Frozen shoulder, also called adhesive capsulitis, is a condition involving pain and stiffness in your shoulder joint. Symptoms usually start slowly and get worse over time. But within one to three years symptoms typically get better. Your risk for developing frozen shoulder increases if you must keep your shoulder still for a long time.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/frozen-shoulder)

Frozen shoulder is a painful condition in which your shoulder movement becomes limited. Another name for frozen shoulder is adhesive capsulitis.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

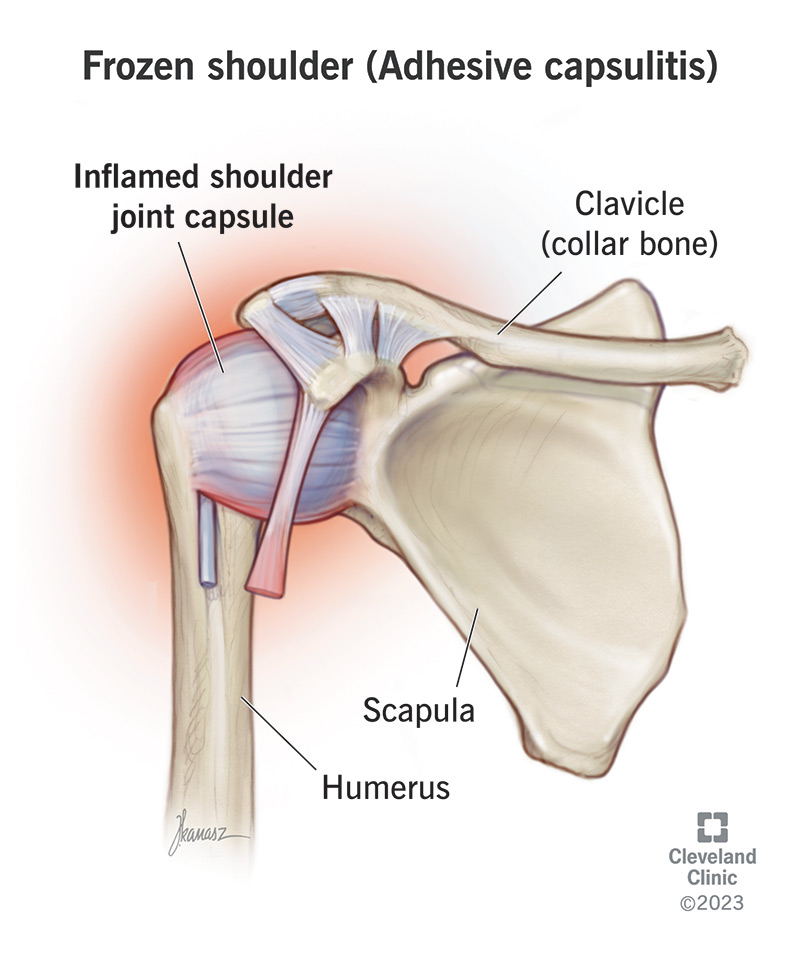

Frozen shoulder occurs when the strong connective tissue surrounding your shoulder joint (called the shoulder joint capsule) becomes thick, stiff and inflamed. The joint capsule contains the ligaments that attach the top of your upper arm bone (humeral head) to your shoulder socket (glenoid), firmly holding the joint in place. This is more commonly known as a ball-and-socket joint.

The condition is called “frozen” shoulder because the more pain you feel, the less likely you’ll use your shoulder. Lack of use causes your shoulder capsule to thicken and become tight, making your shoulder even more difficult to move — it’s “frozen” in its position.

Healthcare providers divide frozen shoulder symptoms into three stages:

Advertisement

Researchers don’t know exactly why frozen shoulder develops. The condition occurs when inflammation causes your shoulder joint capsule to thicken and tighten. Thick bands of scar tissue called adhesions develop over time, and you have less synovial fluid to keep your shoulder joint lubricated. This makes it more difficult for your shoulder to move and rotate properly.

The following risk factors increase your likelihood of developing frozen shoulder:

To diagnose frozen shoulder (adhesive capsulitis), your healthcare provider will discuss your symptoms and review your medical history. They’ll also perform a physical exam of your arms and shoulders. They’ll:

Your provider will likely order shoulder X-rays to make sure the cause of your symptoms isn’t due to another problem with your shoulder, like arthritis. You usually don’t need advanced imaging tests like magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasound to diagnose frozen shoulder. But your provider may request them to look for other problems, like a rotator cuff tear.

Frozen shoulder treatment usually involves pain relief methods until the initial phase passes. You may need therapy or surgery to regain motion if it doesn’t return on its own.

Some simple adhesive capsulitis treatments include:

Advertisement

If these noninvasive treatments haven’t relieved your pain and shoulder stiffness after about a year, your provider may recommend other procedures. These include:

Advertisement

Providers often use these two procedures together to get better results.

Simple treatments, like the use of pain relievers and shoulder exercises, in combination with a cortisone injection, are often enough to restore motion and function within a year or less. Even left completely untreated, range of motion and use of your shoulder continue to get better on their own, but often over a slower course of time. Full or nearly full recovery is seen after about two years.

You can reduce your risk of frozen shoulder if you start physical therapy shortly after any shoulder injury in which shoulder movement is painful or difficult. Your orthopedic surgeon or physical therapist can develop an exercise program to meet your specific needs.

Frozen shoulder (adhesive capsulitis) can be a debilitating condition to live with. The pain and stiffness in your shoulder joint can make it difficult or even impossible to perform daily activities that you once did with no problem. If at-home treatments like rest and pain relievers don’t help, reach out to your healthcare provider. They may recommend physical therapy or other noninvasive measures to start. Surgery is an option for frozen shoulder that doesn’t go away after an extended period. Your provider can help you find the best treatment option for you.

Advertisement

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Living with constant shoulder pain? Cleveland Clinic can help you get the relief you need with personalized treatment plans that match your needs.