Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is a condition where weak muscles in your pelvis cause one or more organs (vagina, uterus, bladder and rectum) to sag. In more severe cases, an organ bulges onto another organ or outside your body. Your healthcare provider can recommend treatments to repair the prolapse and relieve your symptoms.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/24046-pelvic-organ-prolapse)

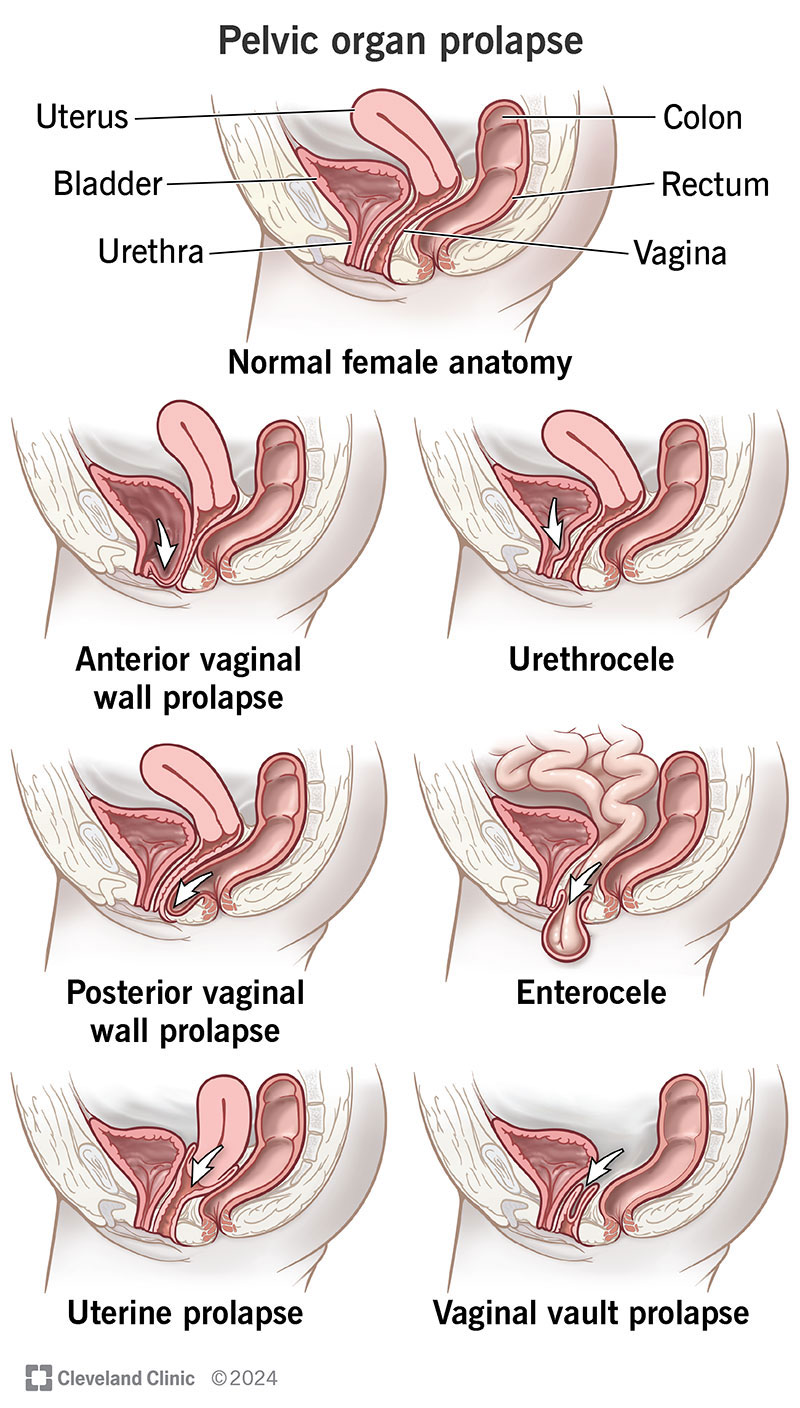

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is when your pelvic organs (vagina, uterus, bladder, rectum) drop from their typical positions. It happens when your pelvic floor (the muscles, ligaments and tissues that support your pelvic organs) become too weak to hold your organs in place. Your pelvic floor supports the organs in your pelvis from underneath — almost like a hammock. If these supports become too loose, the organs they support shift out of place or sag into the vagina. Your pelvic floor can weaken due to things like childbirth or aging.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

With mild cases of POP, your organs may drop slightly. In severe cases, they may extend outside your vagina and cause a bulge. People with a prolapse typically describe it as fullness or pressure in their vagina, as if something were falling out. Your exact symptoms will depend on what type of prolapse you have and how severe it is.

There are nonsurgical and surgical options to treat pelvic organ prolapse. Your healthcare provider can discuss what your options are based on your situation.

The type of prolapse you have depends on where the weaknesses are in your pelvic floor and what organs the weakness affects.

Advertisement

Around 3% to 11% of women experience POP. About 37% of women with pelvic floor disorders, including POP, are between ages 60 and 79. Over half are 80 or older.

These figures may not be exact because many don’t seek treatment. Often, conditions that affect the genitals go untreated because you may feel embarrassed about your symptoms. It’s important to know that you’re not alone and many people have a form of pelvic organ prolapse.

The most common symptom is feeling a bulge in your vagina, as if something were falling out of it. Other symptoms include:

Your symptoms depend on where the prolapse is. Telling your healthcare provider about your symptoms helps them locate the spots where your pelvic floor is weakest.

Many people don’t tell their provider about their symptoms until they experience trouble peeing and pooping, or until sex becomes painful. These side effects often occur with POP. Symptoms include:

Your pelvic floor can weaken for many reasons. It happens most often when your pelvic floor muscles, ligaments and tissues overstretch. It can also happen due to underuse when the muscles don’t work enough.

Any of the following factors make you more at risk for pelvic organ prolapse:

Advertisement

Pelvic organ prolapse can be uncomfortable and affect your quality of life. Other than urinary and fecal incontinence, some of the other possible complications of a prolapse are:

During your appointment, your healthcare provider will review your symptoms and perform a pelvic exam. During the exam, your provider may ask you to cough so that they can see the full extent of your prolapse when you’re straining and when you’re relaxed. They may examine you while you’re lying down and while you’re standing. Often, a pelvic exam is all it takes to diagnose a prolapse.

Additional tests may include:

Advertisement

The Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) system classifies POP based on how far your pelvic organs drop relative to your hymen. Your hymen is a piece of tissue at the exit of your vagina.

The scale ranges from zero to four:

Pelvic organ prolapse may affect different organs in different ways. For example, you could have a stage three bladder prolapse and a stage one uterine prolapse.

Your treatment plan will depend on how severe the prolapse is, where it is and how much your symptoms affect you. There are surgical and nonsurgical treatment options. For example, you may not need treatment if the prolapse is mild and not bothering you. Your provider can discuss all possible treatment methods with you and help you decide what may work best for your situation.

Advertisement

Nonsurgical treatment focuses on managing your symptoms and improving your quality of life. Your results may not be permanent depending on how severe the prolapse is. But many people prefer nonsurgical options or determine that this method is best for them.

Treatments for pelvic organ prolapse that don’t involve surgery include:

Surgery may be an option if your symptoms don’t improve with conservative treatments or if your provider believes surgery gives you the best quality of life moving forward. Be sure to discuss the risks and benefits of surgery with your provider.

There are several different methods your surgeon may choose to fix pelvic organ prolapse. Two main types of surgeries are available: obliterative surgery and reconstructive surgery.

Obliterative surgery narrows the opening of your vagina, preventing the organs from slipping out. This may eliminate your ability to have penetrative sex.

Reconstructive surgery repairs the weak parts of your pelvic floor and moves the organs back to their typical position.

There isn’t one specific stage that requires surgery to treat a pelvic organ prolapse. It depends on factors like how your symptoms impact your life and if you plan on having children. It’s typically more common to need surgery if you have a third or fourth stage prolapse.

It’s important to discuss all treatment options with your healthcare provider, including whether they recommend surgery or prefer nonsurgical options first.

Yes, with treatment, it can go away. With mild POP, you can strengthen your muscles so that they hold the organs in their correct locations. Reconstructive surgeries strengthen the weaknesses in your pelvic walls so that your organs return to their original locations.

Yes. With more severe prolapse, you may have to push the bulging organ back into place, especially when pooping or peeing. But, this fix is temporary. See your healthcare provider for treatment if a pelvic organ prolapse is this severe.

Your outlook depends on several things like where the prolapse is, how severe it is, your symptoms and the treatment options you pursue. Be sure to think carefully about what you hope to accomplish with treatment. Weigh the pros and cons of each treatment option with your healthcare provider. Discuss how treatment will help you live a more comfortable life.

The one thing to remember is that pelvic organ prolapse is treatable and you don’t have to live with the discomfort. Seek help from a healthcare provider and let them tell you your options. Most people who have pelvic organ prolapse find relief from their symptoms with treatment.

Many causes of POP are out of your control. But you can put healthy habits into place to reduce your risk.

Contact a healthcare provider if you have signs of pelvic floor prolapse. Possible symptoms include:

Just because pelvic organ prolapse isn’t life-threatening doesn’t mean you have to accept it as part of life. It can cause symptoms that prevent you from living your life to the fullest and doing things you enjoy. Know that you aren’t alone and pelvic floor dysfunction is very common in women. Don’t be embarrassed to talk to your healthcare provider if you suspect you have a weak pelvic floor. They can suggest procedures, medical devices and even lifestyle modifications that can repair the prolapse and improve your quality of life.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

From routine pelvic exams to high-risk pregnancies, Cleveland Clinic’s Ob/Gyns are here for you at any point in life.