Foraminal stenosis is a condition that happens when narrowing in parts of your spine causes compression of your spinal nerves. Most cases don’t cause symptoms, even with severe narrowing. However, when there are symptoms, pain and nerve-related issues can happen. There are many possible treatments, ranging from rest and physical therapy to surgery.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/24856-foraminal-stenosis)

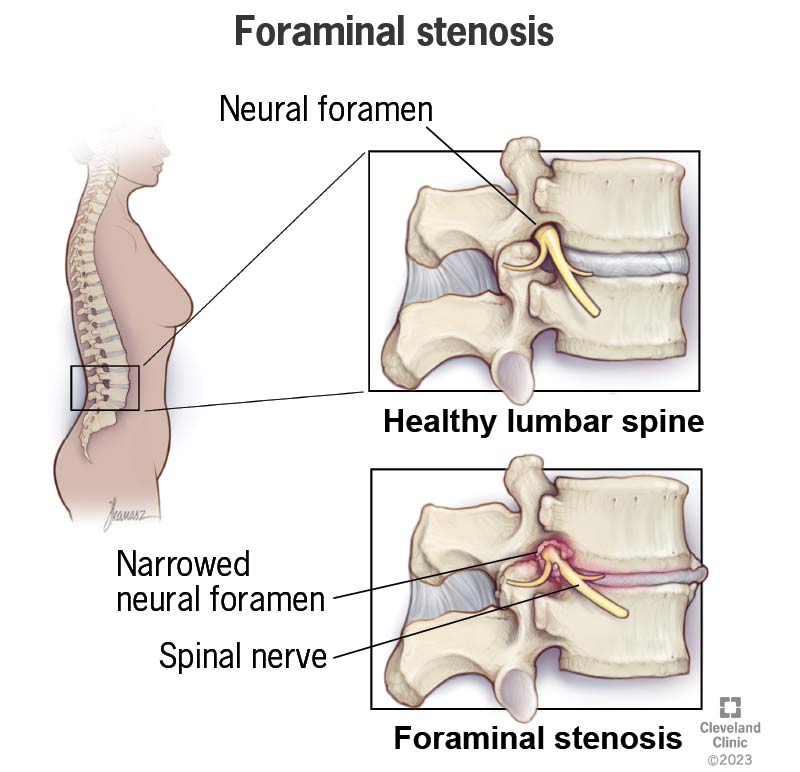

Foraminal stenosis is narrowing that happens in certain places around the nerves that come out of your spinal cord. It’s a type of spinal stenosis that affects the neural foramen, a series of openings on both sides of your spine.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Foraminal stenosis is like what happens to an electrical cord when you shut a door on it, wedging it between the door and frame. Eventually, the pressure on the cord can damage it, affecting how it conducts electricity. Likewise, foraminal stenosis can put pressure on affected nerves. Eventually, that can affect signals traveling through the nerve and cause nerve pain, and sometimes, permanent nerve damage.

A neural foramen is an opening where a spinal nerve exits your spine and branches out to other parts of your body. The size of the opening depends on where it is in your spine. The location of the foraminal stenosis also determines what type you have.

The different sections of your spine, from top to bottom, are as follows:

Data on how often foraminal stenosis happens is limited. It seems to be common, especially in people over age 55, and more likely to happen as people age.

Advertisement

Some studies indicate up to 40% of people have at least moderate foraminal stenosis in their lumbar spine by age 60. That increases to about 75% in people aged 80 and older.

However, most people with foraminal stenosis don’t know they have it, even when it’s severe. Only 17.5% of people with severe foraminal stenosis have symptoms.

Foraminal stenosis symptoms are similar to those of a pinched nerve or another form of radiculopathy.

Possible symptoms, listed from least to most severe, can include one or more of these:

The location of your symptoms is a key clue for diagnosing and treating foraminal stenosis. That’s because of the structure of your spinal cord and the spinal nerves that branch off it.

Your spinal cord is like a freeway, and your spinal nerves are entry and exit ramps. Nerve signals traveling to and from your brain have to use the correct ramp to reach their destination. When you have symptoms in a certain place, your provider can use the affected dermatome (area of your skin directly connected to the spinal nerve) to figure out — or at least, narrow down — where the issue is.

Some examples of symptom location and how they relate to the location of the narrowing are:

| Symptom location | Stenosis location |

|---|---|

| Thumb, index and middle finger. | Cervical spine (just below where your neck and upper back meet). |

| Upper abdomen, just below your breastbone (sternum). | Thoracic spine (between the lower half of your shoulder blades). |

| Outer edge of your foot, including your fourth and pinky toes. | Lower back, just above where your buttocks separate. |

| Symptom location | |

| Thumb, index and middle finger. | |

| Stenosis location | |

| Cervical spine (just below where your neck and upper back meet). | |

| Upper abdomen, just below your breastbone (sternum). | |

| Stenosis location | |

| Thoracic spine (between the lower half of your shoulder blades). | |

| Outer edge of your foot, including your fourth and pinky toes. | |

| Stenosis location | |

| Lower back, just above where your buttocks separate. |

When your symptoms happen is also a potential clue your healthcare provider might need. What you’re doing when you have symptoms can change whether or not the symptoms happen.

An example of this is lumbar foraminal stenosis. It tends to happen or get worse when you’re standing up and gets better when you sit down. Keeping track of your symptoms (such as writing down details of the symptoms when they happen) can help your provider diagnose and treat your condition.

There are many causes and contributing risk factors that can lead to foraminal stenosis. Some people can develop it with only one of these. For others, it can be a combination of more than one. Risk factors and possible causes include:

Advertisement

Complications of foraminal stenosis aren’t common, and serious complications are even rarer. When complications do happen, they can disrupt your life and routine activities. Some are serious and will need treatment to keep them from getting worse and causing other issues.

Some of the possible complications include:

A healthcare provider can diagnose foraminal stenosis based on your symptoms. They can also use magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to confirm their diagnosis. An MRI shows highly detailed images, allowing a healthcare provider to tell apart bones, nerves and muscles.

Many people don’t have symptoms even though they have foraminal stenosis that’s visible on MRI. That means an MRI is useful but not always necessary.

For people who can’t undergo an MRI, combining a computed tomography (CT) scan with a myelogram is usually the best option. This is especially helpful for people with implanted devices like pacemakers.

Advertisement

Other diagnostic tests that look for nerve-related problems may also help. Electromyography (EMG) and nerve conduction studies are examples of other common tests.

You might need other tests depending on your specific health history or needs. Your healthcare provider is the best person to tell you what other tests they recommend and why.

Foraminal stenosis may be treatable, and for some people, it’s possible to correct it. There are several treatment options. Some options may not be available to you, depending on your health history, the cause(s) of your foraminal stenosis and other factors. Your healthcare provider is the best person to tell you what treatment options are possible and which they recommend.

As long as you’re symptom-free, you probably don’t need treatment. Early symptoms like pain are often a reason to consider conservative treatments. Having complications like incontinence, weakness or paralysis is usually a sign that you need interventional treatments or surgery.

Treatments tend to come in three main types:

Conservative treatments are almost always the first approach with foraminal stenosis. They generally involve oral medications, changes to your activity and other noninvasive approaches.

Advertisement

Interventional treatments are a step up from conservative treatments. Injections of medications — like steroids — directly around the affected spinal nerve can sometimes help. These involve X-ray guidance to make sure the injection reaches the right spot. These injections may even delay your need for more direct treatments.

Most modern spinal decompression surgeries involve a minimally invasive approach. That means they use smaller cuts (incisions), reducing bleeding, pain and recovery time. Some of the possible surgeries include:

Because there are different types of treatment, the complications and side effects can vary greatly. Likewise, recovery time and what to expect after treatment can also differ from person to person. Your healthcare provider is the best person to tell you about possible or likely side effects that you may experience and what you should expect during your recovery.

Foraminal stenosis is a condition that can happen without symptoms. Some people learn they have it because it appears on an imaging scan they get for another reason. Others never know they have it.

Back pain may start before the nerve symptoms of foraminal stenosis. If you have back pain that lasts more than a few weeks, you should talk to a healthcare provider. They can help determine if your pain is foraminal stenosis or refer you to a specialist who can investigate further.

If you have more severe symptoms like tingling, numbness or muscle weakness — especially when these affect your arms or legs — you should make an appointment to see a healthcare provider as soon as possible. Foraminal stenosis severe enough to cause these symptoms can cause nerve damage and more serious complications.

Foraminal stenosis can be temporary or it can be longer-lasting. It’s most likely to be temporary when it happens because of short-term swelling and inflammation, such as from a minor injury that will heal on its own.

Foraminal stenosis is likely to be permanent when it happens with a chronic condition. It’s also likely to be permanent if it happens after a medical procedure or if it’s partly due to your spine’s natural shape and structure.

Most cases of foraminal stenosis never cause symptoms. Even severe stenosis only causes symptoms in about 17.5% of people. As long as you don’t have any symptoms of this condition, there’s little or no cause for concern (your healthcare provider can tell you which is true for you specifically).

When foraminal stenosis causes symptoms, the outlook can still vary. Minor symptoms may respond well to treatment and stop. Some people may have symptoms that worsen slower, thanks to treatment.

When foraminal stenosis becomes severe enough, it usually needs more direct treatments (such as surgery or catheter-based procedures). That’s usually to prevent foraminal stenosis from worsening and/or causing permanent nerve damage or other complications.

Foraminal stenosis happens unpredictably, and even when it happens, it may not cause any symptoms. Because of this, there’s no way to prevent it or reduce the risk of it happening.

If you have foraminal stenosis, you usually won’t need to make any changes or do anything different unless you start to experience symptoms.

If you have back pain, you can try to manage it yourself initially. However, you should see your healthcare provider if you still have it after a few weeks.

If your healthcare provider diagnoses you with foraminal stenosis, they can guide you on what you can do to care for yourself. They can also offer support and information to help you choose possible treatment options.

You should go to the nearest ER if you have sudden severe back pain, especially with an injury, or if you suddenly develop symptoms that could signal an issue with your spinal cord or spinal nerves. Those symptoms include the sudden appearance of:

Foraminal stenosis isn’t usually serious. Most people don’t even know they have it because they don’t have symptoms. It’s only serious if it involves pressure on your spinal nerve that’s severe enough to cause muscle weakness, tingling or numbness.

Foraminal stenosis is a type of spinal stenosis affecting a specific area of your spine. It affects a neural foramen (or more than one), an opening where a spinal nerve exits your spine to branch out into your body. Spinal stenosis refers to narrowing in any part of your spine, not just a neural foramen. It’s also possible to have both at the same time.

The best treatment for foraminal stenosis can vary from person to person. Treatments that help one person might not be as helpful for others. Your healthcare provider is the best person to tell you about possible treatments, especially those likely to help you most and align with your goals and needs.

Most people who have foraminal stenosis don’t know they have it. That’s because most cases don’t cause symptoms. When it does cause symptoms, foraminal stenosis can range from mildly inconvenient to severely disruptive, causing pain and nerve problems that can affect your daily routine and activities. Fortunately, severe cases aren’t common, and there are multiple ways to treat it.

If you suspect you have foraminal stenosis, talking to a healthcare provider is a good idea. Pain and nerve-related issues are often easier to treat early on. That can help you avoid more severe symptoms or complications. And that way, foraminal stenosis is less likely to restrict your life and hold you back from doing things you enjoy.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.