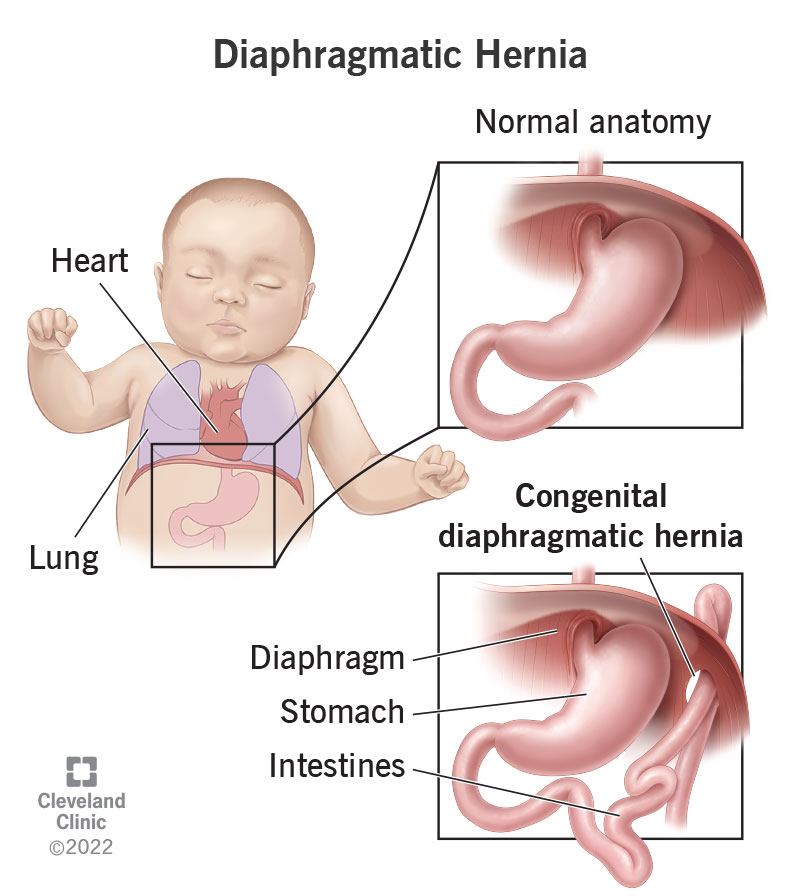

A congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) is a type of hernia that occurs during fetal development. When abdominal organs move into a fetus’s chest, they can crowd its lungs. Babies born with CDH tend to have small, underdeveloped lungs and low blood oxygen. They’ll need immediate oxygen support and surgery to repair the hernia.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/24308-diaphragmatic-hernia)

A congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) is a birth defect that occurs during fetal development. It means that a fetus’s diaphragm isn’t fully formed or strong enough to be a muscle barrier between its belly (abdomen) and chest. That means organs can pass between them. When an organ passes through a muscle barrier, it’s called a hernia.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

When a diaphragmatic hernia occurs during fetal development, it affects the way the fetus’s body forms. Its abdominal organs — the stomach, intestines, liver, gallbladder, pancreas and spleen – can shift upward into the chest cavity while everything is still developing. When this happens, the extra organs in the fetus’s chest can end up crowding its lungs and prevent them from growing normally.

Babies born with CDH tend to have small, underdeveloped lungs (pulmonary hypoplasia) . This can cause low blood oxygen levels and breathing difficulties at birth. They’ll also have high blood pressure in their lungs, which puts stress on their heart. These babies need critical care at birth to stabilize their condition.

Video content: This video is available to watch online.

View video online (https://cdnapisec.kaltura.com/p/2207941/sp/220794100/playManifest/entryId/1_zozjowsf/flavorId/1_5f3sgelj/format/url/protocol/https/a.mp4)

Learn about congenital diaphragmatic hernia from Miguel Guelfand, MD.

Severe difficulty breathing is the first sign that an infant has CDH. Other congenital diaphragmatic hernia symptoms may include:

Physicians don’t know the exact cause of CDH. Research suggests the following factors may play a role in its development:

Advertisement

Most infants born with a congenital diaphragmatic hernia have small and underdeveloped lungs (pulmonary hypoplasia). This can cause a variety of difficulties, including:

Infants with CDH may also have:

Your healthcare provider may find a congenital diaphragmatic hernia during a routine prenatal ultrasound. After discovery, your provider will follow up with a fetal MRI to see the hernia more clearly. They’ll also take a fetal echocardiogram to find out if the fetus’s heart is affected.

Sometimes, your provider doesn’t see a CDH until after your baby is born. Your delivery team may notice signs of respiratory distress or unique body features, like an uneven chest or a barrel chest with a small or concave abdomen. Your providers will follow up with a chest X-ray and an echocardiogram. They may want to take a blood sample to test your baby’s blood oxygen levels and to look for other genetic anomalies.

Rarely, babies born with CDH have no noticeable symptoms. If the hernia is small and causes no major symptoms, healthcare providers may not discover it until later in childhood, or even adulthood.

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia treatment begins as soon as your healthcare provider diagnoses it. These treatments may seem scary, but your healthcare provider is doing everything they can to keep your baby safe.

If your healthcare provider discovers CDH during your pregnancy, they’ll monitor you closely. They’ll look for congenital issues in other organ systems that can be part of a more complex disease. Your provider will also watch for signs of premature labor and decide whether they need to induce your labor early for the sake of the fetus.

Advertisement

In some cases, your healthcare team may be able to treat the fetus before birth. Fetoscopic tracheal occlusion (FETO) is a fetal surgery that, in very specific cases, can help improve the size and function of the fetus’s lungs while it’s still growing. Your provider may use a minimally-invasive surgery called a fetoscopy. A fetoscopy uses a tiny lighted camera called a fetoscope to view the fetus through small cuts (incisions) through your skin and into your uterus.

Through FETO, your provider places a balloon in the fetus’s trachea (windpipe). This allows the amniotic fluid it breathes to build up in its lungs behind the balloon, causing its lungs to expand. This expansion can improve the growth and function of the lungs and reverse some of the damage CDH caused.

Babies who are born with CDH usually require immediate intensive care by a specialized team. If your baby is born with pulmonary hypoplasia (underdeveloped lungs), they’ll need oxygen support first. For some babies, this means a breathing tube attached to a mechanical ventilator.

Other babies may need a more aggressive life support called extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). This is a way of bypassing your baby’s underdeveloped lungs and, sometimes, their heart. ECMO draws blood from an artery or vein and adds oxygen to the blood in a machine before sending it back into your baby’s circulation.

Advertisement

Next, your baby will need surgery. Your baby will remain in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) until your healthcare team determines that it’s safe to consider surgery. This usually means that pulmonary hypertension has improved and your baby no longer needs ECMO.

For the surgery, a pediatric anesthesiologist will put your baby to sleep with anesthesia. A pediatric surgeon will operate on your baby to move their organs back into their abdomen and repair the defect in their diaphragm. In almost half of all cases, surgeons can use minimally invasive surgery (MIS) through micro 3 mm cuts (incisions) instead of open surgery.

As your baby recovers from surgery, they’ll begin to come off oxygen support. They’ll receive nutrients through a tube until their provider removes the breathing tube. After that, speech and lactation specialists can work with you and your baby to begin mouth feeding. Some babies take longer than others to transition from oxygen support and tube feeding. Your healthcare team will work with you for as long as necessary.

The reported survival rate for babies born with CDH has improved. Between 7 and 9 out of every 10 babies survive. These babies are born critically ill, but for those who make it through the tense early days of their condition, the outlook gets better. Some children may have long-term complications, but they’ll still live long and full lives. Continuing advances in medicine improve the odds of both short-term survival and long-term health.

Advertisement

The longer-term prognosis depends on several factors, including:

Babies who require breathing or feeding support for longer have a higher risk of ongoing complications, including chronic lung disease, growth failure, hearing loss and developmental delays. Your child’s provider will monitor them closely throughout their early life.

It can be scary and confusing to learn your baby has a congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Immediately after birth, your baby will be whisked away for intensive care and possibly a long hospital stay. But through advances in medicine, the prognosis for CDH is better than ever. Though this is a difficult time, you and your newborn will have a team of healthcare providers looking out for you. They’ll support you at every step from the moment of diagnosis through your child’s early life.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Prenatal tests can give your providers information about your pregnancy and fetal development. Cleveland Clinic’s experts can guide you through prenatal testing.