Polymyositis is a rare disease that makes your immune system attack your muscles. It causes inflammation and weakness in muscles close to the center of your body, which can lead to severe, life-threatening complications. Visit a healthcare provider if you notice new muscle weakness, pain or fatigue.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/polymyositis-infographic)

Polymyositis is a rare autoimmune disease that makes your immune system attack your muscles.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

It’s a type of myositis. Myositis causes chronic inflammation in your muscles — swelling that comes and goes over a long time. Eventually, this inflammation makes your muscles feel weak.

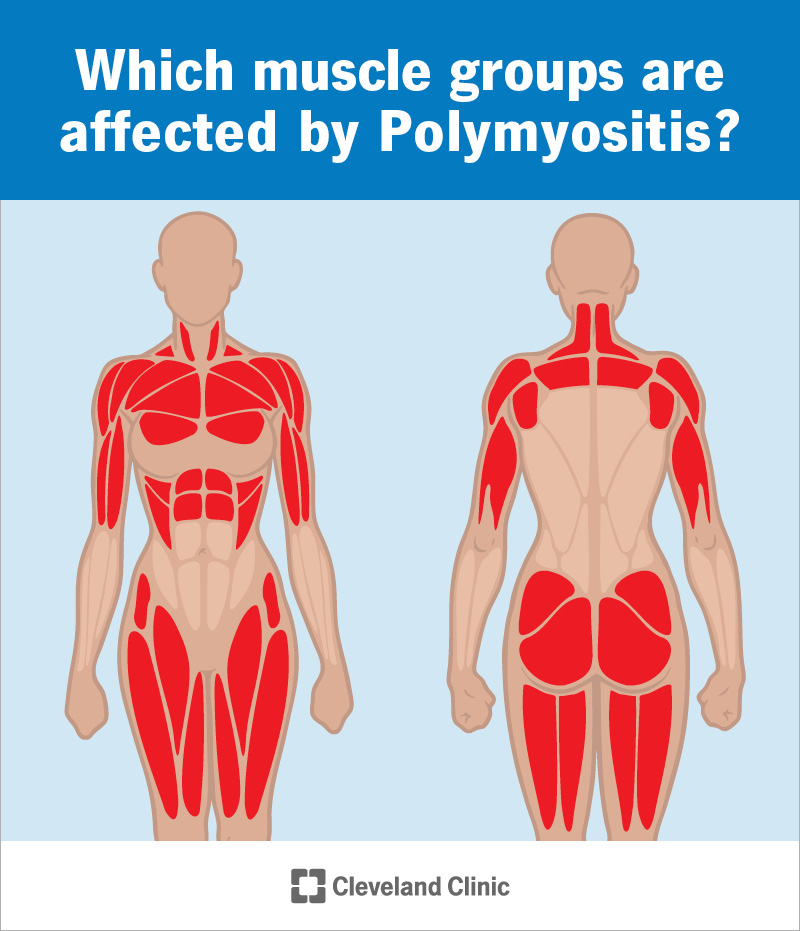

If you have polymyositis, you may have inflammation in multiple muscles at the same time. It usually affects the muscles on or near the center of your body, including in your:

Experts aren’t certain what causes polymyositis, and there’s no cure for it. A healthcare provider will treat the symptoms you’re experiencing and suggest ways to manage how much they affect your daily routine.

Polymyositis is rare. Experts estimate that it affects fewer than 25 out of every 100,000 people every year.

The most common polymyositis symptoms include:

You might have trouble moving or doing activities you usually can, including:

Advertisement

Some polymyositis symptoms can cause life-threatening complications. Talk to a healthcare provider about which symptoms to look out for. Go to the emergency room or call 911 (or your local emergency services number) if you feel like you can’t breathe or swallow.

Polymyositis is an autoimmune disease, but experts aren’t sure what causes it. Autoimmune diseases happen when your immune system accidentally attacks your body instead of protecting it.

Polymyositis can start on its own with no cause (idiopathically). Sometimes, other health conditions or reactions to medications trigger it.

You’re more likely to develop polymyositis if you have other autoimmune diseases, including:

Some viral infections can trigger polymyositis, including:

Anyone can develop polymyositis, but some groups of people are more likely to, including:

A healthcare provider will diagnose polymyositis with a physical exam and some tests. They’ll ask about your symptoms and examine the muscles that are feeling weak or experiencing symptoms. Your provider will ask you how it feels when you do certain movements or motions.

Your provider will use a few tests to diagnose polymyositis. Some of these tests will rule out other conditions that can cause similar symptoms. Your provider might use:

There’s no cure for polymyositis. Your provider will suggest treatments to manage the inflammation. Treatments can’t make the polymyositis go away, but it can reduce how much symptoms affect your day-to-day life. Many people reach a period of remission (when there’s no inflammation in your affected muscles).

The most common treatments for polymyositis include:

Advertisement

People usually live with polymyositis for the rest of their lives. There’s no cure for it, but most people find a combination of treatments that helps them put polymyositis into remission.

Some cases of polymyositis cause life-threatening complications. It can be fatal if polymyositis severely affects or damages the muscles in your throat and chest that help you breathe and swallow.

Because experts aren’t sure what causes it, there’s no way to prevent it. We can’t predict who will develop it or when episodes of symptoms will happen or come back.

Visit a healthcare provider right away if you experience new muscle weakness, pain or other symptoms — especially if they don’t get better in a few days.

Talk to your provider if your symptoms get worse or spread. Tell your provider if you feel like your treatments aren’t working as well as they used to, or if it seems like you’re having more (or more severe) polymyositis episodes.

Go to the emergency room or call 911 (or your local emergency services number) if you experience any of the following symptoms:

Questions you may want to ask your provider include:

Advertisement

Some studies have found that polymyositis (and other types of myositis) might have a genetic component. This means that biological parents might pass specific genetic mutations to their children that make them more likely to develop a condition.

However, experts haven’t been able to identify specific genetic mutations that cause polymyositis, and they can’t prove that there’s an increased risk your biological children will develop polymyositis if you have it.

Talk to your healthcare provider about genetic counseling if you’re worried about the risk of passing certain conditions to your biological children.

Polymyositis won’t usually affect your life expectancy (how long you’ll live). But it can cause fatal complications, especially if it causes severe weakness in your neck and throat muscles. Talk to your healthcare provider if you’re noticing that it’s getting harder to breathe or swallow. They’ll help you adjust your treatments to manage these symptoms before they can cause dangerous complications.

Advertisement

Polymyositis causes inflammation and weakness in your muscles, usually along the center of your body. You’ll probably have to manage symptoms in periods of episodes that come and go for the rest of your life. There’s no cure for polymyositis, but your healthcare provider will help you find a treatment plan that reduces how much it affects your day-to-day life. Many people are able to put polymyositis into remission and reduce how often they experience symptoms.

Talk to your provider about your risk of severe complications, especially in the muscles that control your swallowing and breathing. They’ll help you understand warning signs to watch out for.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic's health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability, and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic's health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability, and up-to-date clinical standards.

Are you recovering from an injury, surgery or illness? Cleveland Clinic’s physical therapy team will help you get back to what you love to do.