Median arcuate ligament syndrome (MALS) is a very rare disease in which the median arcuate ligament presses on your celiac artery and nearby nerves (celiac plexus). A common symptom is intense pain in your upper belly that usually happens after you eat. Treatment is surgery to separate the ligament from the celiac artery and celiac plexus.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/Images/org/health/articles/16635-median-arcuate-ligament-syndrome-mals.jpg)

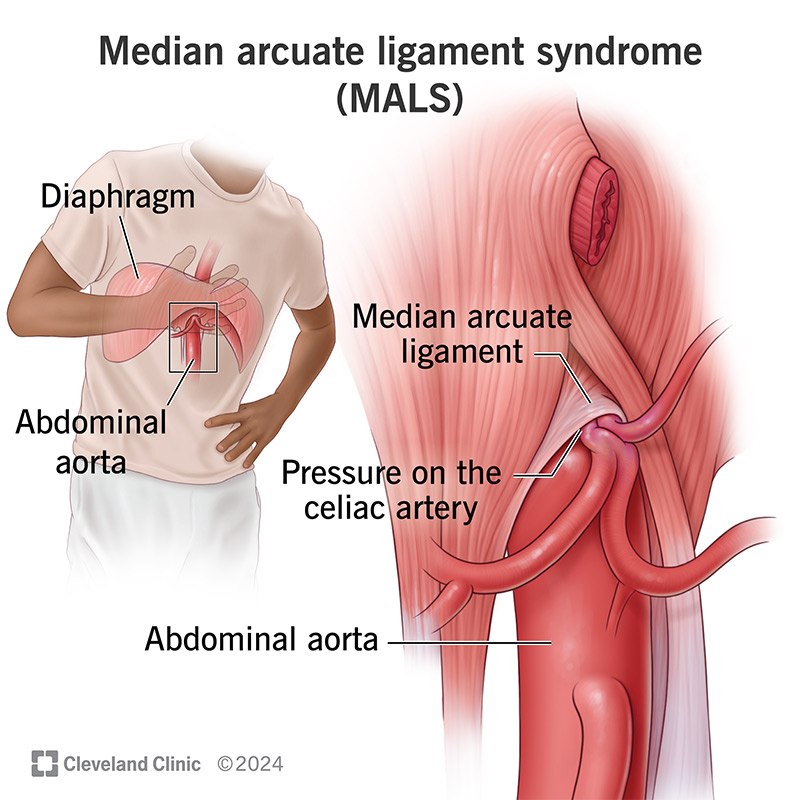

Median arcuate ligament syndrome (MALS) refers to a condition that happens when the median arcuate ligament in your chest presses against your celiac artery and nearby nerves (celiac plexus).

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Your median arcuate ligament is shaped like an arch and goes around your aorta. Your aorta sends blood from your heart to the rest of your body, and your celiac artery is a major branch of your aorta.

Normally, your median arcuate ligament sits above your celiac artery. In MALS, your ligament is lower than usual. When it presses on your celiac artery, the pressure keeps blood from flowing through your celiac artery. It may also put pressure on nearby nerves.

When that happens, you develop pain in your upper abdomen that comes on after you eat. The pain may be so intense that you start avoiding food. Other names for MALS are:

Upper abdominal pain that happens after you eat is the first symptom of MALS. The pain may be so intense that you’re afraid to eat for fear that food will trigger symptoms. Other symptoms are:

Experts don’t know the exact reason why it happens. Some researchers suggest people are born with a median arcuate ligament that’s not in the right place. Another theory is MALS is a complication of abdominal or spinal surgery or abdominal trauma.

Advertisement

Often people have the condition for months or years before receiving a MALS diagnosis. In the meantime, they’re living with chronic pain, which can lead to mental health issues like depression. They may also develop anxiety when tests don’t lead to diagnosis and treatment.

If your healthcare provider thinks you may have MALS, they’ll review your medical history and perform a physical exam.

Many diseases cause pain in your upper abdomen, from appendicitis to gastroparesis to peptic ulcer disease. Your provider may order different blood tests and imaging tests to rule out more common conditions that may cause your symptoms.

Your provider may order one or more of the following blood tests:

If these tests rule out common conditions, your provider may refer you to a gastroenterologist for more tests, including:

Your healthcare provider may recommend a celiac plexus block to help ease stomach pain. They may recommend median arcuate ligament release, which is surgery to remove or release your ligament so it’s not pressing on your celiac artery. This procedure restores blood flow through your celiac artery and removes pressure on nearby nerves.

MALS is an unusual disease that causes physical and mental health issues. So, you can expect to have a whole team of specialists working to help you find relief, including:

Surgery often eases symptoms. But research shows median arcuate ligament syndrome can come back after surgery. You can’t keep that from happening. But knowing what changes in your body may mean MALS is back may help. Ask your healthcare provider about early changes. They’ll be glad to explain what may be signs of trouble.

MALS symptoms can come back after surgery. You should contact your care team if that happens.

Advertisement

You know something is going on in your gut. Misery, in the form of intense upper belly pain, follows every meal. But time after time, tests don’t pinpoint the problem, much less treatment. You may hear your symptoms have more to do with your mental health than physical health. For those reasons, you may feel relieved to learn the rare condition median arcuate ligament syndrome is responsible for your symptoms.

Better yet, there’s treatment to ease your pain, and your provider may recommend surgery. If the diagnosis is MALS, your healthcare team will recommend treatment and help you get back to enjoying meals and your life.

Advertisement

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s primary care providers offer lifelong medical care. From sinus infections and high blood pressure to preventive screening, we’re here for you.