Barrett’s esophagus is a change in the cellular structure of your esophagus lining. It’s a risk factor for cancer, but the risk is low. It usually occurs in people with chronic, untreated acid reflux (GERD). Treating the underlying condition can help prevent Barrett’s esophagus from progressing to cancer.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Barrett’s esophagus is a change in the cellular structure of your esophagus lining. Your esophagus is the swallowing tube that carries food from your mouth to your stomach. Like all of your gastrointestinal (GI) tract, your esophagus has a protective mucous lining on the inside. But if something irritates this lining for a long time, it can damage the tissues. Sometimes, this damage actually reprograms the cells.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

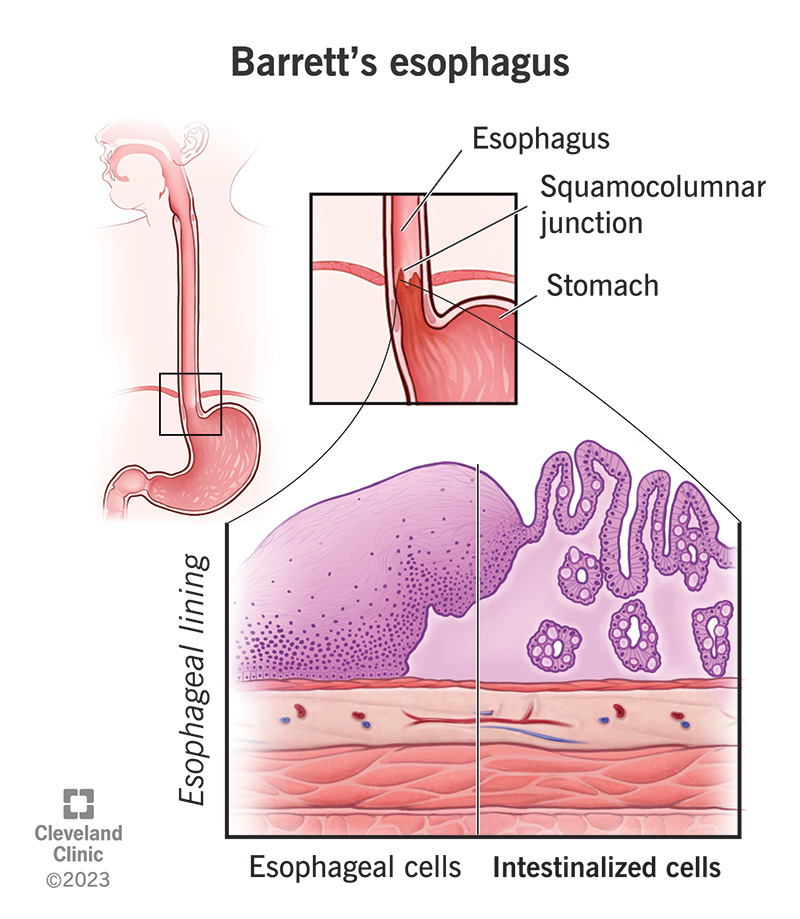

These changes affect the structure and appearance of your esophagus lining. To scientists, it now looks more like the lining of your intestines. They call this intestinal metaplasia. Metaplasia is when tissues in your body replace themselves with a different type of tissue that isn’t normally found there. This is a risk factor for cancer. Although the risk is small, metaplasia makes cancerous changes more likely.

Because of the small chance it might progress to esophageal cancer, healthcare providers like to keep an eye on Barrett’s esophagus. But the risk is only about half a percent per year. Cellular changes happen slowly, and metaplasia passes through another precancerous stage (dysplasia) before progressing to cancer. If your provider notices any dysplasia, they’ll remove it to stop it from progressing further.

On its own, Barrett’s esophagus doesn’t produce any symptoms. But if something is irritating your esophagus lining for a long time, you’re likely to have symptoms from that. Chronic esophagitis — inflammation in your esophagus — may feel like heartburn or chest pain on the lower end, or like a sore throat if it’s higher. It may make your esophagus feel swollen or cause difficulties swallowing.

Advertisement

It takes years of chronic esophagitis to damage your esophagus tissues enough to trigger metaplasia. If you have any chronic symptoms, even if they’re mild or they come and go, check in with a healthcare provider. Chronic acid reflux is the most common cause of esophagitis leading to Barrett’s esophagus. If you ever feel or taste stomach juices backwashing into your esophagus after you eat, take notice.

Scientists don’t completely understand why Barrett’s esophagus occurs, but it seems to relate to chronic irritation or injury inside your esophagus. It may be a result of constant cellular repair. Most people who develop Barrett’s esophagus have had gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) for at least 10 years. But not everyone fits this profile, and other irritants may also lead to Barrett’s esophagus.

The ways that Barrett’s esophagus changes your esophagus lining suggest that it’s trying to protect itself. Your esophagus lining normally has some protection from acids and other irritants, but not as much as your intestinal lining. Since acids and digestive enzymes do most of their work inside your small intestine, it needs extra protection. Intestinal metaplasia in your esophagus suggests that it does, too.

You may be more likely to develop Barrett’s esophagus if you:

A gastroenterologist, a specialist in gastrointestinal diseases, usually diagnoses Barrett’s esophagus. They’ll look inside your esophagus for evidence of the tissue changes and take small tissue samples to confirm them (biopsies). They’ll do this in a procedure called an endoscopy. This means putting a tiny camera on a long tube down your throat to examine your esophagus, while you’re under sedation.

In general, normal esophageal lining is pale pink and smooth, while intestinal metaplasia is salmon-colored and coarse. But inflammation in your esophagus could obscure these features. Your provider might need to take multiple biopsy samples from different places to study under a microscope. This is how they’ll confirm the structural changes in the cells of your esophagus lining (epithelium).

Normal esophageal epithelium consists of stratified squamous cells. These are flat, square cells arranged in layers (“squamous” means flat, and “stratified” means in layers). The lower part of your GI tract (your intestine) is lined with columnar epithelium. Columnar cells are rectangular and lay side-by-side in a single layer. If these appear in your esophagus, your provider will diagnose Barrett’s esophagus.

Advertisement

Your provider might describe your condition as:

They might define the stage as:

People with Barrett’s esophagus may also have:

Treatment for Barrett’s esophagus includes:

Chronic acid reflux, the most common condition leading to Barrett’s esophagus, is treatable. Healthcare providers usually recommend a combination of diet and lifestyle changes and acid-blocking medications. Medications called proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are very effective in protecting your esophagus from acid reflux and helping the tissues heal. A minor procedure can also fix the underlying defect that causes it.

Advertisement

Prescription medications to treat acid reflux include:

You’ll need to have periodic endoscopy exams to check on your metaplasia and see if it’s progressing. Your provider will tell you how often you should have them, depending on whether you have any dysplasia yet (precancerous changes). Barrett’s esophagus without dysplasia only needs to be examined every few years. Barrett’s esophagus after dysplasia should be examined yearly.

Dysplasia is the next stage of cellular changes in your tissues between metaplasia and cancer. If a pathologist confirms you have dysplasia, they’ll characterize it as either low-grade or high-grade (mild or severe). Your provider may recommend treatment or more frequent surveillance for low-grade dysplasia. For high-grade dysplasia, they’ll recommend treatment to remove the affected tissue.

Procedures to treat dysplasia include:

Advertisement

Metaplasia won’t go away by itself, though medical procedures can remove the affected tissue. Healthcare providers don’t recommend these procedures unless you have dysplasia. Barrett’s esophagus without dysplasia won’t affect you much. It just means you have to have periodic endoscopy exams. But it’s important to address what’s injuring your esophagus. You can make GERD go away.

If you remove the affected tissue and stop whatever was injuring your esophagus, Barrett’s esophagus may be cured. But it can return. Sometimes, a layer of metaplasia hides underneath a layer of new, normal tissue. Sometimes, the injury continues, and so the process of metaplasia continues. Because of this risk, your healthcare provider will probably recommend continued surveillance, just to be safe.

You can live a normal life with Barrett’s esophagus, as long as it doesn’t continue to progress. Precancerous or cancerous changes will affect your life expectancy. But most people with Barrett’s esophagus will never develop these changes. In general, your prognosis (outlook) is better the sooner you seek treatment. You can prevent and even remove cancerous changes if you catch them early enough.

The known causes of chronic esophagitis leading to Barrett’s esophagus are treatable. Most people have these conditions for a long time before they progress to Barrett’s esophagus. You can help prevent this from happening by paying attention to your symptoms and seeking treatment for these conditions. You can also reduce your risk by avoiding or quitting smoking. A healthcare provider can help you quit.

Barrett’s esophagus by itself won’t harm you. But it’s an important sign of prior injury. It’s also a mild warning of possible future harm. What it means is that you need to address the underlying cause of injury to your esophagus. The common causes of esophagitis are usually treatable, and treating them can greatly improve your quality of life. Consider it a bonus if you can also reduce your risk of cancer.

Barrett’s esophagus is a quiet cancer risk, but you don’t have to handle it alone. Cleveland Clinic is here to help you manage this disease and stay healthy.

Last reviewed on 03/18/2024.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.