Polydactyly is a birth defect that means your baby was born with extra fingers on their hand or extra toes on their foot. It’s one of the most common birth defects that affect babies’ hands and feet, and it’s easily treatable. If you have a family history of extra fingers or toes, you may want to see a genetic counselor to discuss genetic testing.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/polydactyly)

Polydactyly is the medical term for having extra fingers or toes (digits). You might also see it referred to as hyperdactyly. It’s one of the most common birth defects that affects babies’ hands and feet. Polydactyly (pronounced “paa-lee-dak-tuh-lee”) that causes extra fingers to form on your child’s hand is a form of congenital hand difference.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Using an ultrasound, your healthcare provider may be able to see that your baby has polydactyly before they’re born. But the official diagnosis will happen right after they’re born. Polydactyly can occur on its own, but it may also be part of a genetic disorder. Your baby’s provider will immediately look for signs of other conditions.

You may be a little worried if your baby is born with polydactyly. But having extra digits won’t cause them any symptoms or discomfort. Your baby’s healthcare provider can easily remove the extra finger or toe. If your baby is diagnosed with another genetic condition, they’ll need other types of treatment and care.

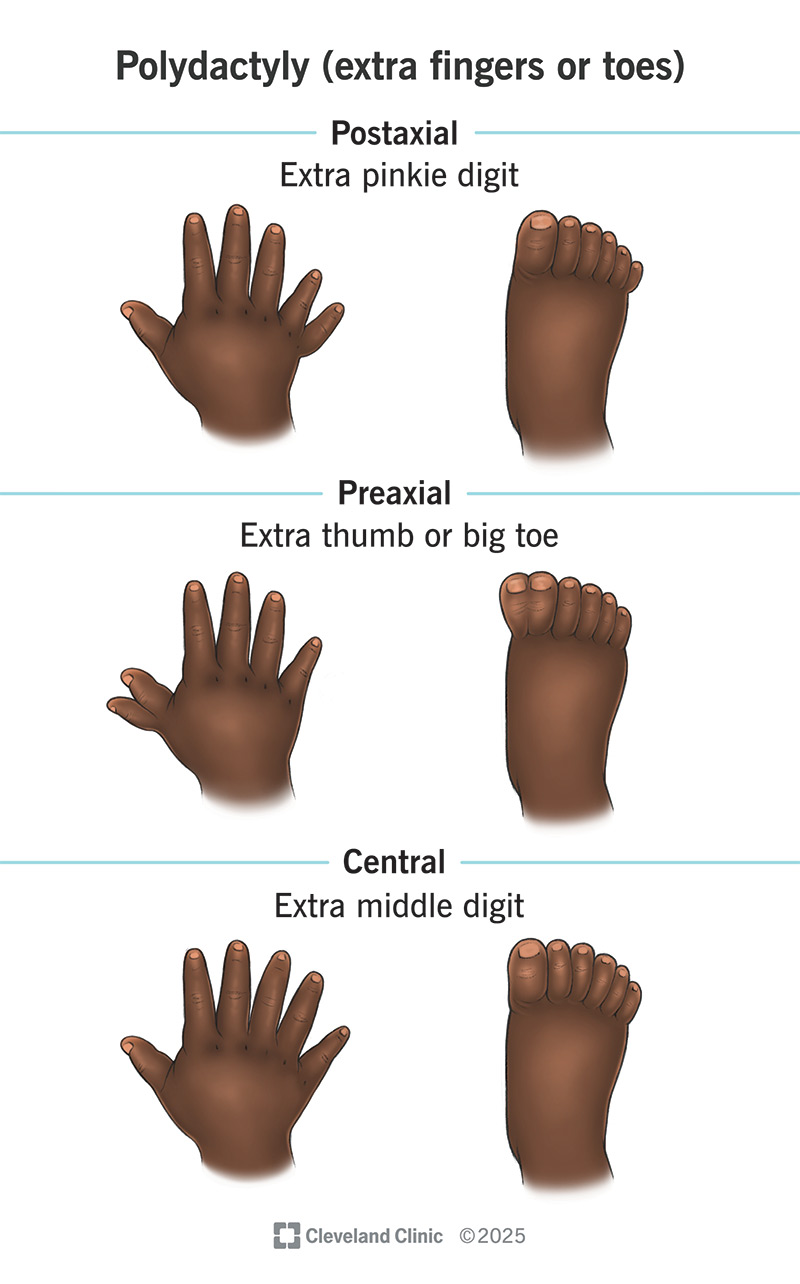

There are three main types of polydactyly. The type depends on which digit has an extra version. The types are:

Advertisement

The only symptom of polydactyly is your child having more than five fingers or toes on their hand or foot. The extra digits will be visible at their birth.

Depending on which type of polydactyly your baby has, their extra fingers or toes might be fully developed and look like the rest of their digits. But the additional digits are usually less developed than typical fingers or toes, and might be attached by only skin or nerves.

A change to your baby’s genes while they’re developing causes polydactyly. Genes are the biological building blocks that you pass down to your children. They contain instructions for the function and growth of every cell in your body.

Anything that interrupts a gene while your baby is developing can cause changes in their body. Sometimes, these changes are things we never notice, and other times, they cause issues like polydactyly and other congenital (present at birth) conditions.

If something disrupts the genes that are responsible for developing your baby’s hands and feet, there’s a chance they might be born with polydactyly. Genetic disorders can interfere with these genes, but so can environmental factors (things that happen to or around someone who’s pregnant).

Genetic disorders that may occur with polydactyly include:

Polydactyly can affect anyone, but the condition occurs in certain babies more than others. Risk factors for developing extra fingers or toes include:

Your healthcare provider may be able to diagnose polydactyly with an ultrasound test before your baby is born. Otherwise, your baby’s provider will be able to diagnose the condition when your baby is born. They’ll identify any extra digits on your child’s hands or feet and will diagnose a type of polydactyly.

Depending on the type of polydactyly, your baby might need a hand X-ray or foot X-ray before receiving treatment.

If you have a biological family history of polydactyly, you may want to speak with a genetic counselor. They can help you decide if genetic testing is right for you. Genetic testing can screen for gene variants, including the variants that cause polydactyly.

Advertisement

If you’re the carrier of a genetic variant, it doesn’t necessarily mean your child will develop a genetic disorder. A genetic counselor can explain your risk and what you can do to protect your health or reduce your risk of passing genetic issues on to your children.

Treatment for polydactyly depends on the type of condition your baby has, but it usually involves removing the extra digit from your child’s hand or foot. There are a few different ways to remove the extra finger or toe. These methods include:

If you notice any changes in your baby’s digits, make a call to their provider. It’s important that your baby sees their provider if they have any pain or if the removal site has any of the following symptoms:

Advertisement

Don’t worry if your baby has polydactyly. You can expect them to make a full recovery after they have the extra digit removed. The removal process will have no impact on their future growth or development.

If your child has another birth defect or genetic condition, they might need other types of treatment or care. Talk to their healthcare provider about what to expect in the future.

It might be surprising to see an extra finger or toe after your baby is born. But don’t be too alarmed. Polydactyly is a treatable condition that has no long-term impacts on your baby’s growth and development. All methods of removal have quick recovery times and won’t impact your baby’s ability to use their hand or foot in the future. If you have any concerns about this or other genetic conditions, talk to your healthcare provider.

Advertisement

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

As your child grows, you need healthcare providers by your side to guide you through each step. Cleveland Clinic Children’s is there with care you can trust.