Cleft lip and cleft palate are separations in the upper lip and mouth that occur while a fetus develops in the uterus. Treating cleft lip and palate involves surgery and may include speech therapy and dental work. Your child’s medical care team is there to support you each step of the way.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/10947-cleft-lip-cleft-palate)

A cleft lip and cleft palate are openings in a baby’s upper lip or roof of their mouth (palate). They’re congenital abnormalities (birth defects) that form while a fetus develops in the uterus. Cleft lips and cleft palates happen when tissues of the upper lip and roof of the mouth don’t join together properly during fetal development. Surgery can repair a cleft lip and/or cleft palate.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Our lips form between weeks four and seven of fetal development. Tissues from each side of the head join together at the center of the face to make the lips and mouth. A cleft lip happens when the tissues that make the lips don’t join completely.

As a result, an opening or gap forms between the two sides of the upper lip. The cleft can range from a small indentation to a large gap that reaches the nose. This separation can include the gums or the palate (roof of the mouth).

The roof of your mouth (palate) forms between six and nine weeks of pregnancy. A cleft palate is a split or opening in the roof of your mouth that forms during fetal development. A cleft palate can include the hard palate (the bony front portion of the roof of the mouth) and/or the soft palate (the soft back portion of the roof of the mouth).

Cleft lip and cleft palate can occur on one or both sides of the mouth. Because the lip and the palate develop separately, it’s possible to have a:

Cleft lip and cleft palate are common congenital disorders in the U.S.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention:

Advertisement

Cleft lip (either with or without a cleft palate) is more common in male babies. Cleft palate (without a cleft lip) is more common in female babies.

In most cases, there’s no known cause of cleft lip or cleft palate, and parents can’t prevent it. Most scientists believe a combination of genetic (inherited) and environmental (related to the natural world) factors cause clefts. There seems to be a greater chance of a newborn having a cleft if a sibling, parent or other relative has one.

You may have a greater chance of having a baby with cleft lip/cleft palate if you take certain medications during pregnancy, including:

Other factors (related to the birthing mother) that can contribute to the development of a cleft include:

Some studies suggest cleft lips and cleft palates have a genetic component. If you or your partner were born with a cleft lip or palate, your chance of having a baby with a cleft is around 2% to 8%. If you’ve already had a child with a cleft lip or palate, your chances of having another child with the condition are slightly higher.

Babies born with a cleft lip or cleft palate may have difficulties eating (both from the breast and a bottle). They may also have trouble speaking, and they often have fluid behind their eardrum that can affect their hearing. Some also have issues with their teeth.

Prenatal ultrasound can diagnose most clefts of the lip because these clefts cause physical changes in the fetus’s face. Isolated cleft palate (with no cleft lip present) is harder to detect this way. Only 7% of these appear on a prenatal ultrasound.

If an ultrasound doesn’t detect a cleft before birth, a physical exam of the mouth, nose and palate can diagnose cleft lip or cleft palate after birth.

In some cases, your provider may recommend amniocentesis to check for associated genetic conditions. Amniocentesis is a procedure to remove amniotic fluid from the amniotic sac.

Most healthcare providers detect cleft lip at your 20-week ultrasound (anatomy scan), which occurs between 18 and 22 weeks of pregnancy. Providers may discover it as early as 12 weeks. It’s more challenging to detect cleft palate on an ultrasound.

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/10947-cleft-lip-chart)

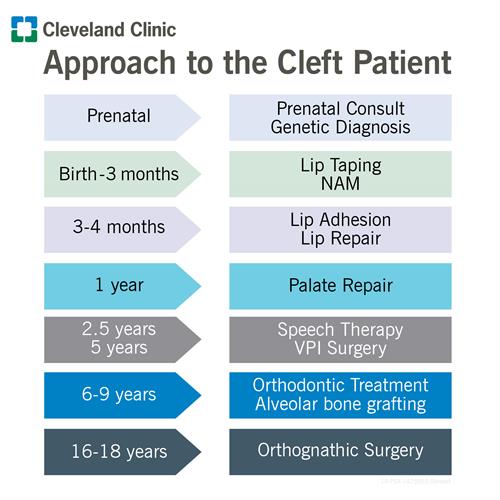

Surgery treats cleft lip and/or cleft palate. The exact details of treatment depend on the extent of the cleft, your child’s age and other special needs or health conditions. Your child will have surgery at a hospital, under general anesthesia, so they’ll be asleep during the procedure.

A cleft lip repair may require one or two surgeries. The first surgery usually occurs when your baby is between 3 and 6 months old. This surgery closes their lip. The second surgery, if necessary, is usually done when your child is 6 months old.

Several techniques can improve the outcomes of cleft lip and palate repairs when used appropriately before surgery. They’re noninvasive and can dramatically change the shape of your baby’s lip, nose and mouth. For example:

Cleft palate surgery usually occurs when your baby is 12 months old. It creates a working palate and reduces the chances that fluid will develop in your baby’s middle ears. To prevent fluid buildup, children with cleft palate usually need special tubes placed in their eardrums to help drain fluid. Their healthcare providers will check their hearing once a year.

Advertisement

Up to 40% of children with a cleft palate will need further surgeries to help improve their speech. A speech pathologist will assess your child’s speech between the ages of 4 and 5. They may use a nasopharyngeal scope to check the movement of their palate and throat. If your child needs surgery to improve their speech, it usually occurs around age 5.

Children with a cleft involving the gum line may also need a bone graft when they’re between the ages of 6 and 10. This procedure fills in the upper gum line so that it can support permanent teeth and stabilize the upper jaw. Once the permanent teeth grow in, a child will often need braces to straighten their teeth and a palate expander to widen their palate.

Your child may need additional surgeries to:

Possible risks of surgery include bleeding, infection and damage to nerves, tissues or other structures. Cleft lip and cleft palate surgery is usually successful, and risks are low. Cleft lip surgery leaves a small pink scar that should become less noticeable as your child grows.

Children often need treatment beyond surgery for cleft lip or palate. Some other treatments their healthcare providers may recommend are speech therapy and orthodontic treatment.

Advertisement

Because of the number of oral health and medical problems associated with a cleft lip or cleft palate, it takes a team of healthcare providers working together to develop a comprehensive care plan. Your child’s treatment usually begins in infancy and often continues through their early adulthood.

Members of their healthcare team may include:

Treatment may take many years and require several surgeries. But most children affected by these conditions have a normal childhood. Treatment helps improve speech and feeding issues. Some people may be self-conscious about the shape of their lips or scarring. Talk to your child’s healthcare providers about how you can offer support over the years.

You can’t prevent your baby from having cleft lip/cleft palate. However, you may be able to lower the risk by not using cigarettes, alcohol and certain medications during pregnancy. Talk to your healthcare provider to learn more.

It’s possible to breastfeed your baby if they have cleft lip and/or cleft palate. But you’ll need support from trained healthcare providers. Breastfeeding success depends on many factors, including:

Babies use suction to latch onto the breast and remove milk. Cleft lip and/or cleft palate can interfere with your baby’s ability to use suction in this way.

Research shows that some babies who only have cleft lip can create enough suction to breastfeed successfully. Babies with small clefts affecting only their soft palate may also create the necessary suction.

However, creating suction is typically harder for babies:

These babies may struggle to create suction because there’s not enough separation between the inside of their nose and the inside of their mouth.

If your baby can’t suction well, the effort of trying can make them very tired. They may also experience nasal regurgitation or reflux. Some babies can’t remove enough milk, and this can lead to problems with nutrition and growth.

The first thing to know is that you’re not alone. Many families are in your shoes and wondering how they’ll manage breastfeeding or alternative options.

Thankfully, lactation support providers — including lactation consultants and breastfeeding medicine specialists — are prepared to help you find ways to breastfeed your baby. These providers can also help you if breastfeeding isn’t possible. Set up an appointment as early as you can, even while you’re still pregnant, to begin learning how to care for your baby and what you can expect.

A lactation support provider can help you:

It’s important to know that despite everyone’s best efforts, it may not be possible to feed your baby directly from your breast. This might be the case even after surgical repair. However, your lactation support provider can still help you find other ways to feed and bond with your baby.

For example, your provider can help you with breast milk feeding. This involves removing breast milk (by hand or pump) and giving it to your baby with a spoon, cup, bottle or syringe. Some bottles are specially designed for babies who need a little extra help with suckling. Your provider will guide you on which bottles to choose.

Breast milk feeding allows your baby to get the important nutrition that your milk provides. Breast milk may also lower your baby’s risk of getting ear infections, which are common among babies with cleft lip/cleft palate.

Your provider might also encourage you to hold your baby to your chest and try breastfeeding, even if your baby can’t remove enough milk for nourishment. Doing so may help you keep your milk supply. It’s also an important way to soothe and bond with your baby.

Generally, children with clefts have the same dental needs as other children. However, children with cleft lip and palate may also have missing, misshapen or poorly positioned teeth. Some recommendations include:

Problems with eating, hearing and speech are common in children with clefts. Children may also have issues with their teeth or self-esteem.

With a separation or opening in the palate, food and liquids can pass from your child’s mouth back through their nose. Some babies have difficulty breastfeeding or taking a bottle because they can’t create enough suction.

Children with cleft palate are more prone to fluid buildup in their middle ears (glue ear). If left untreated, this causes hearing loss.

Children with cleft palate may have trouble speaking. Their voices may not carry well, and their speech may be difficult to understand. Not all children have these problems, and surgery may solve them.

Children with clefts are prone to dental problems like cavities and missing, malformed or displaced teeth.

They may be more prone to defects of the alveolar ridge, the bony upper gum that contains the teeth. A defect in the alveolus can:

Children with clefts may be self-conscious or embarrassed about their appearance, even at a young age. This can cause emotional, social or behavioral problems at school and lead to issues with their confidence.

Whether you learned about this condition during a prenatal ultrasound or after delivery, a cleft lip or palate can raise many concerns that may be hard to put into words. You might worry about the surgeries your baby will need, how they’ll recover or what their childhood will be like. Know that your baby’s care team is there for everyone in your family (including you). Don’t hesitate to share all your questions and concerns so you can get the information you need to feel more comfortable with the road ahead.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic's health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability, and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic's health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability, and up-to-date clinical standards.

When your child is born with a cleft palate, you may wonder about their future. Cleveland Clinic Children’s offers personalized treatment to help them move forward.