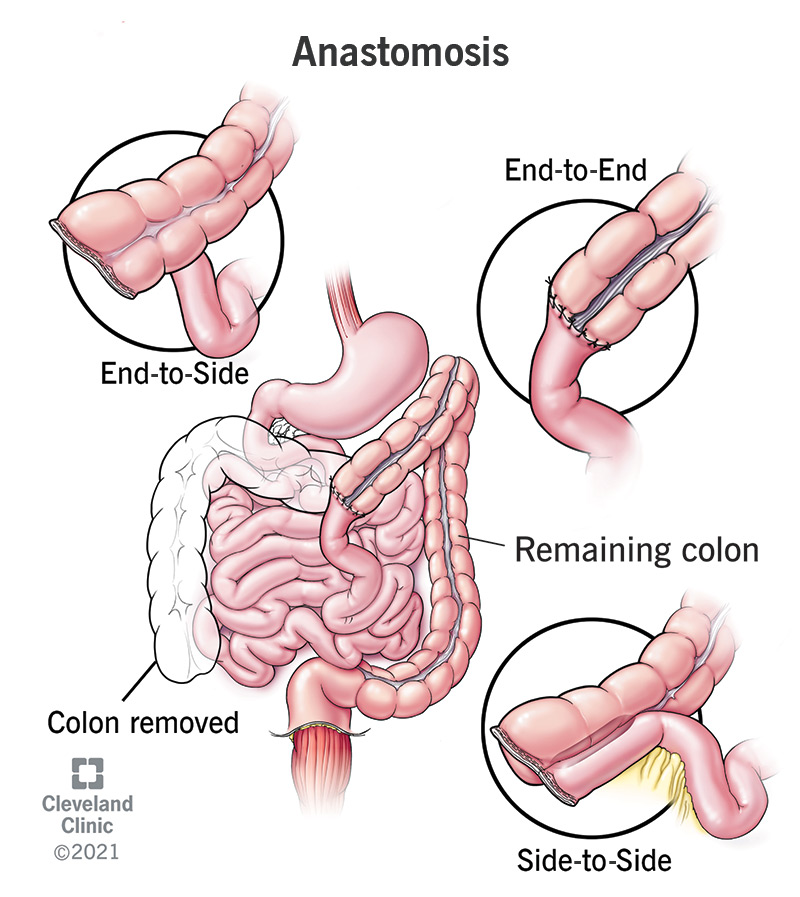

An anastomosis is a surgical connection between two tubes in your body, like your intestines or blood vessels. Surgeons sometimes create these connections to restore normal flow after removing damaged tissue. Other times, they use these procedures to bypass a blockage and create a new pathway.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/24035-anastamosis.jpg)

An anastomosis (uh-NAS-toh-MOH-sis) is a surgical connection between two tubes in your body. This could be between two blood vessels or between two parts of your intestines. Those are the most common types, but there are many others.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Your body already has natural connections like this. But a surgeon may need to create a new connection. This often happens after removing damaged or diseased tissue.

By joining the healthy ends together, your surgeon can help restore normal flow. If there’s a blockage, they may create a new pathway that goes around it.

Types of surgical anastomosis include:

Some common examples include:

Advertisement

If you have inflamed tissue due to disease or infection, your surgeon may wait before creating a surgical connection. This gives the tissue time to heal.

In some cases, your surgeon will create an ostomy instead. This diverts waste to an opening in your belly. There, it drains into an ostomy bag.

Surgeons can connect tubes in your body in a few different ways. They may use:

All surgical procedures carry certain standard risks, including:

There are two complications specific to anastomosis surgery: anastomotic strictures and anastomotic leaks.

An anastomotic stricture happens when scar tissue forms at the surgical connection and narrows the tube. This can slow down or block the movement of food, pee or other fluids.

Stenosis can also occur in the neck of your bladder after prostate surgery. It occurs when your urethra is connected to your bladder neck. This is called bladder neck contracture.

In both cases, healthcare providers can often treat the stricture by widening it with a balloon, or with tubes.

An anastomotic leak happens when the new connection doesn’t seal completely. This allows fluids or waste to leak into nearby tissue.

This is serious because these substances can damage your body if they leak out. For example, bacteria from your intestines can cause an infection if they leak into your belly.

After surgery, you’ll spend time in the hospital so your care team can watch your recovery. How long you stay depends on the type of surgery you had and how well you heal.

At first, you may not be able to eat or drink normally. Your healthcare providers will slowly reintroduce liquids. Then, you can start solid foods as your body heals. They’ll also watch for signs of problems. These could be infections or leakage at the surgical connection.

You may have pain, swelling or tiredness while you recover. Your providers will give you medicine and instructions to help manage your discomfort. Most people can slowly return to normal activities over time. Full recovery may take several weeks.

Call your healthcare provider right away if you notice any of the following symptoms after surgery:

Advertisement

These symptoms may be signs of a complication. Your provider should check them out as soon as possible.

Creation of an anastomosis is an important part of many surgical procedures. It’s what makes many of these procedures possible. As a result, it’s also a cornerstone of surgical training. Surgeons have many tools and techniques at their disposal to make your anastomosis successful and to manage complications when they occur. Most succeed without complications.

If you do have a leak, early intervention can control it and prevent further complications. If you develop a stricture, nonsurgical methods can often treat it.

Advertisement

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Sometimes you have surgery planned. Other times, it’s an emergency. No matter how you end up in the OR, Cleveland Clinic’s general surgery team is here for you.