Pigment dispersion syndrome and pigmentary glaucoma are the same condition, but pigmentary glaucoma is a more advanced form. These conditions are similar to age-related glaucoma, but they start earlier and have different risk factors. With consistent monitoring, care and management, it’s rare for them to cause permanent blindness.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/pigment-dispersion-syndrome-pigmentary-glaucoma)

Pigmentary dispersion syndrome (PDS) is an uncommon eye condition that can cause early glaucoma. It happens when bits of the pigment in your iris break free and block fluid flow inside your eye.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

PDS and pigmentary glaucoma (PG) are the same disease but at different stages of development. PDS can turn into (the technical term is “convert”) PG, usually over several years or even decades. PDS doesn’t always become PG, but the risk of it doing so increases the longer it’s been since you got the diagnosis.

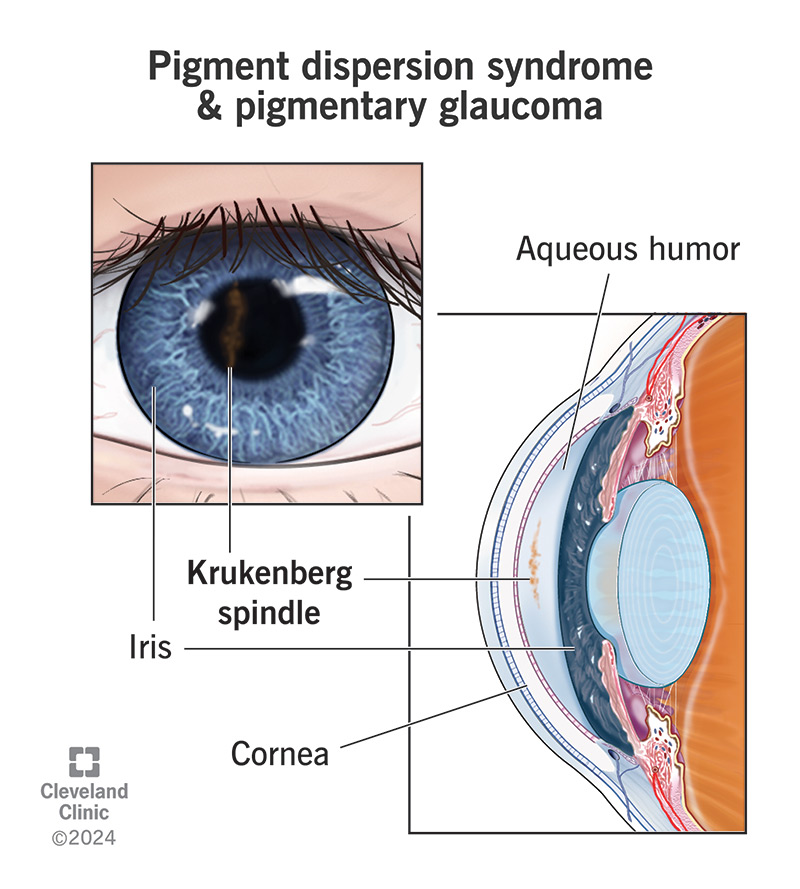

The iris of your eye is a flat ring of muscle that contains melanin, the pigment that gives your eyes their color. In front of and behind your iris are spaces filled with a fluid called aqueous humor. Pressure from the aqueous humor helps your eye hold its globe-like shape.

When you have PDS, your iris can’t hold its shape and dips back too far. That makes the back of your iris press against the muscle fibers that control your lens shape. As your iris widens or narrows, the iris rubs against those fibers and pigment granules in the iris wear away, like flakes of paint chipping away from a piece of wood.

Once those granules are loose and floating in the aqueous humor, the flow of fluid carries them to other places inside your eye. The aqueous humor has a drainage system, the trabecular meshwork, and granules can accumulate in that meshwork and damage it. When that happens, aqueous humor fluid can’t drain out of your eye properly, causing high pressure inside your eye (ocular hypertension) and eventually causing glaucoma. Without treatment, glaucoma causes irreversible, severe vision loss and blindness.

Advertisement

PDS often doesn’t cause symptoms, so many people don’t know they have it. When it does, they’re usually similar to the most common glaucoma symptoms. Those include:

Experts don’t fully understand what causes PDS, but there are several possible contributing factors. The factors researchers know most about include:

There are other reasons why pigment granules might break free from your iris. When there’s another cause for pigment displacement, that’s called “secondary PDS.” It’s different from “primary PDS,” which means PDS that doesn’t happen because of another condition. But secondary PDS can still lead to PG.

Some causes of secondary PDS include:

The most useful test for detecting PDS before it causes symptoms is a routine eye exam.

Some of the changes that PDS or PG can cause that show up on an eye exam include:

Advertisement

Several glaucoma tests can help with diagnosing PDS and PG. Some of these are common features of a routine eye exam, while others are a little more specific. Your eye specialist can tell you which tests they think will be the most helpful for diagnosing or ruling out PDS and PG.

These tests often include one or more of the following:

The treatments for PDS and PG are very similar to treatments for other forms of glaucoma. The treatments can involve one or more of the following:

In many cases, a combination approach may offer the best results for people with pigment dispersion syndrome and pigmentary glaucoma. An example would be combining medications with laser surgery. This works well when medication alone doesn’t lower pressure inside your eye as much as you need.

Advertisement

Your eye specialist is your best source of information about treatment approaches. Your provider can advise you on how treatments are likely to affect you, what your alternatives are and what kinds of side effects you can expect.

Not everyone who has PDS will have it lead to PG. But the risk of it doing so goes up over time. About 10% of people with PDS will develop PG within 10 years. That number rises to 15% after 15 years. The lifetime risk is between 35% and 50%.

Because PDS and PG usually start much earlier in life than other forms of glaucoma, it’s important to manage this condition as best you can. Part of that is seeing your eye specialist for regular follow-ups.

Those visits can happen every three to six months or yearly, depending on the details of your case. Follow-up visits allow your provider to detect pressure increases and recommend treatment to prevent damage or at least stop it from getting worse.

Ongoing monitoring and managing of your PDS or PG are key to keeping your eyesight. It’s rare for people who prioritize follow-up visits and manage their condition based on their specialist’s recommendations to have permanent blindness.

There’s nothing you can do to prevent PDS and PG. They happen unpredictably and people often don’t know they have these conditions until an eye specialist sees the changes during a routine eye exam or they start developing symptoms.

Advertisement

If you have PDS or PG, there are many ways you can help maintain your vision and prevent severe complications like vision loss.

Some eye symptoms mean you need medical attention quickly. Not getting treatment can lead to irreversible eye damage. You should talk to your eye specialist after your diagnosis to learn about the symptoms that are most relevant to your specific case and what you should do if you have any of these symptoms.

Symptoms that mean you need emergency medical attention include:

Some questions to ask your eye specialist include:

Learning you have pigment dispersion syndrome or pigmentary glaucoma may come as a shock, especially if you develop it at a younger age. While most types of glaucoma don’t happen until later in life, PDS and PG usually develop much earlier. These conditions work similarly to other forms of glaucoma, but there are key differences. And with routine monitoring and care, it’s possible to manage PDS and PG to limit or prevent more severe complications like vision loss or blindness.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Getting an annual eye exam at Cleveland Clinic can help you catch vision problems early and keep your eyes healthy for years to come.