Uterus transplantation is a recent medical innovation that can make pregnancy possible for people with absolute uterine factor infertility (AUFI). Uterus donors can be living or deceased. The transplantation is an extensive process that involves more than just surgery.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/uterus-transplant)

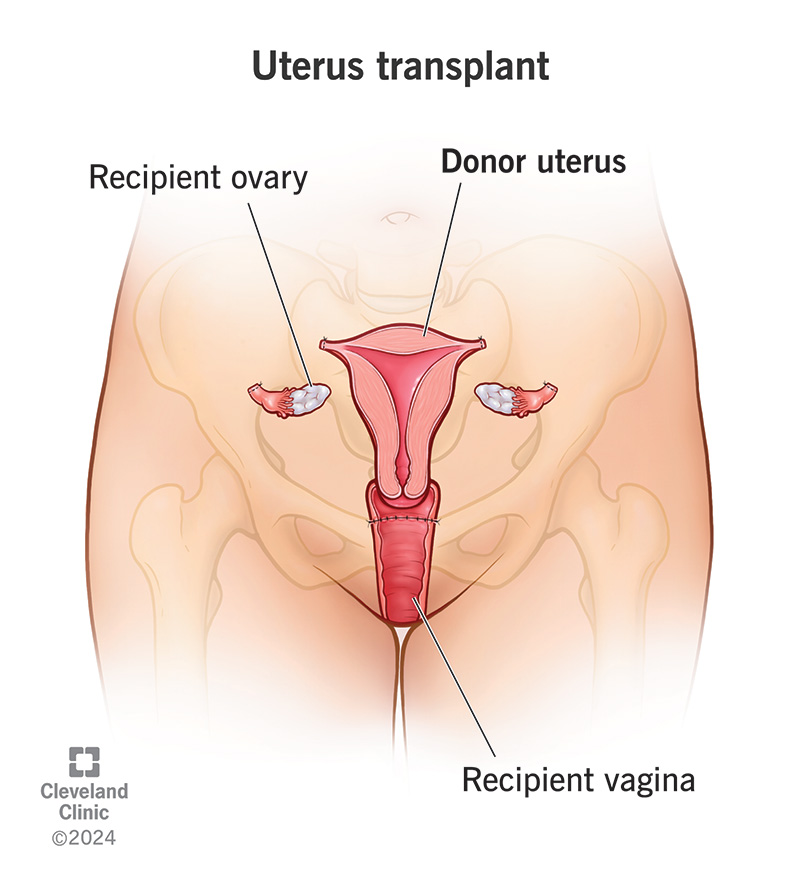

A uterus transplant involves removing a uterus from a donor and transferring it to someone who has absolute uterine factor infertility (AUFI). AUFI is a condition in which you’re unable to get pregnant because you don’t have a uterus or it isn’t functioning. A uterus transplant may make it possible for you to become pregnant if you have AUFI.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

If you have AUFI, it may feel like you don’t have control over your ability to build a family. A uterus transplant could give you an opportunity to take that control back. You may be able to redefine how AUFI affects your life.

Uterus transplantation is a complex process that involves much more than the transplant surgery. This is because the overarching goal is to have a live birth. In general, the intended process involves:

Uterus transplants are a recent — and uncommon — medical innovation. There have been over 100 uterus transplants performed worldwide, with over 70 live births. The first successful transplant was in 2011 in Sweden.

Two types of donors can give a person a uterus: living and deceased. The hospital doing your transplant may only accept certain types of donors. Your healthcare team matches you to a donor through blood type.

A living donor can be directed (known) or non-directed (anonymous).

Advertisement

A directed donor is often a biological family member (a mother or sister) who chooses to give their uterus. These are called directed donors because you know who they are. There’s often a clear connection between the person giving the organ and the person receiving it.

Anonymous donors (non-directed) are people who decide that they want to donate their uterus while alive. But they don’t have any one person in mind for their uterus.

In this case, the donor is someone who has died and previously expressed a wish to give their organs to others. The donor typically has no relationship with the recipient in this type of organ donation.

It can take several months or years of planning before the uterus transplant surgery happens. You’ll undergo an extensive screening process. This evaluation makes sure you’re physically, mentally and emotionally fit to go through every aspect of the transplantation.

You’ll meet with several specialists, including:

You’ll have a variety of medical tests and exams to check if you’re eligible for the transplant. This includes laboratory tests, imaging tests and psychological evaluations.

Not every hospital system does uterine transplants. And each hospital has its own criteria for who’s able to donate and receive a uterus. In general, criteria for receiving a uterus transplant may include:

Retrieving and implanting a uterus are both very complex surgeries. Whether you’re the donor or recipient, your healthcare team will go over the procedure in great detail. Don’t hesitate to ask questions.

If you’re donating your uterus, your surgeon will do the hysterectomy by a laparotomy, laparoscopy or robotics. A laparotomy is an open incision (cut) in your abdomen to access your uterus. Laparoscopy or robotic surgery typically involves five ports (access points) to remove your uterus.

Advertisement

Your surgeon also removes:

Before surgery, you’ll start taking medications to help make sure your immune system doesn’t attack the donor uterus (antirejection medications).

In general, during a uterus transplant surgery, your surgeons connect the donated uterus to your blood vessels. They also create a connection to your vagina.

They don’t connect your fallopian tubes to the transplanted uterus. This is why pregnancy can only happen with IVF after the transplant.

The surgery type is usually a laparotomy. This means your surgeon makes an incision in your abdomen to get to the space where the donor uterus will go. Some centers do the transplant robotically.

The surgery for transplanting a uterus usually takes six to eight hours. But this can vary.

Surgery to remove a uterus from a living donor typically takes up to 10 hours. It’s often longer than the surgery to transplant it. This is because the surgeons must be very careful to preserve all of the uterus. They also make sure not to damage surrounding tissues in the donor.

After the transplant surgery, your healthcare team will check you for signs of organ rejection or complications. The success of the surgery largely depends on if there’s proper blood supply to the uterus.

Advertisement

A few months after a successful transplant, you’ll start to have menstrual periods. Within three to 12 months of surgery, you’ll have an embryo transfer. Your healthcare provider will only implant one embryo at a time.

During pregnancy, you’ll continue to take antirejection medications. A team of maternal-fetal medicine (MFM) providers will monitor you and your pregnancy. You’ll also have cervical biopsies to check for organ rejection.

You’ll have your baby via a C-section. Vaginal delivery isn’t possible with uterus transplantation.

After birth, your healthcare team will continue to monitor you and your baby. Together, you’ll assess if you want to try for another pregnancy and if it’s safe to do so. Healthcare providers generally give a limit of two live births with a transplanted uterus.

A uterus transplant is meant to be temporary. Eventually, you’ll need a hysterectomy to remove the donated uterus. This may happen at the time of your C-section or a later date.

If the uterus becomes nonviable at any point during the process, a surgeon will need to remove it. Your healthcare team will also recommend removing the transplant if you have several unsuccessful embryo transfers or repeated miscarriages.

Advertisement

After the hysterectomy, you’ll stop taking antirejection medications.

If you have AUFI, uterus transplantation is the only way to try for pregnancy and childbirth.

Adoption and surrogacy are other options to build a family. Some uterus recipients saw the transplant process as an opportunity to play an active role in their future child’s health and well-being, according to one study. They viewed adoption and surrogacy as a more passive role.

The overall goal of uterus transplantation is to have a live birth. But there are many steps to get there. So, researchers define the success of a uterus transplant in different ways. The two main ways are if the transplant is viable (healthy) and if the transplant results in a live birth.

According to one study of uterus transplants in the U.S., 25 of 33 uterus transplants (76%) were successful. Under the study’s definition, this means that the uterus was viable 30 days after surgery.

At the time of that same study, 19 of 33 of those transplant recipients (58%) had a least one live birth.

There are risks and possible complications for both the living donor and recipient.

For a living donor, there are general surgical risks, like:

Complications specific to removing your uterus include injury to surrounding organs and structures. Urinary system issues are the most common complications. They include:

It’s also important to consider the potential mental and emotional tolls of donating your uterus. Some donors have expressed feeling intense guilt when the transplant wasn’t successful.

Risks and possible complications for the uterus transplant recipient include:

Your healthcare team will go over all the possible risks and complications in detail with you. Uterine transplant is a newer medical innovation. So, researchers don’t know the long-term health impacts of it.

It’s important to remember that a uterus transplant doesn’t guarantee a live birth. Pregnancy is very complex. Other factors could lead to implantation issues and miscarriages.

On average, it takes about three to six months for your transplanted uterus to heal after surgery.

For donors, it may take about four to six weeks to recover. Recovery depends on the type of hysterectomy method your surgeon uses.

There isn’t a national waiting list for uterus transplants in the U.S. like there is for other organs. But hospitals that do the procedure may have their own waiting list. Some hospitals do uterine transplants as part of clinical trials. Others have special programs dedicated to the procedure.

Yes, it’s possible to donate your uterus while you’re alive or once you’ve died. For living donation, there’s an extensive screening process to make sure the surgery is safe for you. You’ll also have to meet certain criteria to make sure your uterus will work for someone else.

The criteria vary from hospital to hospital. But in general, they may include:

You also have to go through a psychological evaluation.

Uterus donation isn’t for everyone. But if you’re interested in the possibility, reach out to a healthcare provider. They can provide resources on uterus donation.

The cost of a uterus transplant varies depending on if you’re part of a clinical trial or using a hospital program. In the U.S., uterus transplantation isn’t typically covered by health insurance. But insurance may cover parts of the process, like IVF and/or delivery of your baby.

Whatever your case, your healthcare team will go over how much you can expect to pay out of pocket for the entire process.

Uterus transplantation is a massive undertaking, physically, mentally and emotionally. But it may make the impossible possible if you have absolute uterine factor infertility (AUFI). If you’re interested in this potential, reach out to a healthcare provider to see if it’s an option for you.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic's health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability, and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic's health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability, and up-to-date clinical standards.

From routine pelvic exams to high-risk pregnancies, Cleveland Clinic’s Ob/Gyns are here for you at any point in life.