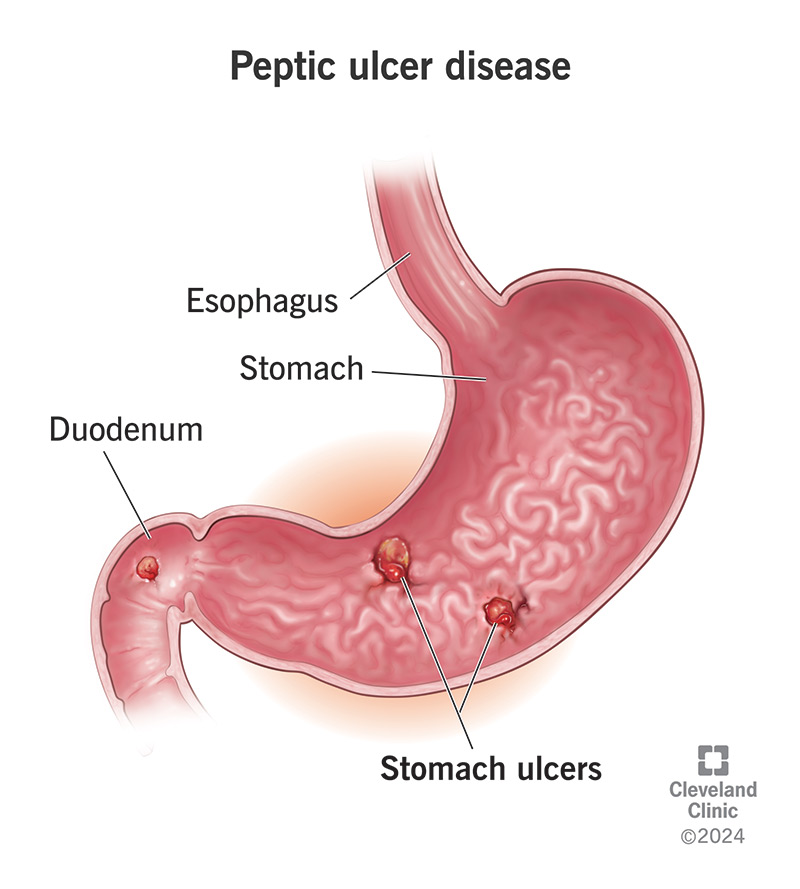

Peptic ulcer disease causes open sores in your stomach lining or duodenum (the top of your small intestine). Symptoms include burning or gnawing stomach pain. H. pylori infection and NSAIDs use are the most common causes. Treatment is with medications, unless you have complications like bleeding.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/Images/org/health/articles/10350-peptic-ulcer-disease.jpg)

Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) is a condition that causes ulcers (open sores) to develop in the lining of your digestive tract. The word “peptic” comes from pepsin, a digestive enzyme that your stomach produces. Pepsin and stomach acid help break down food for digestion. These substances are highly corrosive.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Normally, a strong mucous lining protects your digestive tract from these substances. But in peptic ulcer disease, this protection breaks down. Pepsin and acids eat into the lining, forming ulcers. Most ulcers form in your stomach or duodenum, where these substances are most active. But they can also occur elsewhere.

Peptic ulcers usually develop in your stomach or duodenum.

Rarely, they can appear in other parts of your digestive tract:

Up to 70% of people with peptic ulcer disease don’t notice symptoms. But the most common ones are central upper abdominal pain (epigastric pain) and indigestion. Indigestion often happens after eating and feels like a burning or gnawing sensation.

Other possible symptoms related to peptic ulcer disease include:

Advertisement

The mucous lining in your digestive tract protects it from acids and enzymes and helps repair damage, especially in your stomach and duodenum. PUD happens when something weakens these defenses.

It takes a long-term issue to lower these defenses enough for acid to erode the lining. Most cases are due to:

Less common causes of peptic ulcer disease include:

You can also get a peptic ulcer in your:

You have a higher risk if you have an H. pylori infection, take NSAIDs often, or both. Other things, like smoking, alcohol and certain medications, can contribute to your risk.

Without treatment, PUD can lead to:

Symptoms of these complications may include:

If your symptoms suggest an ulcer, your provider will examine you and test for H. pylori infection. This might mean a breath test or stool test.

Imaging tests like a CT scan or GI X-ray can spot large ulcers. Many people get a final diagnosis from an upper endoscopy. This also allows your provider to test for H. pylori directly.

Most peptic ulcers heal with medication. But if you have complications (like a bleeding or perforated ulcer), you may need more care. Many issues can be treated during an endoscopy.

Medications can reduce acid, protect your lining and treat infection. They include:

If you have a bleeding ulcer, your provider may treat it during endoscopy by cauterizing the wound or injecting medication. A perforation may need stitches.

Advertisement

Rarely, people need surgery for ulcers that don’t heal or that keep coming back. This can involve:

See a provider if you think you might have a peptic ulcer. Over-the-counter medications may ease pain, but they won’t fix the root cause.

Even if your symptoms are mild, untreated ulcers can get worse. H. pylori can also lead to other problems, like stomach cancer.

Get emergency care if you have:

They might, but only if the cause goes away. If you have H. pylori or another condition, you’ll need treatment. Even if NSAIDs were the cause and you’ve stopped taking them, you should still get checked to rule out infection.

Most peptic ulcers heal within a few weeks. Most people take medications for about two months. Treatment is usually effective, but people with chronic conditions may need long-term therapy.

Your healthcare provider may test again after treatment to make sure the ulcer has healed and the infection is gone. H. pylori can come back, and ulcers may return if the cause isn’t addressed.

Advertisement

Yes. The two most important things you can do are:

Foods don’t cause peptic ulcers, but some can make symptoms worse, especially spicy or acidic foods. Alcohol and smoking can also aggravate ulcers. Avoid these if you have symptoms or a history of peptic ulcer disease.

Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) means something has weakened your natural defenses against stomach acids and enzymes. This chemical change takes time to develop, and it usually needs treatment to reverse.

Peptic ulcers are common and treatable, but they can lead to serious complications if ignored. Even if symptoms are mild, don’t wait to talk to a healthcare provider.

Advertisement

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

When you have a stomach ulcer, it can feel like your body is attacking itself. Cleveland Clinic’s digestive experts can help with a custom treatment plan.