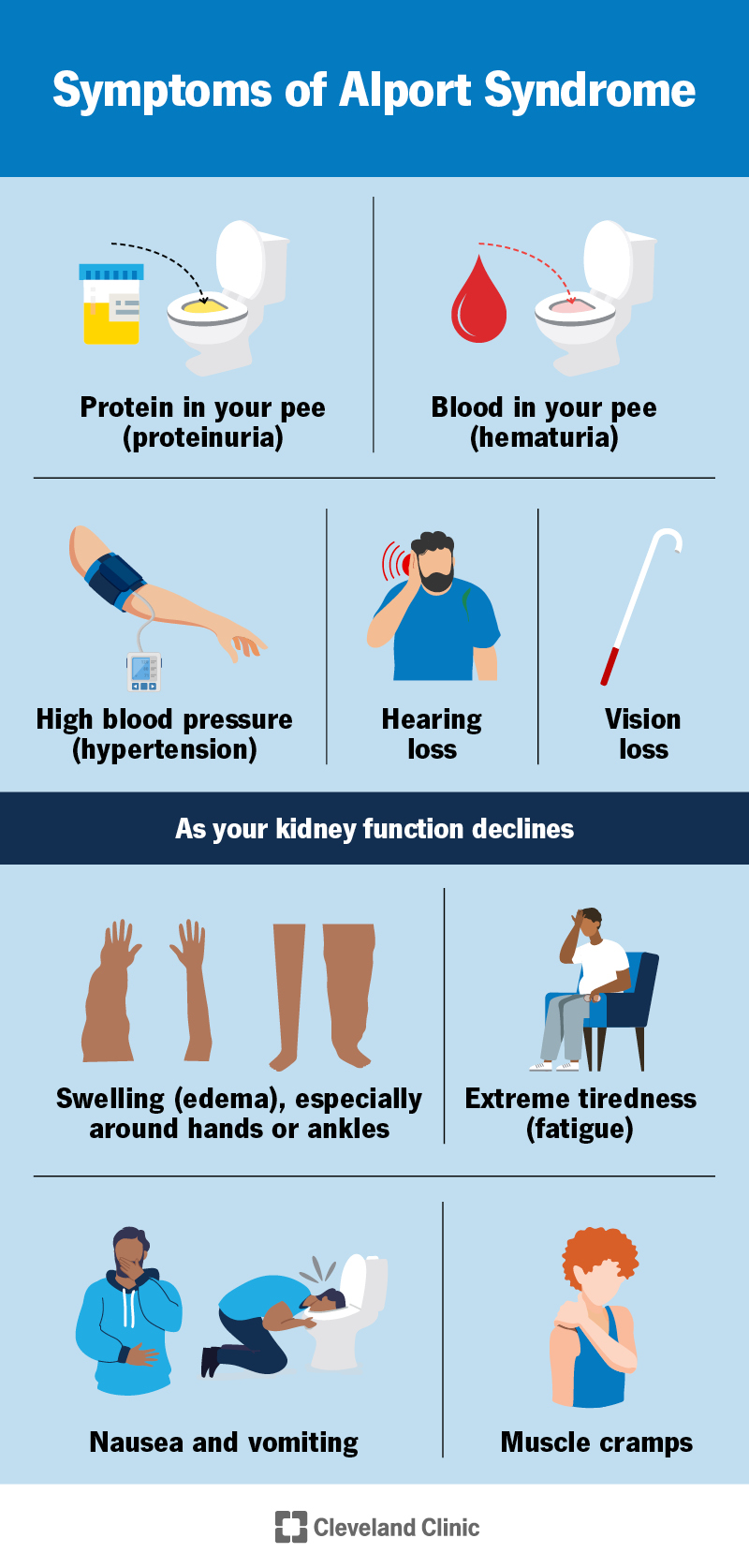

Alport syndrome signs or symptoms can vary according to which type you have. But the main signs include:

As your kidney function gets worse, CKD develops. Most people don’t have symptoms from CKD until they reach kidney failure. Kidney failure symptoms include:

Variations in your type IV collagen genes cause Alport syndrome. Type IV collagen is an important protein in your kidneys’ filtration membranes (glomerular basement membranes, or GBM).

The GBM has three layers that remove toxins, excess fluids and other wastes from your blood. It also keeps blood cells and proteins in your blood instead of letting them enter your pee. When the GBM doesn’t work as it should, blood and proteins can leak into your pee.

Alport syndrome is an inherited condition. That means one or both of your biological parents pass it down to you. But in about 15% of cases, it can develop even if neither parent has the variant gene.

You can’t prevent Alport syndrome. But being aware of your biological family history can help you detect it early. It can also help prevent you from passing it on to your biological child.

If a provider finds blood in your pee, it’s a good idea to get additional testing. This applies particularly if you’re young or providers find blood over several tests.

Your healthcare provider will:

Advertisement

They may recommend tests to help make an official diagnosis. These include:

Genetic testing can also help determine the type of Alport syndrome you have.

There are three genetic types of Alport syndrome:

X-linked Alport syndrome (XLAS) is the most common type of Alport syndrome. Experts used to think that about 60% to 80% of all cases of Alport syndrome were XLAS. But as they diagnose more mild cases, they think it makes up about 40-50% of cases. It relates to your X chromosome. It’s where the gene that makes your alpha 5 chain (COL4A5) is.

Males have one X chromosome and one Y chromosome. Females have two X chromosomes. Males only have the abnormal X chromosome. They’re more likely to have severe symptoms. Females have one abnormal X chromosome and one normal X chromosome. They’re more likely to have milder symptoms. All males with XLAS will have symptoms. Most will develop kidney failure. Most females will have blood in their pee. But fewer will have problems with kidney function. About 30% will develop kidney failure in their lifetimes.

Advertisement

Males pass their Y chromosome to their male children. They can’t pass XLAS to them. But males pass their X chromosome to their female children. Therefore, any female children they have will have Alport syndrome.

Females pass one of their X chromosomes on to their child of either sex. They have a 50% chance of passing XLAS to any of their children.

Autosomal recessive Alport syndrome (ARAS) is when both biological parents have the altered gene. Both parents must pass the altered gene on to their child. But parents with an autosomal recessive trait don’t have any symptoms. Or they may have mild symptoms, like blood in their pee. They usually don’t know they have it. About 1 in 4 children will get an autosomal recessive trait if both parents have it. ADAS doesn’t depend on sex. The inheritance and severity are the same in everyone.

In Alport syndrome, the genes that encode the alpha 3 (COL4A3) and alpha 4 (COL4A4) proteins are on chromosome 2. In ARAS, the variations (mutations) must occur on the same chromosome on both genes on chromosome 2. For example, both copies of COL4A4. Chromosome 2 encodes the alpha 3 and alpha 4 proteins.

If you have ARAS, there’s a 50% chance of passing one of the abnormal genes to any of your biological children. This usually doesn’t result in Alport syndrome. But there’s a 25% chance of passing both abnormal genes. If this happens, your child will have ARAS.

Advertisement

About 15% of all cases of Alport syndrome are ARAS.

Digenic Alport syndrome is a different form of Alport syndrome. Like ARAS, two gene variants must be present. But unlike ARAS, the variants are on different genes.

Autosomal dominant Alport syndrome (ADAS) is when a variation on only one of the genes in a pair causes Alport syndrome. The variation is on one of the genes in chromosome 2. ADAS doesn’t depend on sex. The inheritance and severity are the same in everyone.

If you have ADAS, there’s a 50% chance of passing the abnormal gene on to your biological children. If this happens, ADAS will develop.

About 40-50% of all cases of Alport syndrome are ADAS.

ADAS’s path may vary, even within the same biological family. Some people don’t have blood in their pee. Kidney failure from ADAS is less common than XLAS or ARAS.

Your healthcare provider may prescribe treatments to help slow down kidney decline and delay failure. These may include:

Your provider may also recommend cutting back on the amount of sodium (salt) that you eat. This helps lower your blood pressure and keep your kidneys and heart healthy.

There isn’t a cure for Alport syndrome. Experts are working on gene therapies that fix the abnormal genes. But they’re not successful yet. And if they can develop a successful gene therapy, it can take years for approval. Talk to your provider if you have Alport syndrome and are interested in participating in a research trial.

Yes and no. A kidney transplant will give you a kidney with normal type IV collagen and GBMs. Alport syndrome won’t come back in a new kidney. But kidney transplants can’t help with hearing loss or problems with your eyes.

Contact a healthcare provider if you have blood in your pee or notice hearing or vision changes. These may be signs of Alport syndrome.

You should also schedule an appointment with a healthcare provider if any of your biological family members have Alport syndrome. Your provider may recommend blood and pee tests.

If a provider diagnoses you with Alport syndrome, you may wish to ask:

It depends on what type of Alport syndrome you have.

Males who have XLAS and anyone with ARAS often develop kidney failure and hearing loss before 30.

Females who have XLAS usually have an average lifespan. You may only have some symptoms, like hematuria or proteinuria. Or you may have CKD or kidney failure and hearing loss. Each person has a different response. But 20% of females will develop kidney failure by 60. About 30% will develop it in their lifetimes.

People with ADAS usually have an average lifespan. Hearing loss and kidney failure are less common if you have ADAS. There isn’t enough ADAS research to know for sure who will develop kidney failure and who won’t.

CKD and kidney failure usually shorten the lifespan of people who have Alport syndrome. Without dialysis or a kidney transplant, kidney failure is fatal. Even with treatment, kidney failure and CKD increase your risk of dying from heart disease, stroke and infections. A kidney transplant may help bring your life expectancy closer to average.

Your healthcare provider will give you a better idea of what to expect according to your situation.

You may feel a wide range of emotions upon receiving an Alport syndrome diagnosis. How will this affect my life? Does anyone else in my family have it? Will I pass it on to my children?

It’s important to give yourself time and space to understand it and learn about your treatment options. Knowing your choices and what to expect can help you process your emotions. You make the ultimate decisions about your health. Your provider is here for you and can give you information and guidance. Talk to them if you have any questions or need support or advice.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

If you have a condition that’s affecting your kidneys, you want experts by your side. At Cleveland Clinic, we’ll work with you to craft a personalized treatment plan.