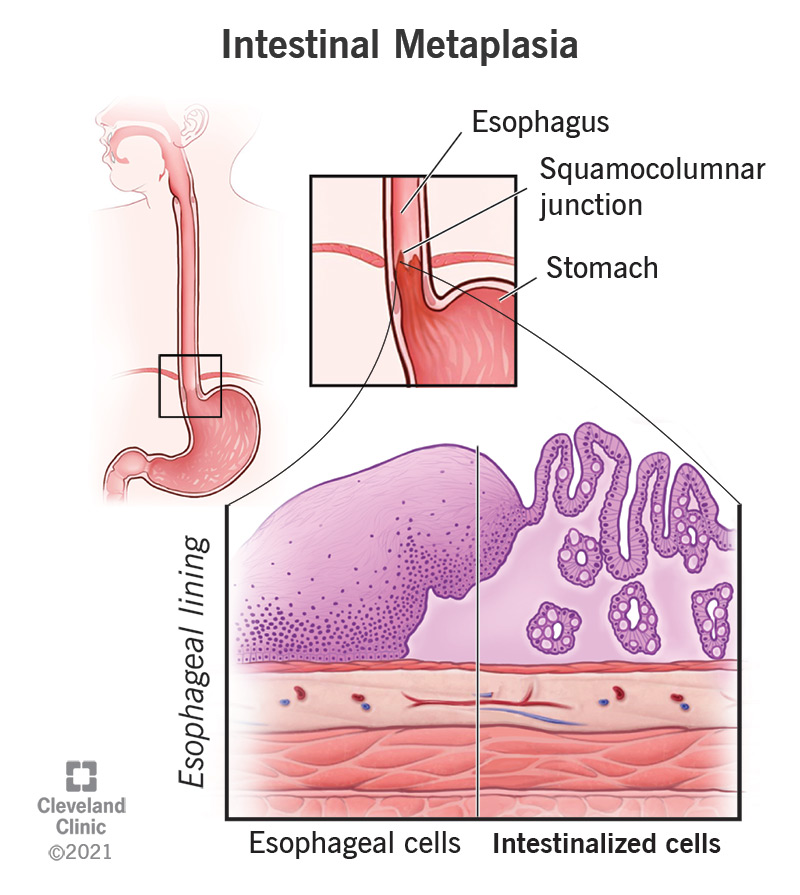

Chronic inflammation of the esophagus (esophagitis) or stomach (gastritis) can lead to intestinal metaplasia, a cellular change in the tissues. The cells in the lining of the stomach or esophagus change to resemble the tissues that line the intestines. This cellular change is a precursor to cancer.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/22215-intestinal-metaplasia)

Intestinal metaplasia is a transformation of the cells in the lining of your upper digestive tract, often the stomach or the esophagus (food pipe). It’s called “intestinal” metaplasia because the cells change to become more like those that line the intestines. When doctors find intestinal metaplasia, it looks like the mucosal lining of your esophagus or stomach has been replaced with intestinal lining. In the esophagus, this condition is also known as Barrett’s esophagus. In the stomach, it may be called gastric intestinal metaplasia.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Scientists believe metaplasia is a response to chronic irritation of cells. This irritation comes from a variety of environmental factors, including smoking and alcohol. Intestinal metaplasia in the esophagus (Barrett’s esophagus) could occur because of chronic acid reflux from your stomach into your esophagus. You may be more likely to have Barrett’s esophagus if you have a history of chronic acid reflux (GERD), smoking and/or drinking.

On the other hand, intestinal metaplasia in the stomach is associated with a widespread bacterial infection known as Helicobacter pylori, which can attack the protective mucous lining of the stomach. Another condition called “autoimmune metaplastic atrophic gastritis” can also lead to intestinal metaplasia of the stomach. In this condition, your own body’s immune system attacks the lining of your stomach. This condition is inherited.

Intestinal metaplasia is usually asymptomatic, which means it doesn’t cause symptoms on its own. You may have symptoms related to the cause of the condition, such as chronic acid reflux or H. pylori infection, which cause you to seek medical care. Intestinal metaplasia is usually found during an examination, such as an upper endoscopy or a biopsy, looking for something else. However, in spite of causing no direct symptoms, it's a significant cellular change in your body and one that your healthcare provider will want to keep an eye on. It has the potential to progress into something more serious.

Advertisement

This condition is considered a risk factor for cancer. It’s not cancer, but it’s a step toward it. Cells that have transformed once are more likely to transform again. If they go through another stage of transformation, known as dysplasia, they will become precancerous cells. The next stage after that will be cancer. Intestinal metaplasia may advance to stomach cancer or esophageal cancer over time in a small percentage of people. It’s still not very likely, but your healthcare provider will want to screen you regularly and take steps to prevent metaplasia from progressing if possible.

Your healthcare provider may categorize gastric intestinal metaplasia (IM) based on the extent it's in your stomach:

Your healthcare provider may also categorize gastric intestinal metaplasia based on the degree of cellular transformation:

In low-grade dysplasia, some cells are displaying the beginnings of architectural changes. These are considered precancerous cells, but they don’t appear to be changing aggressively. Your healthcare provider may recommend treating low-grade dysplasia before it progresses.

In high-grade dysplasia, the cells show more complex architectural changes, including branching and budding, but they don’t yet appear to be invasive. This is a step closer to cancer. Your healthcare provider may recommend treating high-grade dysplasia before it progresses.

Since intestinal metaplasia causes no direct symptoms and can only be diagnosed through testing, it’s impossible to know how common it is in the general population. Estimates range between 3% and 20% among all Americans. Gastric IM is more common among those of Hispanic and East Asian descent. Barrett’s esophagus is more common in white men.

Intestinal metaplasia seems to be caused by a reaction to prolonged irritation of the tissues lining the stomach or esophagus. Scientists don’t know exactly why it occurs in some people and not others, but it seems to involve a combination of factors, including:

Advertisement

The primary culprits include:

You may be more at risk of developing IM if you have a history of:

These additional risk factors increase your likelihood of developing intestinal metaplasia:

IM doesn’t cause symptoms on its own. But if you have IM, it means your stomach or esophagus has been exposed to chronic inflammation for a long time. You’re likely to have noticed those symptoms at times.

Advertisement

IM is often discovered by accident while screening for other conditions, usually during an upper endoscopy exam. During the exam, the endoscopist will see tongues of salmon-colored lining extending into your esophagus. In your stomach, IM looks like abnormal patches. The endoscopist will take a biopsy of the abnormal tissue to confirm their suspicion. If you have a history of chronic gastritis or acid reflux, your healthcare provider may order an upper endoscopy to check for IM.

Your healthcare provider will offer you medication before the exam to help you relax and numb your throat. Then they will pass a long, thin, flexible tube with a camera and a light at the tip, down your throat, through your esophagus, into your stomach and the first part of your small intestine (the duodenum). This tube is called an endoscope. The camera will display the insides of your upper digestive tract on a screen for your healthcare provider to examine. The whole process, including sedation, takes about 30 minutes.

Healthcare providers treat the condition by attempting to eliminate the irritants that cause it. By these means, they hope to at least prevent metaplasia from progressing. Quitting smoking and drinking alcohol, treating acid reflux and eradicating H. pylori infection gives your tissues a chance to recover from the chronic inflammation that triggers metaplasia. If metaplasia progresses to dysplasia, healthcare providers may recommend removing the affected tissue to prevent it from progressing to cancer.

Advertisement

In theory, by catching it early enough and eliminating irritants completely, metaplasia could be reversible over time. However, studies have not conclusively shown this to be successful so far. The only known way to eliminate intestinal metaplasia is to remove the affected tissue. Even then, metaplasia sometimes reappears. This might be because it’s difficult to find all of the affected tissue to remove, or it might be because the programming of the cells has permanently changed. Long-term studies following treatment are needed to resolve this mystery.

Your healthcare provider will want to keep it under observation. While most cases won’t progress all the way to cancer, you will want to intervene well before that. In the meantime, your healthcare provider will focus on treating the causes of IM. This will usually involve lifestyle changes for you.

IM develops over a long period of chronic inflammation. You can significantly reduce your risk by working to reduce irritation to your stomach and esophagus over time by:

Follow your healthcare provider’s guidance, including lifestyle changes and regular screenings to ensure IM doesn’t progress.

At your appointment, you can ask:

Intestinal metaplasia of the stomach or esophagus is a sign of injury. It may or may not be reversible. While it might not cause symptoms on its own, it indicates that significant damage has already been done. It’s also a warning that more serious damage could result if the injury doesn’t stop. Even though the chance of cancer is small, it’s important to take this warning seriously and try to reduce or eliminate what's injuring your stomach or esophagus. Given the chance, partial or complete healing may be possible, and worse outcomes can be avoided.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

If you have issues with your digestive system, you need a team of experts you can trust. Our gastroenterology specialists at Cleveland Clinic can help.