A stomach ulcer occurs when stomach acid eats through your protective stomach lining, producing an open sore. Typical signs and symptoms include burning stomach pain and indigestion. Ulcers heal when the conditions causing them go away. A healthcare provider must identify the cause of your ulcer to recommend the right treatment.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/Images/org/health/articles/22314-stomach-ulcer.jpg)

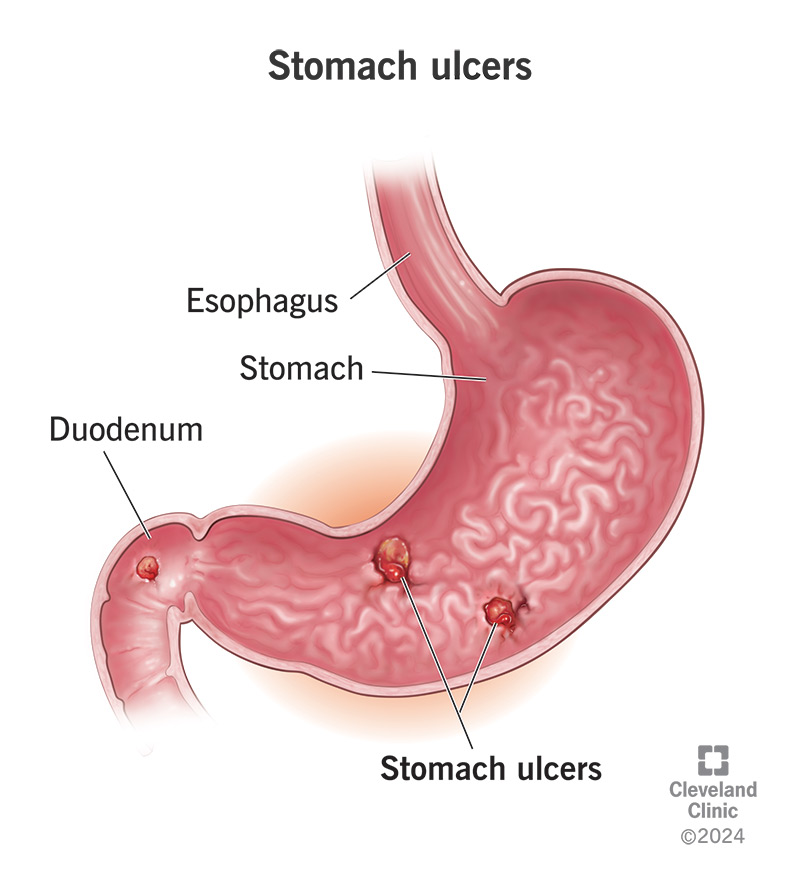

A stomach ulcer (or gastric ulcer) is an open sore in your stomach lining. It’s a common cause of focal stomach pain — pain that you can feel coming from a particular spot — often with a burning or gnawing quality. But not all stomach ulcers cause noticeable symptoms.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Stomach ulcers are common and treatable, but they can become serious if they go too long without treatment. Some ulcers bleed continuously, which can lead to significant blood loss over time. Some can continue to erode through your stomach wall until there’s a hole.

Sometimes, a stomach ulcer is called a peptic ulcer. Stomach ulcers are one type of peptic ulcer disease.

In the U.S., healthcare providers treat about 4 million stomach ulcers every year. Ulcers are common in our society because their main causes are also common. These include use of over-the-counter (OTC) pain medications and a widespread bacterial infection called H. pylori.

A stomach ulcer feels like a sore spot in your stomach, which is located in your upper abdomen, between your breastbone and your belly button, a little to the left.

Typical ulcer pain feels like an acid burn in your stomach, or like something is eating it. This feeling isn’t an illusion. Stomach acids, enzymes and other chemicals are eating away at the wound.

Many people experience indigestion with stomach ulcers, which means burning stomach pain together with a feeling of fullness. You might feel full shortly after you’ve started eating and/or long after you ate.

Advertisement

People also report:

These symptoms are related to the conditions that caused your stomach ulcer.

Some people don’t feel their stomach ulcers at all. These are called silent ulcers. You might not experience any symptoms until you develop complications, like bleeding or a perforation (hole).

These symptoms might include:

If you develop any of these symptoms, see a healthcare provider right away.

Bleeding ulcers: Active bleeding from a stomach ulcer can be mild to severe and can affect you a little or a lot. Moderate blood loss can lead to anemia, while severe blood loss can lead to shock.

Perforated ulcers: An ulcer that erodes all the way through your stomach wall is rare, but it’s an emergency. Stomach acids and bacteria that leak from the hole into your abdominal cavity can cause an infection. Infection in your abdominal cavity can easily spread to your bloodstream and lead to sepsis.

The two most common causes of stomach ulcers are the H. pylori bacterial infection and overuse of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). These two causes together account for about 99% of the stomach ulcers U.S. healthcare providers treat.

H. pylori is a very common bacterial infection that affects up to half of people worldwide. It primarily lives in your stomach. In many people, it doesn’t seem to cause any problems. But sometimes, it overgrows and takes over. As the bacteria continue to multiply, they eat into your stomach lining, causing chronic inflammation that leads to gastric ulcers.

NSAIDs (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) are common over-the-counter pain relievers, like ibuprofen, naproxen and aspirin. These medications irritate your stomach lining on contact, and they also inhibit some of the chemicals that defend and repair it.

Your stomach lining is designed to recover from these minor insults. But if you take too many NSAIDs too often, eventually it won’t be able to keep up with repairs. The more the protective lining wears away, the fewer resources it has to recover.

Less common causes of stomach ulcers include:

Advertisement

Normal lifestyle factors, like your day-to-day stress levels and what you eat and drink, don’t cause stomach ulcers. But they can make your symptoms worse if you have one. Anything that makes your stomach more acidic can irritate the wound, including:

Your healthcare provider will begin by asking you about your symptoms and medical history. They’ll want to know if you frequently use NSAIDs or have a history of H. pylori infection. If signs point to an ulcer, they’ll take a look inside your stomach to find it.

Your healthcare provider will want to check for H. pylori infection, then look for the ulcer itself inside your stomach. They can do these things in a few different ways. One common method is an upper endoscopy exam, which can accomplish both at once.

An upper endoscopy (EGD test) goes inside your stomach with a tiny camera on a long, thin tube (endoscope). The tube goes down your throat while you’re under sedation. Through the tube, a healthcare provider can pass long, narrow tools.

Your provider can use these tools to take a tissue sample (biopsy) and test it for H. pylori. They can also use tools to treat a stomach ulcer on sight. This is especially helpful if your provider suspects complications like bleeding.

Advertisement

Although endoscopy is the best method, sometimes an imaging test like an upper GI X-ray series can identify a stomach ulcer without going inside your stomach. Specific tests for H. pylori infection include a breath test, blood test or stool test.

Video content: This video is available to watch online.

View video online (https://cdnapisec.kaltura.com/p/2207941/sp/220794100/playManifest/entryId/1_6v09sd17/flavorId/1_5f3sgelj/format/url/protocol/https/a.mp4)

What’s the difference between GERD and stomach ulcers?

If it turns out you don’t have a gastric ulcer, you might have:

Your stomach lining will begin to heal when the cause of the ulcer goes away. If you can make it go away without treatment — for example, if your ulcer is due to NSAID use and you stop taking NSAIDs — this might be enough for the ulcer to heal by itself.

On the other hand, if you have an H. pylori infection, you’ll probably need antibiotics to make it go away. Your provider can also prescribe other medications to help reduce the acid in your stomach and protect your stomach lining to promote faster healing.

Advertisement

Healthcare providers treat most ulcers with a combination of medications to reduce stomach acid, coat and protect the ulcer during healing, and kill any infection involved. Occasionally, you might need a procedure to stop bleeding or repair a hole.

Medications to treat stomach ulcers include:

Antibiotics. If you have an H. pylori or other bacterial infection, your healthcare provider will prescribe some combination of antibiotics to kill the bacteria.

Common antibiotics for H. pylori infection include:

Cytoprotective agents. These medicines help to coat and protect your stomach lining. Healthcare providers often prescribe them to treat and prevent stomach ulcers related to NSAID use. They include:

Histamine receptor blockers (H2 blockers). These drugs reduce stomach acid by blocking the chemical that tells your body to produce it. They include:

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). These drugs help reduce stomach acid and also coat and protect your stomach lining to promote healing. PPIs include:

If you have a complicated ulcer, your provider may need to treat it directly. They can usually do this during your endoscopy exam. Providers treat bleeding by cauterizing or injecting medication into the wound. If you have a hole, a colorectal surgeon may need to stitch it.

Rarely, some people have persistent stomach ulcers that don’t respond to treatment or that keep coming back. This can cause chronic pain and scarring in your stomach. Scar tissue may even obstruct the outlet at the bottom of your stomach. This might require surgery to:

If you’re taking your medications as prescribed and avoiding things that might aggravate the ulcer, it should heal within a few weeks. Your healthcare provider may conduct follow-up tests to make sure the ulcer has healed, and any infection has cleared.

Most people will only need short-term treatment, but some people have chronic conditions that can cause chronic ulcers. For example, Zollinger-Ellison syndrome causes your stomach to produce too much acid. Chronic conditions might need long-term medication.

To prevent a stomach ulcer, take steps to:

Always seek medical care for a stomach ulcer. While you may be able to manage your symptoms temporarily with over-the-counter medications, like antacids and bismuth subsalicylate, these won’t heal the ulcer. You need to address the underlying cause.

An untreated ulcer can lead to serious complications, even if you don’t have severe symptoms. The major cause of stomach ulcers, H. pylori infection, can also lead to other complications. For example, it’s a risk factor for developing stomach cancer.

Seek emergency care if you have:

Stomach ulcers are common and treatable, but they can also be serious. Even when they don’t cause symptoms, they still need treatment. While lifestyle changes can help you feel better, it’s important to identify and treat the underlying cause.

A stomach ulcer means that your natural stomach acid is overwhelming your protective stomach lining. That’s a situation that can only get worse if it isn’t managed. Your healthcare provider can help prescribe the right treatment for your condition.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

When you have a stomach ulcer, it can feel like your body is attacking itself. Cleveland Clinic’s digestive experts can help with a custom treatment plan.