Pectus excavatum is an abnormally developed breastbone. This makes an indentation in your chest wall that can cause physical and emotional issues. Open or minimally invasive surgery can treat pectus excavatum, allowing you to breathe better and have more stamina. Mild cases don’t need surgery.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/17328-pectus-excavatum)

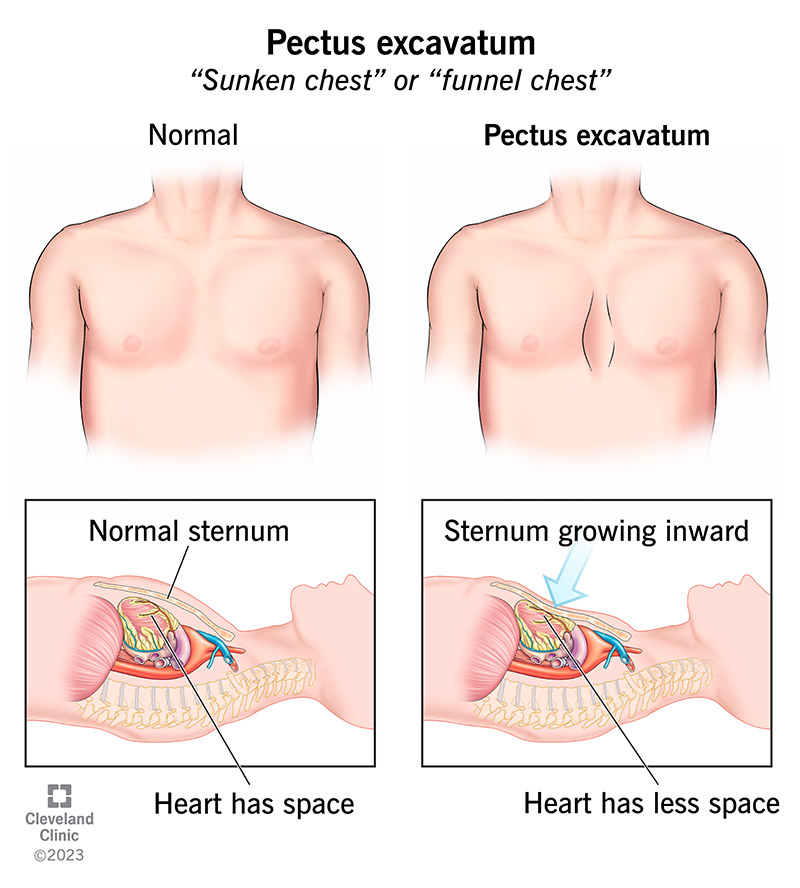

Pectus excavatum is an abnormal, inward-growing sternum (breastbone). This creates a noticeable and sometimes severe indentation of your chest wall that involves four or five ribs per side.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Other names for pectus excavatum are sunken chest or funnel chest. This condition gives you less space in your chest, which can limit heart and lung function.

Pectus excavatum is a congenital condition, which means you’re born with it. But people often notice it during their early teen years.

Healthcare providers can correct pectus excavatum with minimally invasive surgery or traditional open surgery.

Pectus excavatum is the most common congenital (present at birth) abnormality that affects your chest wall. About 1 to 8 people per 1,000 have it. It happens more often in boys.

Pectus excavatum symptoms can be both physical and psychological.

Physical symptoms can include:

Psychological symptoms can include:

For many people, their pectus excavatum causes are unknown. But some people get it as part of a connective tissue disease like Marfan syndrome or Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

Researchers haven’t found a specific genetic link yet. But they suspect there is one. About 40% to 53% of people with pectus excavatum have a biological family member with the same condition.

Advertisement

Without a known cause of pectus excavatum, it’s difficult to pin down risk factors. Still, you may be at a higher risk for pectus excavatum if you have this condition in your family or have a syndrome linked to it.

Pectus excavatum is associated with:

A healthcare provider can diagnose pectus excavatum with a simple physical examination. Providers may not notice the issue until you’re in your early teens. They may want to do testing to see how much pectus excavatum is affecting your cardiopulmonary (heart and lung) function.

Tests for pectus excavatum may include:

A surgeon can correct pectus excavatum with a minimally invasive (Nuss procedure) or an open (Ravitch procedure) operation. Your surgeon will discuss which procedure is best for you. During the surgery, your surgeon repositions your sternum (breastbone) to a more outward position. Both surgeries:

Surgery may be right for you if you’re having physical symptoms and/or psychological symptoms from pectus excavatum. The best time for a pectus excavatum repair is between 10 and 14 years of age, when your chest wall is still flexible. Your provider can help you decide the right time for surgery.

In this minimally invasive procedure, your surgeon will:

The bar stays in place for several years. A surgeon removes it in an outpatient (same-day) procedure.

In this traditional or open procedure, your surgeon will:

A surgeon will remove the bar in six to 12 months during a short outpatient procedure. This bar is smaller than the bar they use in the Nuss procedure. You don’t need additional surgery because surgeons don’t remove the plates.

Advertisement

Like other major surgeries, the surgical repair of pectus excavatum presents risks. Both the Nuss procedure and the modified Ravitch technique are safe and effective procedures. But complications, although rare, can happen.

Possible complications from surgical repair of pectus excavatum include:

With advances in pain management, recovery from surgery is shorter and less painful now than it used to be.

Cryoablation freezes the nerves between your ribs that provide pain sensation to your chest wall. You also receive an injection of local anesthetics (numbing medicine) of those same nerves and oral painkillers before and after surgery.

Using cryoablation to minimize severe pain after the Nuss procedure significantly shortens hospital stays and reduces the need for opioids.

Before cryoablation-assisted Nuss procedures, students had to have surgery in the summer because it took a month or more to recover. Now, they can have surgery during a short break from school because of the shorter hospital stay and recovery time.

Advertisement

Traditional pain management for the Nuss procedure used to require a one-week hospital stay after surgery. It also required epidural anesthesia, followed by several weeks of potentially addicting opioid medication after discharge.

With cryoablation, most people can go home the day after surgery. Some people don’t need any IV or oral (by mouth) opioids in the hospital. Those who do need oral opioids typically stop using them in one to two days. Cryoablation will result in a numb chest wall for six months to one year.

The goal of pectus excavatum repair is to relieve pressure on your heart and lungs so they can work better. This typically improves breathing, exercise intolerance and chest pain. You may feel as if your breathing and stamina are normal before surgery and then realize they feel much improved after surgery.

People whose main issue is the abnormal appearance of their chest have had positive changes in their self-esteem and self-confidence after surgery. For adults with pectus excavatum, limitations on activity may not be obvious until their late 30s or 40s.

You’ll have pectus excavatum until you have an operation to fix it.

After surgery, you’ll need to take it easy for a while due to discomfort. You can walk and run again when discomfort permits. Your surgeon will determine when you can resume heavy lifting and competitive sports.

Advertisement

Students should be able to go back to school two to three weeks after surgery for pectus excavatum.

Both the Nuss and Ravitch procedures have excellent results. People are almost always satisfied with the way they feel and look after recovery. The rate of the condition recurring (happening again) is less than 1% for both procedures.

No. Until researchers find a specific cause of pectus excavatum, you can’t prevent it.

Symptoms — both physical and psychological — are a part of daily life for people with untreated pectus excavatum. People who tell you this condition is purely cosmetic aren’t acknowledging what you feel. Find a provider who will take your symptoms seriously and help you manage them.

Regular checkups with a provider can help them decide when you should have an operation (or if your case is severe enough to need it). After surgery, you’ll need to see your surgeon on a regular basis until you’ve completely recovered.

Questions you can ask your healthcare provider about pectus excavatum may include:

You may develop more symptoms over time. This is likely due to the normal aging process. It also gets harder to make up for pectus excavatum limiting your heart and lungs’ function.

There’s no evidence that pectus excavatum limits life expectancy or causes progressive damage to your heart and lungs over time. But without surgery, your symptoms may get worse.

People with pectus excavatum can carry a normal pregnancy to term.

Yes. Surgeons have done combined heart surgery cases with pectus excavatum repair with excellent outcomes. This requires coordination between the surgeons performing both procedures.

Pectus excavatum — an abnormally developed breastbone — can be a frustrating condition because of its physical and emotional symptoms. Be your own advocate and get the help you deserve for your symptoms. Don’t be embarrassed to talk with healthcare providers about your condition. They’re there to help you like they’ve done for others before you. If surgery is the right option for you, ask questions so you understand the best surgical approach for your situation.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

As your child grows, you need healthcare providers by your side to guide you through each step. Cleveland Clinic Children’s is there with care you can trust.