Trained as an engineer and seasoned by decades of leading and advising global brands, Jeremy Schwartz grounds every major decision in facts and data. He calls this approach “finding the truth of the problem.”

Relying on vivid dreams or startling premonitions? That was never part of how the 62‑year‑old executive ran his businesses or his long‑standing management consulting firm.

But in the early hours of Sunday, August 31, 2025, Jeremy woke abruptly at 3 a.m. with a disturbing, exceptionally detailed dream still clear in his mind. In it, he died suddenly of a heart attack while climbing Ama Dablam—Nepal’s towering peak often called the “Matterhorn of the Himalayas.” The timing made it even more unsettling because he was scheduled to attempt that very climb during a month‑long trip to Nepal in October.

“I am not a tarot card reader or a spiritualist, and I’m not religious,” says Jeremy, who lives in Surrey, England, and travels the world for both business and for cycling and mountaineering pursuits. “I’ve never had anything like a premonition before. But this dream was so strong and so clear it left me with an overwhelming sense of importance and urgency.”

Jeremy quickly arranged an online consultation with a cardiologist. Two days after his premonition he had an in‑person appointment. A series of heart scans and additional tests led to a startling diagnosis: he had an aortic aneurysm—a bulge in the wall of the heart’s main artery that could rupture without warning.

Jeremy on Alpamayo in Peru, in August 2025, embracing the active, adventurous life he loves. (Courtesy: Jeremy Schwartz)

The cardiologist urged him to cancel his upcoming Nepal trip, avoid all strenuous activity, and prepare for surgery before year’s end. A climb up Ama Dablam, he warned, would almost certainly have been fatal.

“It was a complete shock,” Jeremy recalls. Earlier in 2025 he had completed both a 1,000‑mile cycling trip across the length of Italy and a solo, 120‑mile circumnavigation of a mountain range in Albania. “But I think my subconscious helped make sure I became aware of something that might otherwise have remained hidden.”

Mr Cesare Quarto, MD, PhD, a consultant cardiac surgeon at Cleveland Clinic London who would perform Jeremy’s surgery a few weeks later, says he is not surprised a premonition prompted Jeremy to seek medical care.

“I strongly believe some patients have an internal alarm bell that starts ringing. Some are able to hear it, and some aren’t,” says Mr Quarto, a specialist who frequently undertakes complex cardiac procedures. “It is not the first time I have heard a similar story.”

Looking back, Jeremy believes several factors may have contributed to the intuition he felt about his upcoming climbing expedition. About a year earlier, while on a business trip in South Africa, he recorded a higher‑than‑normal blood pressure reading. With no other symptoms, he didn’t think much of it at the time and chose not to pursue further testing.

Additionally, a friend from his local cycling club had died suddenly of a heart attack while riding. Jeremy’s father, too, had passed away unexpectedly at roughly the same age as Jeremy. And later, he learned on the very day he was scheduled to climb Ama Dablam, another climber on the mountain collapsed and died from a heart attack.

“One of the challenges for men is we often delay taking important medical action,” Jeremy explains. He is currently organising a heart and prostate cancer screening event for men in his community outside London. “A lot of these conditions are preventable or treatable if you catch them early. That’s why I went into my surgery with all guns blazing. Let’s get this thing done!”

The six‑hour surgery was completed without complications, due in part to a specialised technique that removes the damaged portion of the aorta without replacing the healthy aortic valve or aortic root. This reimplantation approach, known as the David procedure, can also speed recovery by reducing the risk of postoperative complications.

Jeremy walking at Cleveland Clinic London with the help of his care team after undergoing heart surgery. (Courtesy: Jeremy Schwartz)

Soon after Jeremy woke from surgery, a Cleveland Clinic nurse encouraged him to get out of bed and sit in a nearby chair. Within a day, he began taking a few cautious steps, gradually progressing to longer walks through the hospital corridors.

“I had amazing nurses whose care, kindness, and attention were fantastic,” Jeremy says. “Paired with the expertise of the doctors—especially Mr Quarto, who performs countless heart surgeries yet still rehearses each one with incredible dedication—I felt completely confident and deeply grateful for the care I received.”

After just eight days, Jeremy was discharged and continued his recovery at home in the countryside. As he regained strength, and as the weather turned colder, he bundled up and walked up and down an 80‑metre paved path outside his house.

“Each day I walked, first just one length of the path, then two, then four. Eventually, I worked up to 60 trips back and forth in an hour,” he says. “That’s when I realised I could probably venture farther beyond the house.”

Recently, Jeremy has begun more rigorous cardiac rehabilitation, guided by a physiotherapist over virtual appointments. His sessions now include increasingly challenging intervals on a stationary bike, and he will soon resume weight training.

He has also returned to work, traveling to Japan, and soon, Florida to attend conferences and deliver presentations. He hopes to eventually return to mountaineering. His goal is to join his son in August 2026 for a long‑planned trip to Peru to climb a mountain in the Andes.

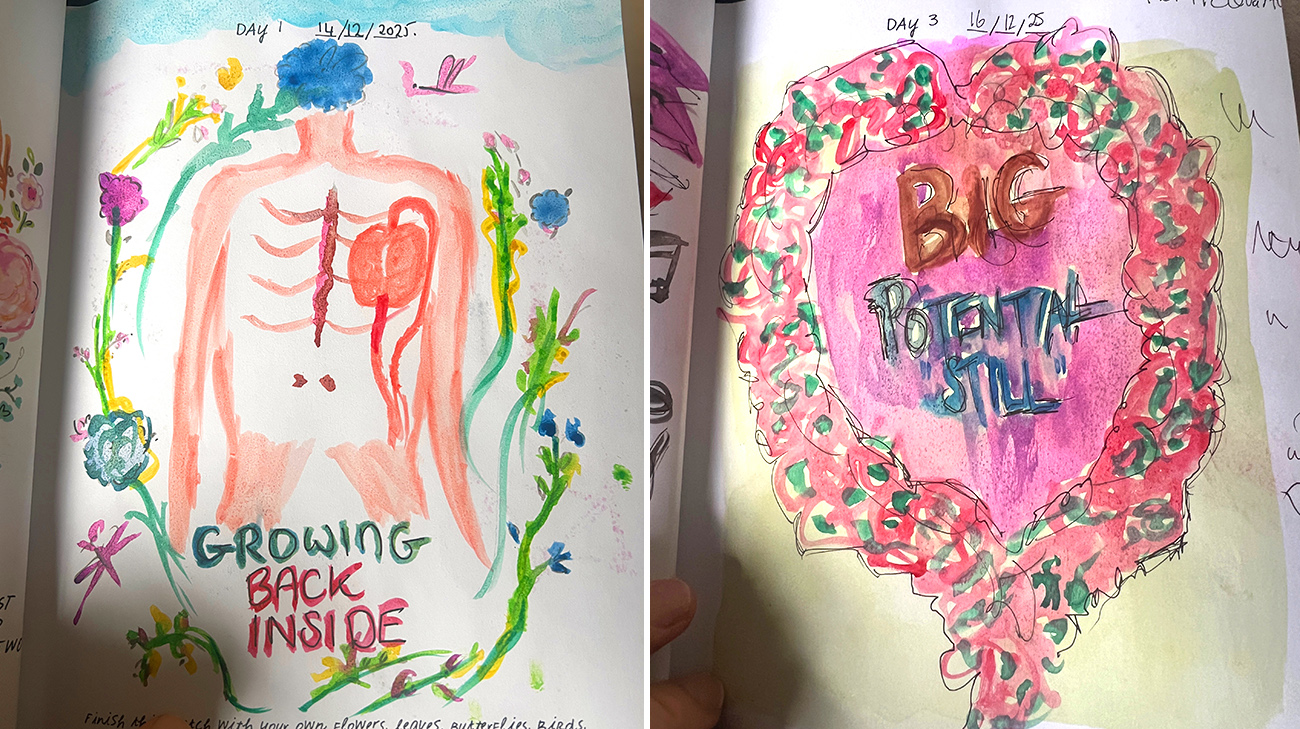

Paintings Jeremy created to express that, even after heart surgery, he can still live life to the fullest. (Courtesy: Jeremy Schwartz)

“Whether I go all the way to the top, I haven’t decided yet. But Mr Quarto and my physiotherapist are both convinced that after rehab, I should be as fit—if not fitter—than I was before.”

Mr Quarto notes that, after heart surgery and proper rehabilitation, most patients can return to a full, active life. “Isn’t that why we do the operation?” he says. “Patients often ask, ‘Will I be able to run a marathon?’ And I ask them, ‘Have you ever run a marathon before?’ If you could do it before, you can do it afterwards.”

Jeremy is passionate about encouraging others, especially men, to pay attention to their health and not ignore warning signs. “If something feels wrong, it’s not clever or manly to pretend it isn’t,” he says. “Don’t wait, don’t rationalise, don’t tough it out. Get it checked out. It’s how you get to keep living the life you love.”

Related Institutes: Heart, Vascular & Thoracic Institute (Miller Family)