Caleb Root is passionate about sports and has his sights set on running track and field in college. But until recently, Caleb felt like he couldn’t take a deep breath even as an active teenager.

“I felt like I should be in shape but was just so out of breath when participating in sports. It was almost like something was stopping me from being able to breathe normally,” says Caleb.

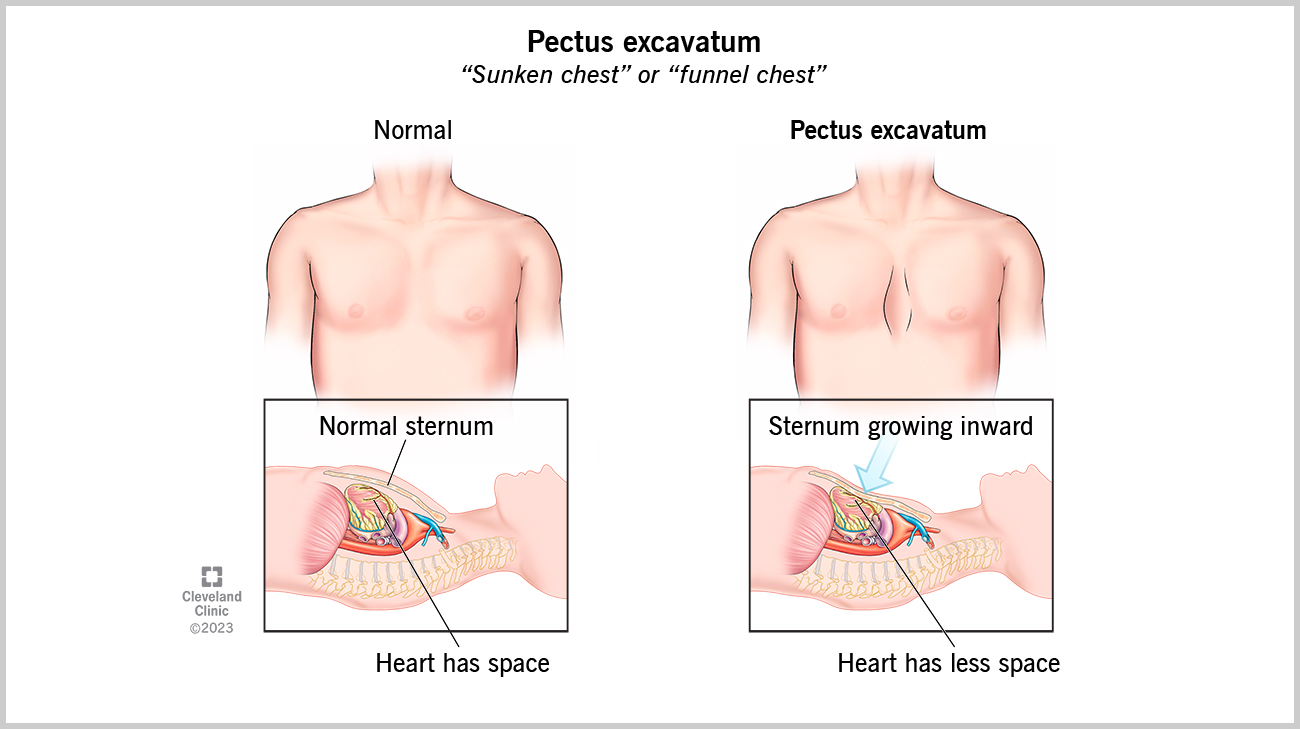

Caleb was diagnosed with a congenital condition called pectus excavatum. With pectus excavatum, your breastbone (sternum) grows inward, making less space in your chest. (Courtesy: Cleveland Clinic)

His shortness of breath was due to a congenital condition called pectus excavatum, which refers to an inward growth of the sternum that creates a noticeable and sometimes severe indentation of the chest wall. It was around the time Caleb became a teenager when he and his family started noticing something was different about his chest.

“I became a little self-conscious about it. When I went to the pool and took my shirt off, I knew people would see me kind of differently,” says Caleb.

Caleb’s mom Bridgett says they first sought care locally where they live in Toledo, Ohio, but based on their doctor’s recommendation, ultimately came to see John DiFiore, MD, Director of the Center of Excellence for Minimally Invasive Repair of Pectus Excavatum at Cleveland Clinic Children’s for a second opinion. Here, they learned how the condition was physically impacting Caleb.

CT imaging shows Caleb’s pectus excavatum before undergoing surgery. (Courtesy: Cleveland Clinic)

“The most common symptom for pectus excavatum is shortness of breath with exertion. If the sternum is pushed inward, there's less room for the lungs to expand. Because the heart also sits right behind the sternum, if there's a significant indentation of the sternum, the back of the sternum will compress the heart, leading to an inability of the heart to pump enough blood to the lungs when the demand is increased by exercise,” says Dr. DiFiore.

After additional testing showed how his heart and lung function were significantly impaired, Caleb and his family decided to look at surgical options with his care team. Dr. DiFiore explains there is a minimally invasive surgical repair to fix pectus excavatum called the Nuss procedure, which involves using one or more metal bars to push a person’s breastbone forward.

“We put those curved metal bars internally behind the sternum to lift it into the proper plane of the chest wall,” says Dr. DiFiore. “The bars essentially work the same way braces do for your teeth in that they apply a continuous mechanical force on the sternum and ribs, so they will reshape and remodel over the three-year time period the bars are left inside the chest.”

Chest X-ray shows the metal bars used to push Caleb’s breastbone forward. (Courtesy: Cleveland Clinic)

According to Dr. DiFiore, patients used to be in the hospital for about one week after this type of surgery. But due to advancements in pain management, Caleb, who was 14 years old when he underwent the procedure, was able to go home after one night in the hospital. Dr. DiFiore says his team at Cleveland Clinic was among the first in the country to use a technique called intercostal nerve cryoablation.

“There’s a nerve that runs along the bottom of each rib which supplies the pain sensation to the chest wall. With intercostal nerve cryoablation, we freeze that nerve to temporarily disrupt its ability to transmit pain signals,” says Dr. DiFiore.

Bridgett adds, “Having the ability to freeze the nerve endings and not having Caleb spend a week in the hospital was really huge for us.”

Caleb’s passion for track and field grew following surgery to address his pectus excavatum. (Courtesy: Shakhan Kelly Photography)

After surgery, there was a six-month waiting period until Caleb could participate in contact sports. However, after three months, he was cleared for non-contact sports. That’s when he found his passion for track and field. After three years, the bars were removed from his chest, and he noticed a significant difference in his performance.

“During my first track season without the bars, I felt like I was as fit as everyone else and could breathe. When I take a deep breath now, it feels like I can fill my lungs,” says Caleb.

During the 2024 Ohio High School Athletic Association track and field championships, Caleb finished second in the 300-meter hurdles and sixth in the 100-meter hurdles. “This was my first time running at the state meet individually, and the time I ran was eye opening to me, where now I feel I can really run Division I track in college. It was a great moment for me,” says Caleb, who no longer has any limitations when it comes to his activities.

Caleb’s chest before and after surgery for pectus excavatum. (Courtesy: Cleveland Clinic) Caleb at the 2024 Ohio High School Athletic Association track and field championships. (Courtesy: Bridgett Root)

Looking at the before and after photos of his chest, the 17 year old recalls one pre-surgery photo where his heart was pressed up against his chest. Following the procedure, Caleb’s heart and lungs are no longer being compressed, and he’s happy with the appearance of his chest.

“I’d say my confidence has improved. I do have some small scars on my chest now, but I’ve grown to embrace them. It's something unique about me I think is kind of a cool story now,” says Caleb.

Related Institutes: Cleveland Clinic Children's