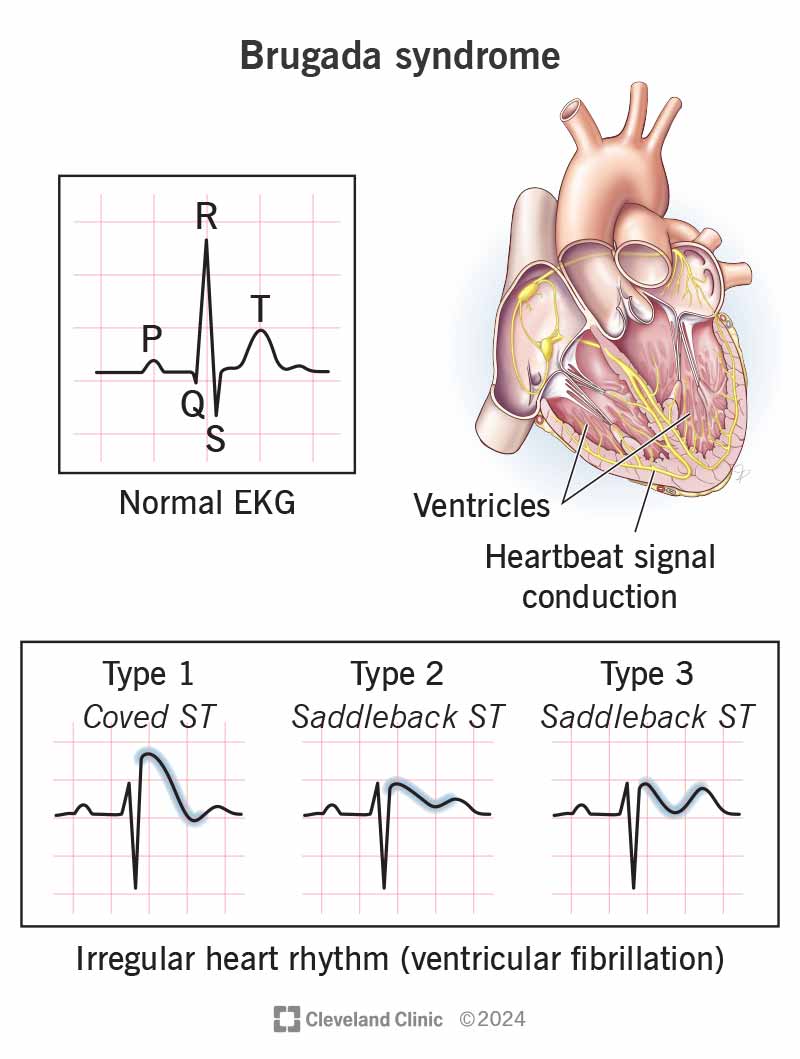

Brugada syndrome is a rare heart condition that can make your heart’s lower chambers (ventricles) beat in an abnormal rhythm. This can make you faint or have a cardiac arrest, putting you at risk of sudden cardiac death. Some people inherit this condition from a parent, but many others don’t know the cause.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/brugada-syndrome)

Brugada syndrome is a disease that can cause an abnormal rhythm in your heart’s lower chambers (ventricles). This irregular heart rhythm, ventricular fibrillation (v-fib), prevents your heart from pumping blood to your brain. When this happens, you faint.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

V-fib can lead to sudden cardiac death. This often happens while you’re at rest or asleep. Out of all the sudden cardiac deaths that happen, researchers blame Brugada syndrome for 4% of them.

Brugada syndrome is rare. About 3 to 5 people in 10,000 have the condition.

Brugada syndrome symptoms can happen at any age, but often start when you’re around 40 years old. Symptoms may include:

More than 70% of people with Brugada syndrome don’t have any symptoms.

A fever can trigger Brugada symptoms. This is why people with Brugada syndrome need to treat a fever right away — even if they have an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD). You can take over-the-counter (OTC) medicines to bring your fever down.

Other symptom triggers include:

Advertisement

Brugada syndrome causes include an unknown cause or a genetic one. About 70% of people with Brugada syndrome don’t have a known genetic mutation.

Some people have a genetic variation in one of 18 or more genes, most often in SCN5A. These variations interfere with heartbeat signal conduction in your heart.

It only takes one copy of an affected gene from one parent to inherit Brugada syndrome. Any child of someone with a Brugada-related gene variation has a 50% chance of having it, too.

Brugada syndrome is more common in men. They’re 8 to 10 times more likely than women to have the condition. Anyone with a biological family history of sudden cardiac death or Brugada syndrome should find out if they have the disease.

The condition also appears to be more common in people with Asian ancestors.

To make a Brugada syndrome diagnosis, a healthcare provider will:

Tests for diagnosing Brugada syndrome include:

Based on your EKG results, you may also have:

The goal of Brugada syndrome treatment is to keep you from having ventricular arrhythmias and treat them when they happen.

Your treatment may include:

If you’re not having symptoms, your provider may decide you need an ICD because of your family history or test results. Some providers may do frequent follow-ups and only treat you when you have symptoms. Others don’t agree with this approach because your first symptom could be sudden cardiac death.

ICDs aren’t perfect devices. They can:

Advertisement

You can do many activities a few days after receiving an ICD, but you’ll likely wait a week to drive. You can get a little physical activity every day, but not to the point of tiring yourself out. Don’t do any heavy lifting or strenuous activities until your provider tells you it’s OK.

There’s no cure for Brugada syndrome. But treatments can lower your risk for sudden cardiac death, which is a complication of Brugada syndrome.

People with Brugada syndrome who have symptoms but aren’t receiving treatment have a high risk of sudden cardiac death. People without symptoms and with a normal EKG have a much lower risk of sudden cardiac death.

If you inherited Brugada syndrome from a parent, you can’t change that. If you know Brugada syndrome is in your family, you and your relatives can get a genetic test to check for it. Also, if you’re considering pregnancy, you can see a genetic counselor to find out if you’re at risk of passing it on to your children.

If a provider diagnosed you with Brugada syndrome, avoid the things that trigger an arrhythmia. You can prevent symptoms by avoiding fever and certain medications and substances. Ask your provider for a list of medicines to avoid.

You should have an appointment with your provider at least once a year. If you have an ICD, your provider should check your device at least twice a year. Tell your provider about anything unusual.

Advertisement

You need immediate medical care if you’re in cardiac arrest. Since you won’t be able to call for help yourself if this happens, someone near you will need to help. If you’re at risk of cardiac arrest, ask your family to get CPR training and call 911 or a local emergency number. You can also let coworkers know about your risk in case you need their help.

Ask your provider:

It’s not easy to hear that you have a condition that may cause a cardiac arrest. But knowing you’re at risk allows you to take action to reduce that risk. Your healthcare provider can find the best treatment for you. It may give you peace of mind to have an automatic external defibrillator (AED) in your home and/or your child’s school. Also, ask people who live or work with you to learn CPR.

Advertisement

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

When your heart needs some help, the cardiology experts at Cleveland Clinic are here for you. We diagnose and treat the full spectrum of cardiovascular diseases.