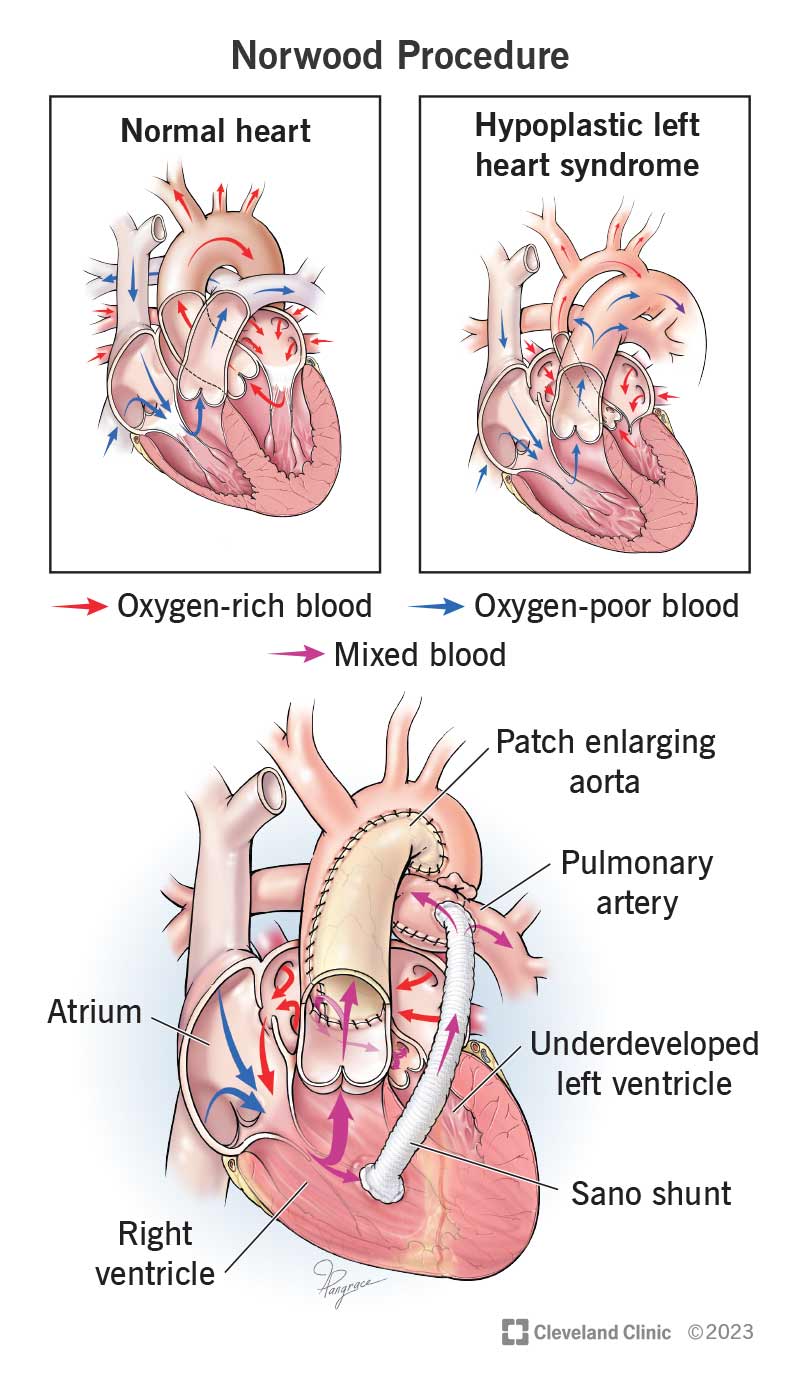

A Norwood procedure improves blood circulation in a baby born with hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS). This operation lets a baby’s right ventricle take over for an underdeveloped left ventricle and aorta. After surgery, their right ventricle pumps blood to their lungs to get oxygen. It also pushes blood with oxygen to their entire body.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/24794-norwood-procedure)

A Norwood procedure is an operation surgeons perform most commonly for a baby born with hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS). This surgery lets the right side of a baby’s heart send blood with oxygen to their body. Normally, your heart’s left side takes care of this. In a baby with HLHS, their heart’s left side isn’t developed enough to do it.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

After this surgery, your baby’s right ventricle (lower heart chamber) still does its normal job of pumping blood without oxygen to their lungs. However, it also does the left ventricle’s job of sending blood with oxygen to their body.

This doesn’t keep the blood with oxygen separated from the blood without oxygen like in a normal heart. It’s not a perfect solution. However, it’s an improvement that helps deliver more oxygen to your baby’s cells and tissues.

Babies with hypoplastic left heart syndrome need to have this surgery in the first weeks of life. The Norwood procedure helps their right ventricle do the work of both ventricles. Babies with HLHS need this because their left ventricle didn’t develop completely.

For the first few days after birth, your baby’s blood can move between their aorta and pulmonary artery through their patent ductus arteriosus. This allows their right ventricle to send blood to their lungs and their body. But when this opening closes naturally soon after birth, their right ventricle can’t send blood to their body anymore.

Medicine can keep their patent ductus arteriosus open for a while. However, a Norwood procedure provides an interstage solution that lets the baby’s working ventricle (the right one) do all of their heart’s pumping.

Advertisement

Some children aren’t good candidates for a Norwood procedure because they were preterm babies, are small for their gestational age (SGA) or have other major issues. In these cases, pulmonary artery bands can reduce how much blood goes to their lungs and increase how much blood goes to their body.

Norwood procedures aren’t common. Surgeons performed about 250 Norwood operations between 2015 and 2018, according to a North American database with more than 1,000 participating providers.

About 1,000 babies a year are born with hypoplastic left heart syndrome in the United States. Many of these babies with HLHS could be candidates for a Norwood procedure.

If your baby has hypoplastic left heart syndrome, they’ll receive medicine soon after birth. This medicine prevents your child’s patent ductus arteriosus from closing like it normally does. Keeping it open allows for more blood flow through their heart until they have Norwood heart surgery.

Also, a provider may perform a septostomy to enlarge an opening between the two upper chambers (right and left atrium) to improve the flow of blood from the lungs into the right side of the heart.

A Norwood operation is a complex surgery with many steps. Here’s a simplified description of what the surgeon will do.

Your child’s surgeon will make an opening in the wall between your baby’s left and right atria. This lets blood flow between them and allows blood coming back from their lungs to reach their right ventricle. The surgeon connects the small aorta to the larger pulmonary artery and then uses a patch to make your child’s aorta larger. The surgeon will then connect their improved aorta to the right ventricle.

Another part of this surgery involves putting a tube or shunt between your child’s aorta or other major artery and their pulmonary arteries (Blalock-Taussig or BT shunt). The pulmonary arteries take blood to your child’s lungs. The other option (called a Sano shunt) is to put a tube between their right ventricle and their pulmonary arteries.

Your child will be on cardiopulmonary bypass during their Norwood operation. That means a machine will take care of circulating oxygenated blood to their body and their brain.

A Norwood procedure takes many hours. It can take as long as a day’s full-time shift at work.

Your baby will be in the intensive care unit (ICU) after surgery. After one week there, they’ll move your baby to a regular hospital room.

You’ll see tubes and equipment that are there to help give your baby what they need. They’ll have a bandage in the middle of their chest after Norwood surgery.

Advertisement

Although this surgery helps your baby’s blood circulation, it’s not a cure. Blood with and without oxygen can still blend in their heart. Because of this, your baby may still have a blue tint to their skin.

Your provider will give you instructions for how to care for your baby when you bring them home. Most hospitals have special clinics that offer follow-up care that includes a home monitoring program. Look for a program that provides multidisciplinary care through adulthood.

The three surgeries for HLHS are:

The Norwood procedure gives babies with HLHS a chance to live. With two follow-up surgeries, they can survive infancy and even become teens and young adults. Before surgeons started doing Norwood operations in the early 1980s, there was no surgical treatment for babies born with HLHS.

Norwood procedure complications include:

Your child will be in the hospital for seven to 21 days after surgery. Some of this time will be in the intensive care unit.

Advertisement

In-hospital survival for the Norwood procedure is 90%. The five-year Norwood procedure survival rates range from 60% to 75%. HLHS can suddenly become fatal for some children, and they won’t make it to the second surgery stage.

Six years after surgery, 60% of children survive without a heart transplant. The survival rate is about the same 20 years after surgery.

The prognosis tends to be worse for babies who had a low birth weight, are preterm or who have other types of congenital disorders (disorders from birth) that don’t involve the heart.

Contact your child’s provider if:

Your child will need to see their cardiologist regularly throughout their lifetime, especially between surgeries.

Since HLHS is a rare condition, it’s best to find a provider who has done the Norwood procedure many times. Don’t be afraid to ask questions about anything you don’t understand about your child’s surgery.

Advertisement

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

If your child has hypoplastic left heart syndrome, you want expert, compassionate help. At Cleveland Clinic Children’s, we offer the best care for your family.