Neil Freeman’s wife, Koreen, was the first to notice something unusual was happening to her husband. They were at dinner, in their Watertown, New York, home, when she saw the left side of his face was sagging alarmingly. At about the same time, Neil, age 59, began to lose all feeling on the entire left side of his body, and nearly slid, uncontrollably, out of his chair.

He knew instantly he was having a stroke, and as they waited for an ambulance to arrive, Neil began fearing the worst as the numbness, droopiness and related symptoms persisted. “I thought I was going to be an invalid, spoon fed and in a wheelchair the rest of my life,” recalls Neil, a financial planner and former wrestling coach. “I’ve always been active, and now I’m not going to have the use of half of my body.”

While the symptoms eventually went away after about 90 minutes, and Neil’s health returned, he had additional mini-strokes over the next few days. Already scheduled to visit Cleveland Clinic for a second opinion related to persistent heart valve issues, Neil was transferred from a hospital in New York, to Cleveland Clinic earlier than planned, after his local doctors made the assumption his heart and stroke issues were related.

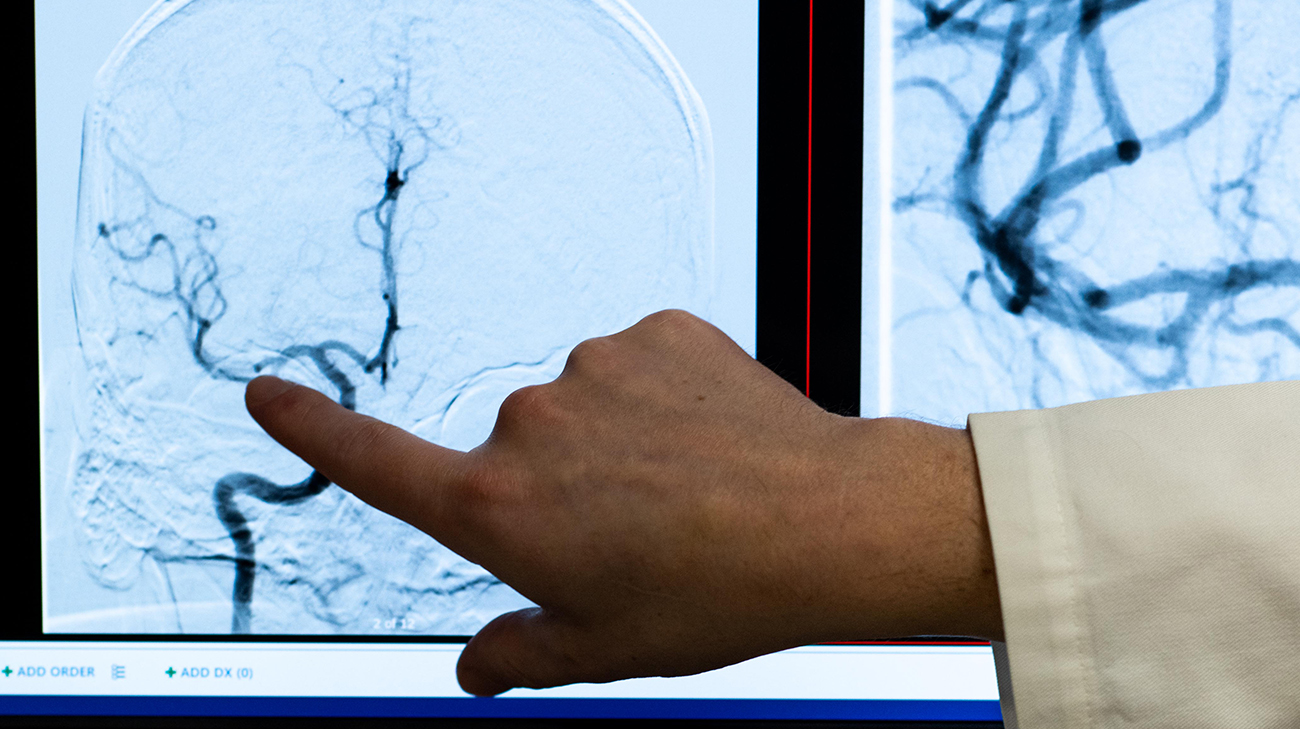

One of Neil's neurologist's Blake Buletko, MD, reviewing Neil's brain scans at Cleveland Clinic. (Courtesy: Cleveland Clinic)

They were right. A multidisciplinary team of Cleveland Clinic neurologists, cardiologists, hematologists and other specialists determined a prosthetic heart valve that had been implanted in Neil a few years earlier had most likely calcified. Chunks of calcium broke off from the valve and traveled through his bloodstream.

Some of the debris likely settled in Neil’s right calf, causing a blood flow-preventing clot in early July 2021 that almost resulted in amputation of his foot. Evidently, other debris was lodged within the right middle cerebral artery in his brain, intermittently disrupting the blood flow to a part of his brain tissue and resulting in small ischemic strokes. The diagnosis was confirmed by obtaining and interpreting a combination of tests, including brain MRI, EEG, CT, and eventually, performing a cerebral angiogram, which verified the blockage was caused not by a regular blood clot but by rock-like small fragments of calcium.

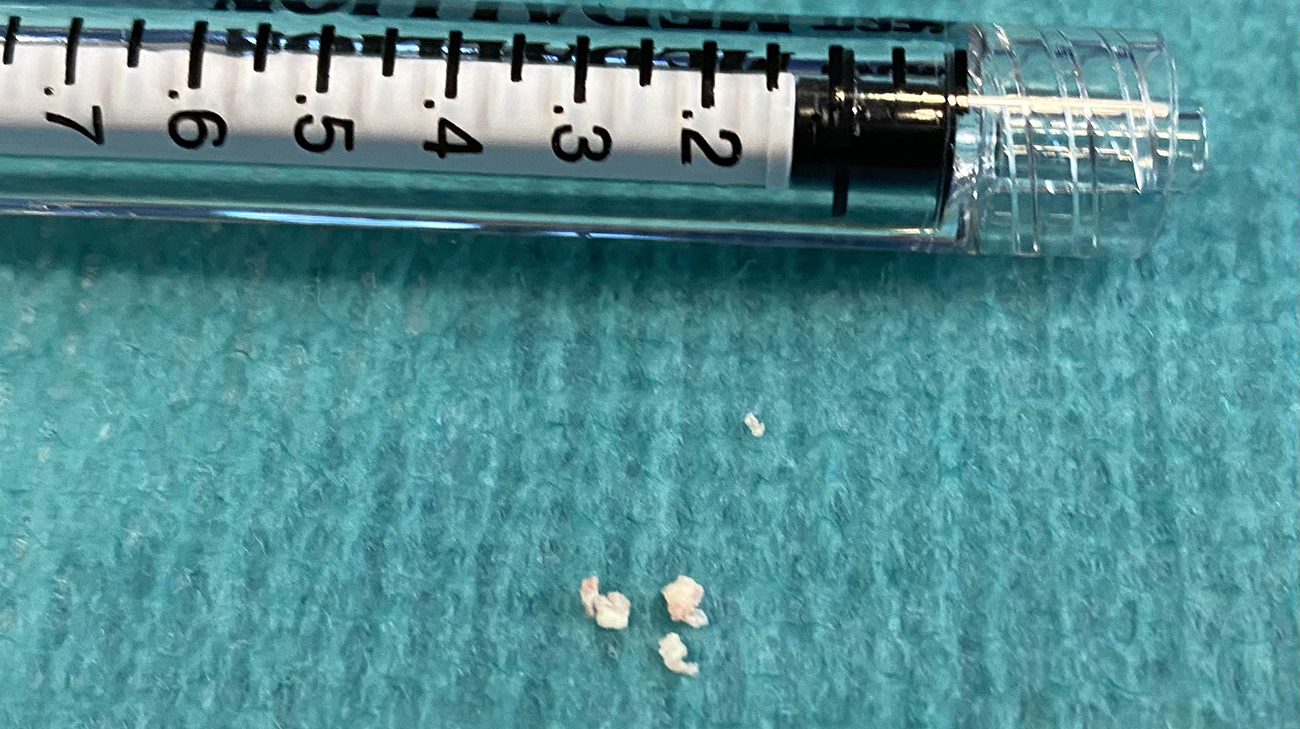

Calcifications removed from Neil's right middle cerebral artery. (Courtesy: Cleveland Clinic)

That discovery likely saved Neil’s life. If he had undergone another heart valve replacement with the brain issue unresolved, spikes in his blood pressure or the use of blood thinners required for the operation could have caused him to experience a major ischemic and/or hemorrhagic stroke.

Confirming the source of Neil’s strokes didn’t solve a major issue for interventional neurologist Gabor Toth, MD, who said the instruments and devices he normally uses to remove blood clots aren’t specifically designed to address the rare occurrence of calcium debris caught in a brain artery.

Neil during a follow-up appointment with Dr. Buletko. (Courtesy: Cleveland Clinic)

“Blood clots are softer, and our tools are more geared towards their composition and texture,” explains Dr. Toth. “In Neil’s case, I had to choose a method that would give me the highest chance of grabbing (the calcium debris), or sliding past it, without it breaking apart. If it did, we’d be chasing the calcium fragments throughout his brain.”

Dr. Toth devised a procedure to extract the calcium deposits from the brain artery by combining two devices -- a special stent retriever with a 3-dimensional inner self-expanding “basket” and an adjacent suction aspiration catheter to hopefully capture the debris and prevent it from breaking apart and floating away prior to removal. Fortunately, the innovative approach was a success.

“It all came out in one pull,” adds Dr. Toth. “There were three or four pieces that we identified after the extraction, but they all came out together.”

Dr. Buletko conducting tests with Neil during a follow-up appointment after Neil's heart and brain surgeries. (Courtesy: Cleveland Clinic)

Two days later, the faulty aortic valve was replaced with a valve from a human cadaver. That surgery was performed by thoracic and cardiovascular surgeon Shinya Unai, MD, who Dr. Toth credited with assembling the multidisciplinary team that collaborated in devising – and executing – the plan that ultimately identified and addressed Neil’s vexing medical conditions. Neurologist, Andrew Russman, DO, and cardiac imaging specialists Rhonda Miyasaka, MD, and Christine Jellis, MD, PhD, were some of the specialists included in Neil’s care.

In the months since both surgeries were performed, Neil has had no new instances of mini-strokes, strokes or heart valve issues. “When he was admitted, it wasn’t exactly clear at first what was happening,” notes Dr. Toth. “But having several specialties and teams working together allowed us to think outside the box. And that certainly made a big difference for Neil.”

Related Institutes: Neurological Institute, Heart, Vascular & Thoracic Institute (Miller Family)