Diphtheria is a serious infectious disease that often causes breathing and swallowing problems. It can cause sores on your skin, as well. Due to widespread vaccine use and improved living conditions, diphtheria is very rare in the United States. But diphtheria outbreaks exist in other parts of the world.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/diptheria)

Diphtheria is a contagious bacterial infection that typically affects your throat and nose. The bacterium releases a toxin that causes a buildup of grey tissue in your throat. This leads to problems with swallowing and breathing. It can affect other parts of your body, as well.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Diphtheria is treatable, but it can be life-threatening.

Diphtheria is very rare in the U.S. because of widespread use of the diphtheria (Tdap) vaccine and cleaner living conditions. The diphtheria epidemic peaked in 1921 in the U.S. with 206,000 cases.

In other countries with limited or no vaccines, the disease still exists. Diphtheria is endemic (an outbreak that’s limited to a certain region) in Southeast Asia, India and other parts of the world.

There are two main types of diphtheria:

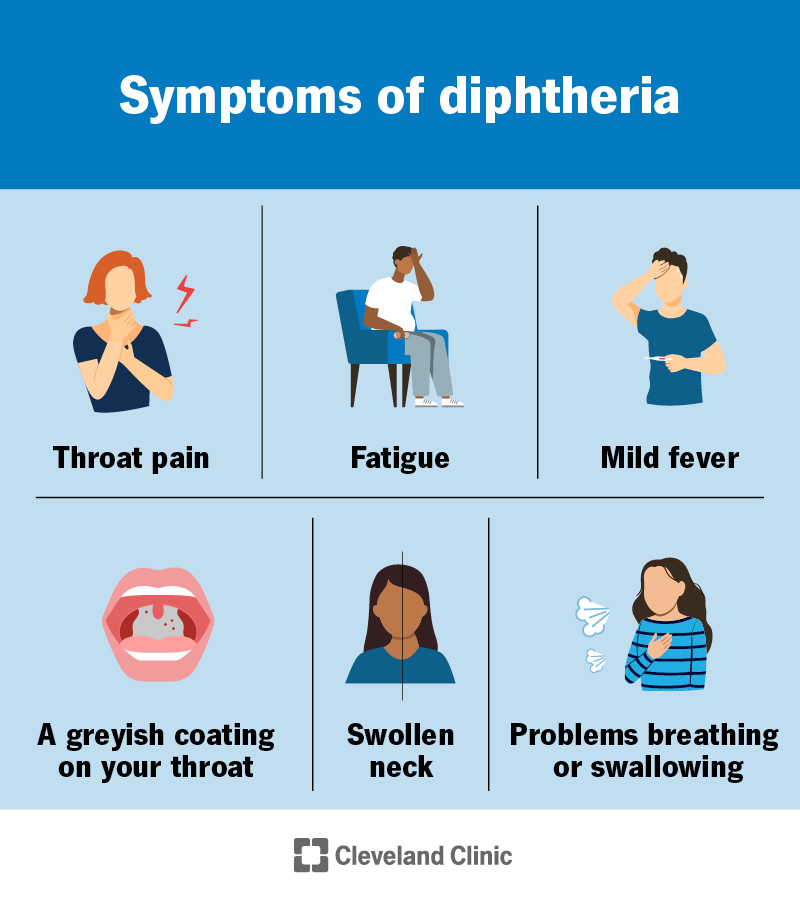

Common diphtheria symptoms include:

Symptoms of skin diphtheria can include:

Signs of diphtheria usually show up around two to five days after exposure. But this can range from one to 10 days. Some people don’t have symptoms or have mild symptoms. But they can still spread the bacteria.

Advertisement

See a healthcare provider immediately if you have these symptoms or have been near someone with diphtheria.

A bacterium called Corynebacterium diphtheriae causes diphtheria. The bacteria stick to the lining of your airways. They then make a toxin that damages your respiratory tissue cells.

Within a few days, a bulky, grey coating forms. It can cover tissues in your voice box, throat, nose and tonsils. Breathing and swallowing may become difficult. The toxins can damage other parts of your body, too.

If you don’t have the diphtheria vaccine and come in close contact with an infected person, you can develop the infection. You can get it through:

Without vaccination, you can get diphtheria more than once.

A lack of the diphtheria vaccine and/or not having a booster shot are the main risk factors for having severe diphtheria symptoms. Other risk factors for severe disease include:

Risk factors for exposure include:

Diphtheria can lead to complications, like:

These complications can result in death.

Healthcare providers diagnose diphtheria based on your symptoms and the results of a lab test. They’ll use a swab to take a sample from the back of your throat (or a sore). A lab then tests the sample for the bacterium that causes diphtheria.

Diphtheria treatment begins immediately — sometimes even before the lab test results come back. You may get diphtheria antitoxin to stop damage to your organs. You’ll also need antibiotics to fight the infection.

During treatment, you’ll stay in a hospital room by yourself (in isolation) to prevent others from getting sick. In most cases, you’re no longer contagious about 48 hours after starting antibiotics. But it takes about two to three weeks for treatment to be effective. Skin ulcers can take months to heal.

When treatment ends, your provider will run more tests to make sure the bacteria are gone.

See your healthcare provider if you:

Advertisement

Treatment for diphtheria can be effective. But, even with treatment, it can still cause death.

One study estimates that the fatality rate of diphtheria is around 30% for people without vaccination and treatment. Children under 5 years old are at a higher risk of dying without vaccination and treatment.

Yes. Vaccination is highly effective at preventing symptomatic diphtheria. The prevention rate is over 87% with three doses of the vaccine.

The U.S. uses three types of combination vaccines that include protection against diphtheria. They include DTaP, Tdap and Td. They protect you against multiple infections at once, like pertussis (whooping cough) and tetanus, too.

Talk to your healthcare provider about diphtheria immunization schedules. They can vary based on your age. Immunity can wear off over time, so you’ll need a booster about every 10 years if you’re an adult.

Many people have questions about vaccines. Healthcare providers welcome those conversations. They want you to feel confident in the decision you make.

Diphtheria is a risk you can avoid with the right medical care. Talk to your healthcare provider about vaccines, especially if you’re traveling to an area where diphtheria is more common. If you have any symptoms of diphtheria or possible exposure, go to the nearest emergency room. Diphtheria can be dangerous without quick treatment.

Advertisement

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Have a virus, fungus or bacteria? Some of these “bugs” won’t go away on their own. Cleveland Clinic’s infectious disease experts are here to help.