Your occipital lobe, the smallest and rear-most of the lobes, is the visual processing hub of your brain. This area processes visual signals and works cooperatively with many other brain areas. It plays a crucial role in language and reading, storing memories, recognizing familiar places and faces, and much more.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/24498-occipital-lobe)

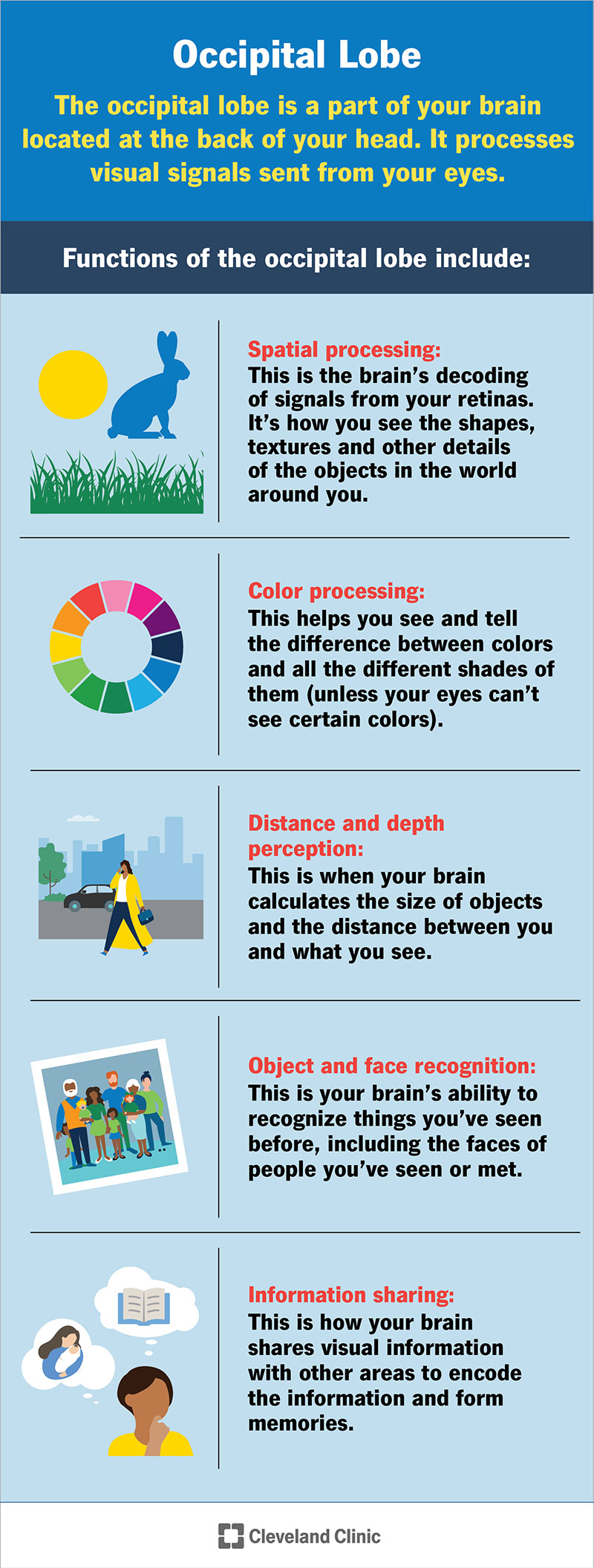

The occipital lobe is a part of your brain located at the back of your head. Though it’s the smallest lobe of your brain, it’s still extremely important. That’s because the occipital lobe processes visual signals sent from your eyes.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

The pupils of your eyes are like windows, allowing light from the world in front of them to enter your eye. Inside, at the back of each eye, is a patch of incredibly sophisticated cells known as the retina. Your retinal cells take what you see and turn those images into a kind of highly detailed coded message.

The coded messages travel along your optic nerves toward your brain and then travel within your brain optic tracts. Along the optic tracts, areas of your brain, like the thalamus, relay the coded signals until they reach your occipital lobe. The main job of your occipital lobe is decoding the messages sent from your eyes and turning that information into forms the rest of your brain can use.

That job happens in two specific areas in your occipital lobe: the primary visual cortex and the secondary visual cortex. The term “cortex” comes from the Latin word for “tree bark,” and it describes the wrinkly-textured outer surface of your brain. The visual cortices (the plural of “cortex”) are parts of the cortex that process vision-related signals.

Everything your eyes can do falls under the term “vision,” but that actually involves several different processes and capabilities. Those include:

Advertisement

Your eyes detect what’s visible in the world around you and turn that information into signals that then travel to your brain. However, the occipital lobe is what takes those signals, processes them and then works cooperatively with other parts of your brain to use what you see.

One of the most important examples of this is reading. Your occipital lobe recognizes writing, and then it works with a part of your brain’s temporal lobe to recognize the written shapes and symbols. The temporal lobe then understands them as written language and processes the content.

Your occipital lobe is at the very back of your skull. It’s just inside your skull, right above the hollow at the back of your head. Like all lobes of your brain, your occipital lobe has a left and right side, with a groove dividing it into the left and right sides.

Your occipital lobe is the smallest of the lobes of your brain. The average occipital lobe makes up between 10% and 18% of your brain’s volume (there’s uncertainty because experts disagree on exactly the exact borders that separate the lobes from their neighbors).

Your occipital lobe is made up of the same cells that make up every other area of your brain. The basic cell types include:

Advertisement

For those who have blindness, their occipital lobe is still active. The type of activity in that lobe depends on if a person was born with blindness or developed it very early in life, or if they developed it later on.

In those with early or congenital blindness, their occipital lobe is still very active. However, that activity happens when they use their other senses, such as smell, hearing and touch. The occipital lobe of a person with blindness also becomes more active when they’re speaking or listening to others talking.

This reassignment of the occipital lobe is a form of neuroplasticity. That’s the term for the brain’s ability to adapt itself to an unusual circumstance or condition.

People who develop eye-based blindness later in life have a visual cortex that once handled visual information. While it may no longer receive as much (or any) vision-based input, it still responds similarly to input from other senses.

Two key ways this happens are with the senses of hearing or touch. In effect, your brain redirects its visual processing abilities to other senses. That allows a person to “see” an object by feeling it, or to form a mental image of their surroundings based on what they can hear.

Advertisement

Any condition that can affect your brain tissue can affect your occipital lobe. Examples include:

Because your occipital lobe’s jobs all revolve around your vision, the symptoms of conditions that affect it are all vision-related. Examples of these symptoms (with more about them below) include:

Damage to your occipital lobe can cause you to lose part or all of your field of vision. It can affect one eye at a time or both eyes. When loss is total and affects both eyes, it’s known as cortical (cortex-related) blindness. If you have this, your brain can’t process vision-related nerve signals — even though your eyes are working correctly — causing you to experience blindness.

Advertisement

Damage to your brain can disrupt your brain’s self-monitoring processes, preventing you from recognizing symptoms or other signs of a problem. The most common form of visual anosognosia is when a person who has blindness denies that they have a vision issue. A rarer form of Anton syndrome is when a person believes they’re blind but shows signs that their vision still works (at least on an unconscious level).

These are when your brain can’t properly process what you see. The effect is similar to trying to open a file on your computer, but not having the right program to do so. Your computer can’t open it because it doesn’t know how to use the file. Likewise, visual agnosias mean your brain can’t process what your eyes see. However, other senses can sometimes help you compensate for this.

Examples of this include:

These are when there are distortions or changes in your vision that happen because your brain isn’t processing signals from your eyes correctly. That can affect any of the following characteristics of what you see:

Under ordinary circumstances, a person’s vision happens because their brain is processing signals sent by their eyes. Once the signals reach your occipital lobe, neurons in that part of your brain send and relay signals to other areas in your brain. Visual hallucinations are when neurons in the occipital lobe act as if they’re processing signals from your eyes, but in reality, they’re acting on their own without such signals.

There are many ways that healthcare providers can check the health of your occipital lobe. These include diagnostic tests, lab tests, imaging scans and more. Examples include:

Many conditions can affect your brain tissue, and the treatments for those conditions can vary widely. Treatments that work for one condition may not affect other conditions or might make other conditions much worse. A healthcare provider is the best person to tell you about available treatments for any brain-related condition. They’ll evaluate your medical history, circumstances, preferences and other factors to provide relevant answers for your situation.

There are many things you can do to maintain the health of your entire brain, including your occipital lobe. Some brain-related conditions are preventable. Others may not be, but you might be able to reduce the risk of them happening. Some of the most important things you can do include:

Your occipital lobe is the smallest lobe of your brain, but it’s one that most people rely on heavily. This part of your brain, found at the back of your head, processes signals from your eyes. Many conditions and disorders can affect it, but scientific and medical understanding of this brain area offers hope for diagnosing and treating many of these concerns.

Your occipital lobe also connects with many other parts of your brain, linking vision to many other abilities. It’s a key part of sensing and perceiving the world around you, and it sends information about your experience to different parts of your brain to form memories. Even though the occipital lobe is at the back of everyone’s mind — literally and figuratively — this part of your brain is one of the most important contributors to your everyday life.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

If you have a neurological condition, you want expert advice. At Cleveland Clinic, we’ll work to create a treatment plan that’s right for you.