Esotropia, a type of eye misalignment, happens when one or both of your eyes turn inward toward your nose. Common treatments include glasses or contact lenses, surgery or injections of botulinum toxin.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/esotropia)

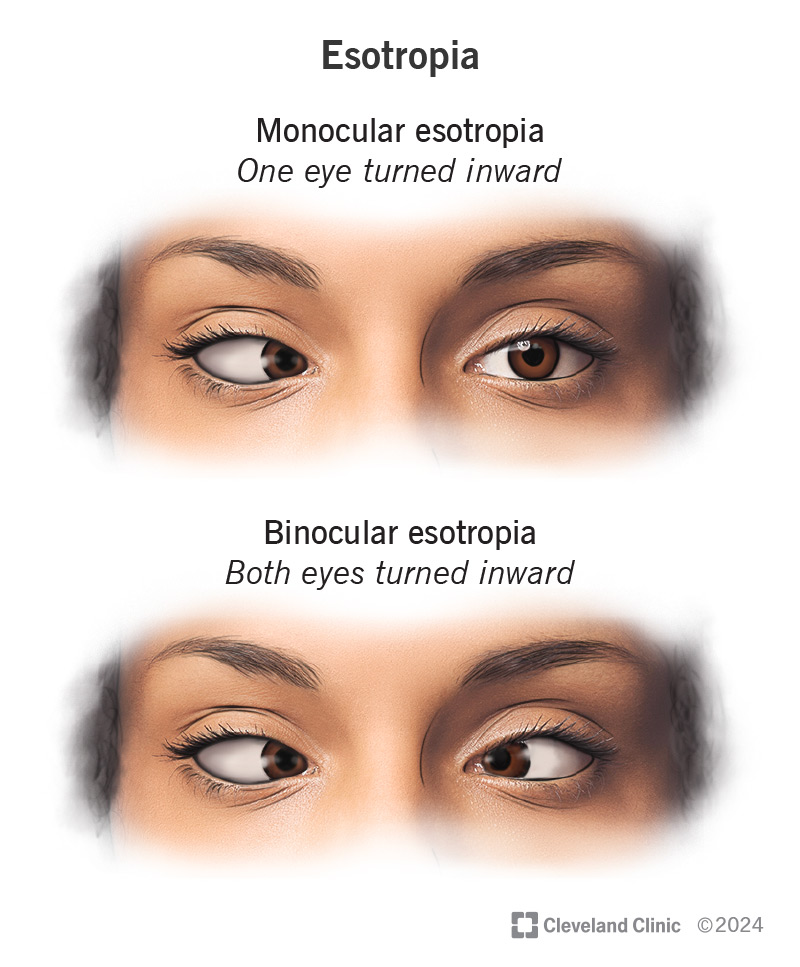

Esotropia is an eye condition in which one or both of your eyes turn inward. It’s a type of strabismus, which means that your eyes don’t line up or align correctly. Some people refer to esotropia as being “cross-eyed.” Esotropia can be monocular (involves one eye) or binocular (involves both eyes).

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

The muscles and nerves that control your eyes usually allow both of your eyes to work together. In esotropia, this control isn’t as coordinated as it should be. Esotropia is the opposite of exotropia, the turning outward of your eyes.

Although esotropia can happen at any age, it commonly occurs in babies and children. It can affect not only your child’s vision but also their social and emotional development. Many children experience reduced self-esteem due to the appearance of the condition. That’s why it’s important to seek diagnosis and treatment as soon as you notice symptoms.

There are many different kinds of esotropia, including:

Advertisement

The main symptom of esotropia is that one or both of your eyes turn inward toward your nose. You may not be able to see it yourself if you have it. Other symptoms may include:

Esotropia is caused by a lack of coordination of your eye muscles. Usually, your eye muscles work together, as a binocular system (“seeing with two eyes”). You can tell how close you are to something. It’s important for eyes to work together while you’re riding a bicycle, driving a car or reading.

Young children with esotropia are typically farsighted, meaning they can see things that are farther away more clearly than things that are closer. Sometimes, esotropia is a sign that you need glasses to correct farsightedness.

Esotropia is sometimes genetic. You may have other biological family members with misaligned eyes.

Esotropia can be a sign of other conditions, including:

Esotropia has many potential risk factors, including:

Esotropia makes it hard for your eyes to work together, which can lead to:

In addition, people are likely to experience a loss of self-confidence due to cosmetic concerns, which can lead to social anxiety and performance issues in school and other activities.

Your healthcare provider may refer you to an ophthalmologist or optometrist. The provider will ask about your family and medical history and perform an eye examination. They may perform the following tests:

Some cases of esotropia may get better on their own. For those that don’t, your eye care specialist may suggest one of these treatments or a combination of treatments, including:

Advertisement

If you have esotropia as a symptom of some other condition, your healthcare provider will treat that condition. Esotropia usually improves when you manage whatever’s causing it.

If you have treatment for esotropia, like getting glasses or contacts or having surgery, your prognosis (outlook) is good. It’s important to follow your treatment plan carefully and see your provider for regular follow-up appointments.

You can’t prevent esotropia entirely, but you can help your child manage it by taking them for regular eye exams as soon as you notice any changes in their eyes or vision.

If your child’s eyes are bothering them at any point — you notice them squinting a lot or moving objects around to try to focus better — call their healthcare provider. This is also true for you.

If your eyes, or your child’s eyes, change suddenly and look different, call your provider, especially if the changes happen after some type of injury. After an injury, get help right away.

Questions you may want to ask your child’s provider include:

Advertisement

Esotropia is a common eye condition that can affect your vision, which makes work, sports and daily activities difficult. In addition, it can impact your self-image and make social interactions harder than they need to be. If you or your child has esotropia, it’s important to get a timely diagnosis. The sooner you begin treatment, the sooner it can correct your eye alignment.

Advertisement

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Getting an annual eye exam at Cleveland Clinic can help you catch vision problems early and keep your eyes healthy for years to come.