Easter morning in 2020, at home with his family in Warren, Ohio, Patrick Parry experienced a pretty severe case of indigestion. His wife, Melissa, a nurse, suggested he treat it with an over-the-counter antacid medication. With no previous history of heart problems, he certainly didn’t think he was experiencing something more severe, like a heart attack.

“Melissa asked me to rate the pain, from one to 10, and I said it was about a four,” recalls Patrick, then 51-years-old. “I thought I was probably fine.”

While the pain didn’t get worse in the next hour or two, it didn’t improve, either. That’s when the couple, who have three daughters, considered going to the emergency department. However, they talked themselves out of it, a decision impacted by the looming COVID-19 pandemic that was just beginning to accelerate. In fact, a Cleveland Clinic survey found 85% of Americans are concerned about contracting COVID-19 when seeking treatment for health issues at a doctor’s office.

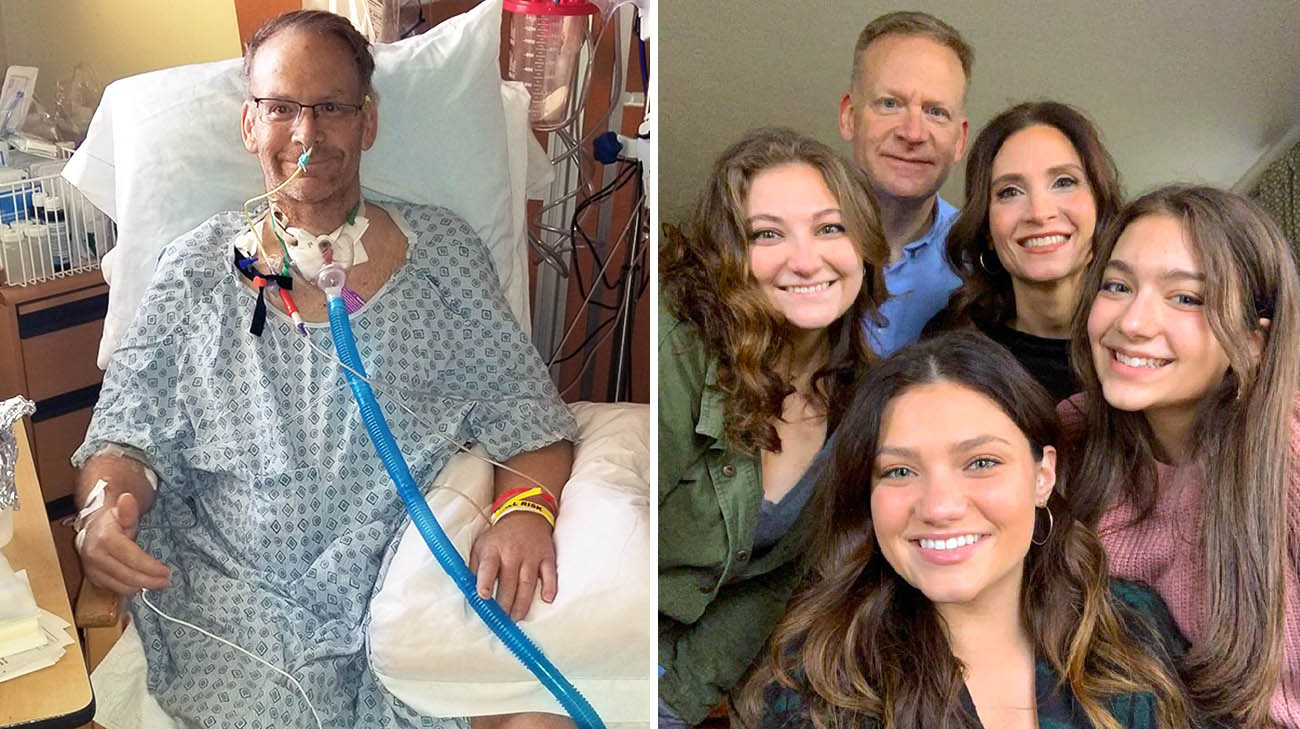

Patrick with his wife, Melissa. (Courtesy: Patrick Parry)

Melissa, guilt-ridden to this day about not urging Patrick to go the emergency room, says, “In hindsight, I think I knew something was wrong, but I just pushed that thought down. We kept going back and forth about it, but we didn’t want to expose us all to COVID or ruin Easter for the kids if it was nothing.”

Adds Patrick, “We decided to take a ‘wait and see attitude’ about going to seek treatment. We’d see how the day went. If it got worse, we’d go.” It got worse. Much worse.

Later that morning, Patrick went to use the bathroom. When he didn’t return for several minutes, Melissa checked to see if he was OK. She discovered him on the floor of their first-floor powder room, nearly unconscious, his complexion ashen.

With the help of a friend who was staying with the family, Melissa dragged Patrick out of the tiny room. She immediately began performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), while waiting for paramedics to arrive.

Patrick with his wife, Melissa, and their three daughters. (Courtesy: Patrick Parry)

“As a nurse, I’ve done CPR before, so I just did what I knew to do, almost on autopilot,” she says. Once the quick-arriving paramedics took over, Melissa let her emotions flow. “I could see he was fighting hard to stay alive. I just kept talking and screaming him through it, over and over: “’Stay with us! This is not how our story ends.’” Patrick was barely able to mouth the words, “I love you,” to his wife.

Upon arriving at a nearby hospital, Patrick was soon rushed into surgery. During a six-hour coronary angioplasty procedure, the surgeon inserted several stents, or small mesh tubes, used to open clogged arteries, enabling the blood to travel more freely through his body.

Waiting nervously nearby were Melissa and their eldest daughter, 25-year-old Hannah. They were the only two non-medical personnel inside the hospital at the time, which was otherwise shut to visitors due to the raging coronavirus pandemic.

While Patrick was alive, he wasn’t yet out of the woods. He suffered sepsis, an infection of the blood stream, and kept spiking high fevers. After a few days, his condition was stable enough to transfer him by ambulance 65 miles northwest to Cleveland Clinic

Patrick spent two months in the hospital. He was unconscious for one month. (Courtesy: Patrick Parry)

“The (first) hospital did a great job, but it was a huge case and a dismal situation,” adds Melissa, who wouldn’t see Patrick in person for the next four weeks. “He would not be alive today if we had not made the choice to move him. We’re so blessed to have Cleveland Clinic just an hour away.”

According to Cleveland Clinic cardiologist Heba Wassif, MD, one of several clinical caregivers involved in Patrick’s treatment, his heart attack was caused by coronary artery disease (CAD), the narrowing or blockage of the arteries that supply blood to the heart.

“There is a misunderstanding that the only symptom for heart attack is a chest pain that goes up the neck and down the arm,” she states. “Patients with CAD can present with a multitude of symptoms, and heartburn is one of them.

“Time is muscle,” Dr. Wassif adds. “The longer you wait, the more complications you are likely to have.”

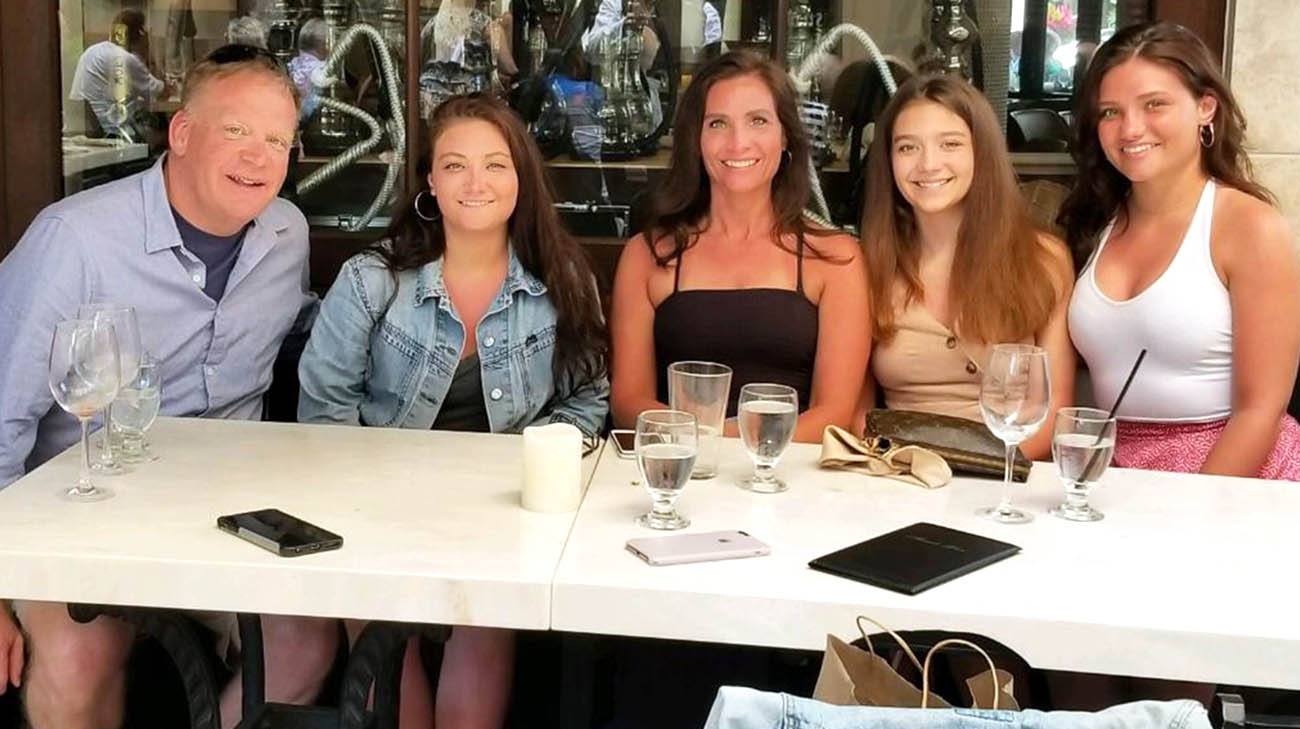

After moving out of the ICU and a rehabilitation hospital, Patrick continued recovering at home. (Courtesy: Patrick Parry)

Patrick had plenty of complications. During his hospital stay, he had another heart attack, was placed on a ventilator and underwent a tracheotomy in order to receive adequate oxygen. Although unconscious, his condition slowly improved with the help of several medications.

Nevertheless, Melissa – while hopeful – understood Patrick might never awaken, and if he did, he might not have normal brain function. Thus, she was pleasantly shocked one day, several weeks after his heart attack, when a Cleveland Clinic caregiver connected with her with Patrick via FaceTime.

“She turned the camera, and there Pat was, awake, eyes open, looking straight at me. The nurse is sobbing, and his room is full of people who worked so hard for Pat to get better,” Melissa recalls. “That was a very good day.”

More good days would ensue. Soon after, Patrick moved out of the ICU, and ultimately to a long‑term acute care rehabilitation hospital. His recovery continued once he returned home. By June 2020 he was able to return to his law practice, nearly full-time.

Patrick slowing transitioned back to working as an attorney, weeks after experiencing a heart attack. (Courtesy: Patrick Parry)

Patrick, now 52, feels lucky to have survived his ordeal, but laments that many of the most severe consequences of his condition may have been avoided if he’d gone to the hospital earlier that Easter morning. He’s not alone in delaying treatment. The Cleveland Clinic survey also found 52% of respondents overall and 65% of heart disease patients have put off health screenings or check-ups because of the pandemic.

“Don’t make the same mistake I made,” Patrick implores to anyone experiencing out-of-the-ordinary symptoms. “If you have any question that an issue might be serious, put COVID out of your mind and take action. Don’t let that be an excuse to rationalize your decision not to seek treatment.”

Dr. Wassif agrees, “Since the start of the pandemic, the number of people presenting to the hospital with heart attacks has been down. This was clearly not because people were having less heart attacks, but that they were not going to the hospital. People must not delay in seeking medical attention.”

Related Institutes: Heart, Vascular & Thoracic Institute (Miller Family)