The mesentery is structure in the back of your abdominal cavity, composed mainly of connective tissues. It supports your intestines and connects to several other organs, sharing blood vessels, lymph nodes and nerves with them. New research suggests that the mesentery plays a more important role in your digestive system than previously thought.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/Images/org/health/articles/mesentery.jpg)

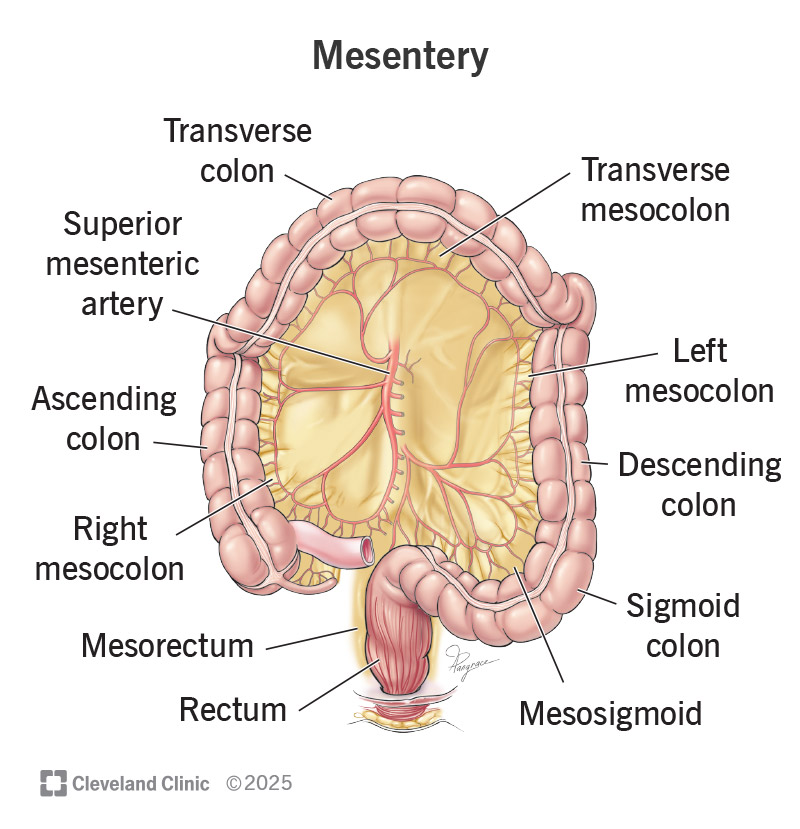

The mesentery is a fold of tissue inside your abdomen. It connects your intestines to the back wall of your belly and attaches to organs like your liver, spleen and pancreas. It carries blood vessels, lymph vessels and nerves that serve these organs.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Healthcare providers now see the mesentery as more than just tissue — some even classify it as an organ. That’s because it’s one continuous structure with a clear purpose to support, nourish and connect several digestive organs.

Researchers are still learning, but they know the mesentery:

It begins at the back of your abdomen, near a major blood vessel called the superior mesenteric artery. From there, it extends in a spiral shape that covers your intestines.

The adult mesentery is about 6 feet long when stretched out.

The mesentery is one continuous organ, but different sections branch out to connect with various other organs. Some parts anchor your intestines to the back of your abdominal wall, while others secure organs without fixing them in place. This keeps the organs stable but still allows some movement.

Advertisement

It’s easiest to understand the mesentery by looking at its attachments. These include several parts once thought to be separate:

Doctors once thought these were separate structures, but now we know they are all part of one mesentery. This discovery changes how we understand development and surgery.

It’s mostly fat tissue, along with connective tissue, blood vessels, lymph tissue and nerves. A protective layer called the mesothelium surrounds it, and another tissue, Toldt’s fascia, connects it to the abdominal wall.

Much research links the mesentery to Crohn’s disease, an inflammatory bowel disease. Some studies suggest Crohn’s may even start in the mesentery.

Most belly fat is stored here as visceral fat. Too much visceral fat raises the risk of:

Other diseases and conditions involving the mesentery include:

Because it’s tied to so many organs, many digestive diseases also involve the mesentery.

New research shows that surgeries on abdominal organs often need to include the mesentery. For example, removing parts of the mesentery may slow Crohn’s disease or reduce the risk of colon cancer coming back.

This growing knowledge is also changing surgery itself. In the past, surgeons treated the abdomen as a collection of sacs, pouches and cavities with multiple mesenteries. Now, they divide it into two regions — one that includes the mesentery and one that doesn’t. This simpler view can make abdominal surgery more straightforward.

Advertisement

The best way is to keep a healthy amount of visceral fat. Too much raises the risk of chronic disease. You can lower visceral fat by:

You may not think much about whether the mesentery is called an “organ” or “tissue.” But for doctors and researchers, that language matters. Seeing the mesentery in a new way changes how they study, diagnose and treat digestive diseases. It even shapes how surgeons approach abdominal surgery.

The good news for you is that each new discovery brings us closer to understanding how this hidden structure supports your health — and how we can better protect it.

Advertisement

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic's health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability, and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic's health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability, and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s primary care providers offer lifelong medical care. From sinus infections and high blood pressure to preventive screening, we’re here for you.