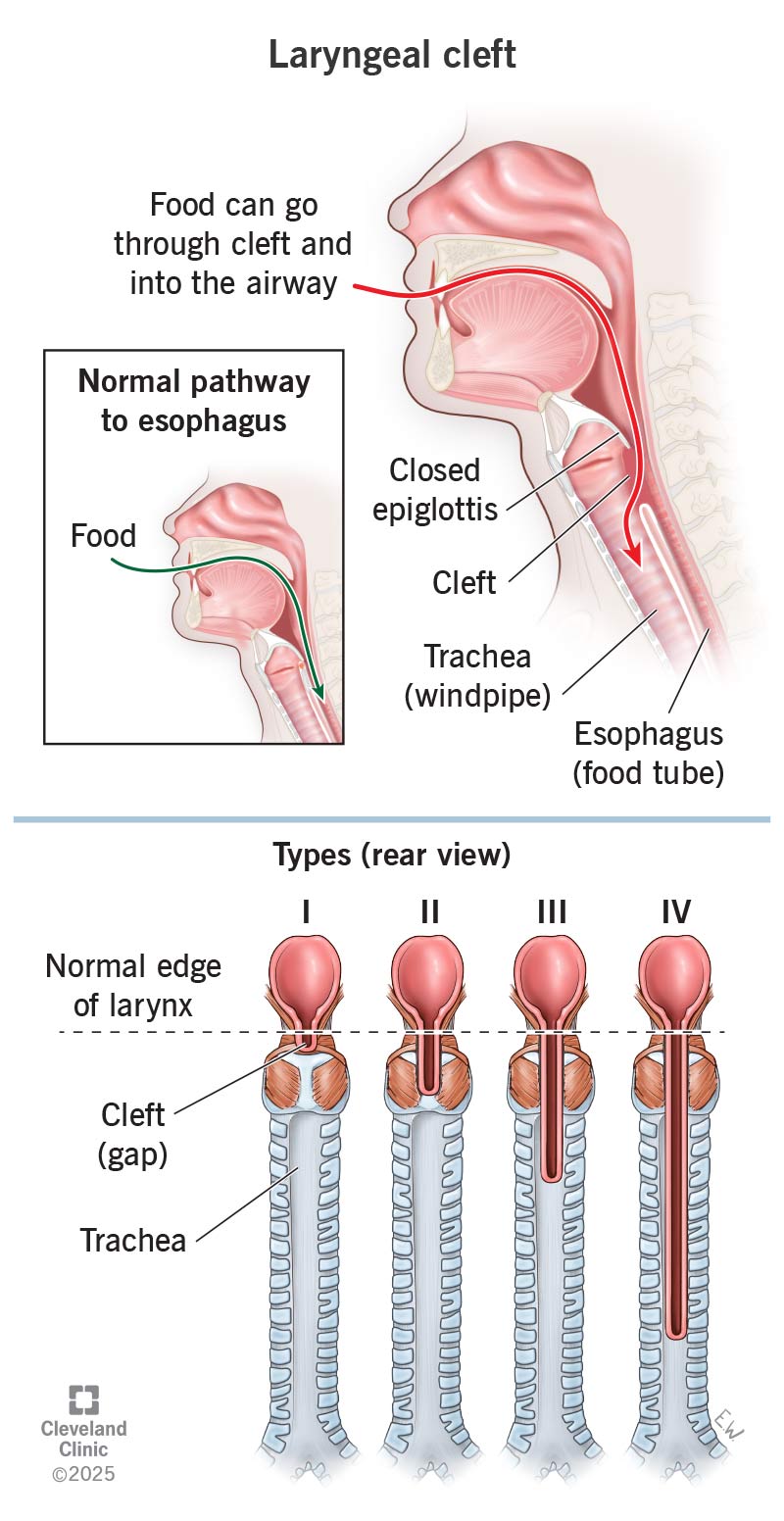

Laryngeal cleft is an abnormal opening in the tissues between your child’s larynx (voice box) and esophagus (food pipe). Instead of going in their esophagus, food and liquids can enter their trachea (windpipe) and lungs. This can cause choking, wheezing, coughing and breathing problems. Your child may need surgery to close the opening.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/Images/org/health/articles/laryngeal-cleft)

Babies born with a laryngeal cleft have a gap in the tissues between their larynx (voice box) and esophagus (food tube). The abnormal gap creates an opening between their larynx, which sits atop their trachea (windpipe), and esophagus. This allows food and liquids to enter the opening and travel into your baby’s lungs instead of their stomach.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Laryngeal cleft is a rare birth defect (congenital condition). It’s only present in 1 in 10,000 to 20,000 live births. It’s slightly more common in male babies.

If your child is born with this condition, it’s important that they get diagnosed as soon as possible. Food and liquids traveling down the wrong pipe can cause all sorts of issues. But how serious a laryngeal cleft is depends on the size and location of the gap.

There are four main types of laryngeal cleft:

A laryngeal cleft can make it harder for your child to eat and breathe. Symptoms include:

Advertisement

Researchers don’t know the exact cause of a laryngeal cleft. But it likely develops during the first few months of fetal development. It can happen on its own or as part of an underlying syndrome like:

More than half of children with laryngeal clefts have other congenital conditions, such as:

Milder forms of laryngeal cleft, like types I and II, may not get diagnosed for years. Healthcare providers usually diagnose types III and IV within the first few days of a baby’s life because of how severe their symptoms are.

If your child has laryngeal cleft symptoms, an otolaryngologist (ear, nose and throat doctor) may perform an endoscopic evaluation. The most common method for laryngeal cleft diagnosis is a microlaryngoscopy and bronchoscopy. Your child will receive anesthesia that puts them to sleep for the procedure. The otolaryngologist will then insert a camera into your child’s windpipe. They’ll use an instrument to feel for a cleft.

Your child may need to meet with a speech-language pathologist (SLP). This specialist will check how their condition impacts their ability to speak and swallow.

Laryngeal cleft typically requires surgery called laryngeal cleft repair. This is especially the case for types II, III and IV. Sometimes, children compensate for type I as they grow. Children with type I may only need medicines to prevent reflux and food going down the wrong tube (aspiration).

The timing and type of surgery vary depending on the specific laryngeal cleft. Surgeons may repair them using:

If your child needs surgery, their healthcare provider will give them anesthesia to put them to sleep beforehand. They won’t feel any pain.

Risks involved with laryngeal cleft surgery include:

Advertisement

The chances of a complication depend on lots of factors, including the type of procedure and cleft, and your child’s overall health. Your child’s healthcare provider will discuss this with you beforehand.

After surgery, your child will stay in the hospital for at least a day or two. Because surgery involves sutures to close the cleft, it takes a few weeks or months to heal completely.

With early diagnosis and treatment, the outcome for children with a laryngeal cleft is good. According to a recent study, 9 out of 10 children who receive laryngeal cleft repair experience improvements within six weeks. But much depends on how advanced the cleft is. Those with type IV have a higher chance of needing more than one surgery and longer hospitalization.

Your child’s healthcare provider will talk to you about your child’s prognosis and follow-up care.

For most children, having a laryngeal cleft doesn’t impact how long they’ll live. But some babies who have advanced type IV laryngeal cleft and other severe congenital conditions may not survive. But fatalities related to laryngeal cleft — even when it’s advanced — are extremely rare.

With proper treatment and follow-up care, a laryngeal cleft doesn’t have to shorten your child’s life expectancy or reduce their quality of life.

Advertisement

After surgery, your child’s provider may recommend follow-up appointments every six months up to a year. How many visits your child needs within that time depends on how they’re doing.

During these appointments, your child’s provider may do imaging tests and ask about their symptoms. Come prepared to speak for your child. Discuss any changes you’ve noticed related to their symptoms and overall health.

Questions to ask your child’s healthcare provider include:

If your baby is born with a laryngeal cleft, you’ll meet with various specialists who will ensure your child gets the care they need. Sometimes, the cleft fills in on its own. In that case, your child may only need close monitoring. With more severe clefts, your child may need surgery. The important thing to remember is that there are treatments that can help. In the meantime, ask your child’s healthcare provider about ways you can help your child cope with this diagnosis.

Advertisement

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic's health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability, and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic's health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability, and up-to-date clinical standards.

If you have conditions affecting your ears, nose and throat, you want experts you can trust. Cleveland Clinic’s otolaryngology specialists can help.