Neuroblastoma is cancer that develops in a child’s nerve tissue. The main symptom is a lump that you can feel under your child’s skin, usually in their belly, neck or chest. Other symptoms can vary widely but include swollen lymph nodes, bone pain and dark circles around your child’s eyes. Treatment can sometimes cure this cancer.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/14390-neuroblastoma.jpg)

Neuroblastoma is a type of cancer that can affect babies and young children. “Neuro” refers to nerves, and “blastoma” is the medical word for cancer that begins in immature cells. Neuroblastoma grows in immature nerve cells called neuroblasts. This cancer specifically affects neuroblasts in your child’s sympathetic nervous system.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Neuroblastoma usually starts in nerve cells in your child’s adrenal glands. These glands are located in your child’s upper belly (abdomen), just above their kidneys. But neuroblastoma can start in other nerve cells, too — usually those located elsewhere in your child’s belly or in their chest or neck.

Once the initial tumor forms, its cancer cells can spread (metastasize) to other parts of your child’s body, including their:

Neuroblastoma almost always develops before age 5. The average age at diagnosis is 1 to 2 years. Around 700 to 800 children receive a neuroblastoma diagnosis each year in the U.S. Providers rarely diagnose neuroblastoma in children over age 10 or adults.

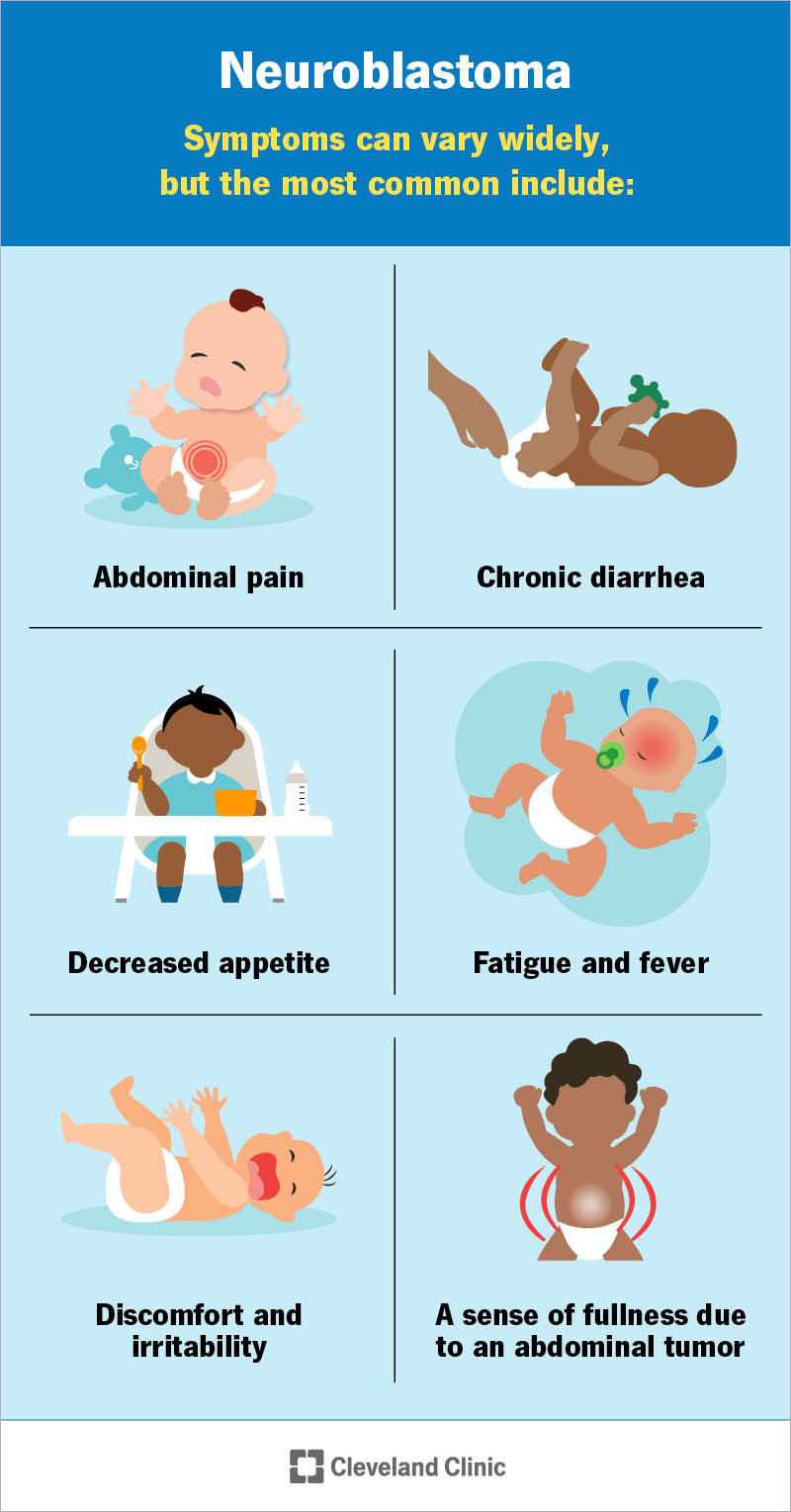

Neuroblastoma has many possible signs and symptoms. These can vary based on:

A lump is the most common sign parents or caregivers notice. You might feel the lump in your child’s belly area, neck or chest. The lump might feel hard to the touch. If you press on it, your child likely won’t feel any pain.

Advertisement

Tumors may press on nearby structures inside your child’s body, like their windpipe, esophagus, nerves, blood vessels or lymph vessels. This can lead to a wide range of neuroblastoma signs and symptoms, such as:

If tumors spread to nearby tissues (like lymph nodes) or farther away, signs and symptoms might include:

If the tumors release hormones, your child may experience:

Experts don’t fully understand what causes neuroblastoma. They do know this type of cancer occurs when immature nerve cells (neuroblasts) keep growing and dividing when they shouldn’t. These abnormal cells build up and form a tumor. But experts are still trying to figure out what causes this process to start in the first place. They believe gene mutations likely play a role.

Gene mutations are changes to your child’s genes that affect how they work. Certain genes help cells in your child’s body grow and divide normally. Other genes prevent cells from growing out of control or fix mistakes that happen when cells divide.

Any changes to those genes can keep them from doing their jobs. Experts believe certain gene mutations may happen during fetal development or soon after birth that allow some neuroblasts to grow out of control.

In the vast majority of cases, the gene changes happen randomly. Experts haven’t found any specific chemicals or exposures that raise a person’s risk of having a baby with neuroblastoma.

Rarely, neuroblastoma runs in families. About 1 or 2 out of every 100 children with neuroblastoma inherit the gene change from a biological parent. Providers call this hereditary or familial neuroblastoma.

Advertisement

No matter the exact cause, it’s not your fault that your child has neuroblastoma. Experts haven’t identified any ways to prevent the condition, and there’s nothing you can or should have done differently.

Children with hereditary neuroblastoma typically have changes to one of these genes:

Experts continue to look into which gene mutations might occur in nonhereditary forms of neuroblastoma.

Some genes within tumor cells affect how the cancer progresses. For example:

Changes in the tumor cells’ chromosomes also matter. Chromosomes are threadlike structures in cells that are made of proteins and DNA. Experts can examine:

Advertisement

This information helps experts define how aggressive the tumor is and what risk category your child will be placed in.

Healthcare providers diagnose neuroblastoma by doing physical exams and running tests. During the physical exam, your child’s provider will:

Providers can learn a lot from the physical exam. If they think your child may have neuroblastoma, they’ll run tests to confirm a diagnosis and see if the cancer has spread. Possible tests include:

Advertisement

Providers may give your child anesthesia so they’re asleep during certain tests, like:

This makes the tests easier for the providers to do, and your child won’t feel any discomfort.

Healthcare providers classify neuroblastoma based on how advanced the cancer is and how fast it’s growing. They also consider whether it has spread (metastasized) to other parts of your child’s body.

The stages of neuroblastoma include:

Testing helps providers identify the stage of neuroblastoma for your child. Then, they use the stage and other information to identify the risk group.

Risk groups describe the chances of a tumor responding to treatment. Knowing the risk group helps providers plan the most effective treatment for your child.

The three risk groups are:

Your child might need multiple and more aggressive treatments if they have high-risk neuroblastoma. Treatment may be more conservative if they have low-risk neuroblastoma.

Your child’s care team will assign a risk group based on:

Neuroblastoma treatment depends on your child’s risk group. Your child may need one or more of the following:

Your child’s care team will include a pediatric oncologist, as well as many other specialists. They’ll explain which treatments are necessary and the best timing for them. They’ll also explain the benefits and risks and what you can expect as your child recovers from treatment.

Clinical trials may be an option for your child. Your child’s care team can tell you more about possible trials and what they involve.

Treatment can often cure low-risk and intermediate-risk neuroblastomas, and some high-risk neuroblastomas. But each child is different, and it’s hard to predict treatment outcomes. Your child’s healthcare team can give you a better idea of what to expect.

Here are some questions that may help you learn more about your child’s condition:

Your child’s care team can give you the most accurate picture of how neuroblastoma may affect your child’s health and lifespan. They have detailed knowledge about the tumors and their likelihood of responding to treatment.

In general, providers use the neuroblastoma risk groups (low, intermediate or high) to plan treatment and develop a prognosis. The lower the risk group, the better the chances of a good prognosis.

The five-year survival rate for neuroblastoma varies by risk group. Here’s what researchers have found as of 2025:

Remember that numbers only tell part of the story. Your child’s care team will tell you more about what you might expect based on your child’s unique medical history and how they respond to treatment.

If you’ve just learned your child has neuroblastoma, you might feel all sorts of things — shock, fear, confusion. Know that all of your emotions are valid. Lean on your child’s care team to explain next steps. They’ll help you understand your child’s exact diagnosis and which treatments are available to help.

And remember — you’re not alone. There are many others who’ve walked a similar path or are walking it now. Talk to your child’s providers about how to connect with support groups. Sharing your experiences with other parents and hearing stories of hope can give you strength.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic's health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability, and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic's health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability, and up-to-date clinical standards.

Hearing your child has a cancer called neuroblastoma can instantly change your world. Cleveland Clinic Children’s is here with the treatment and support you need.