A scar runs horizontally across Kevin Beason’s chest, from his left armpit to his right.

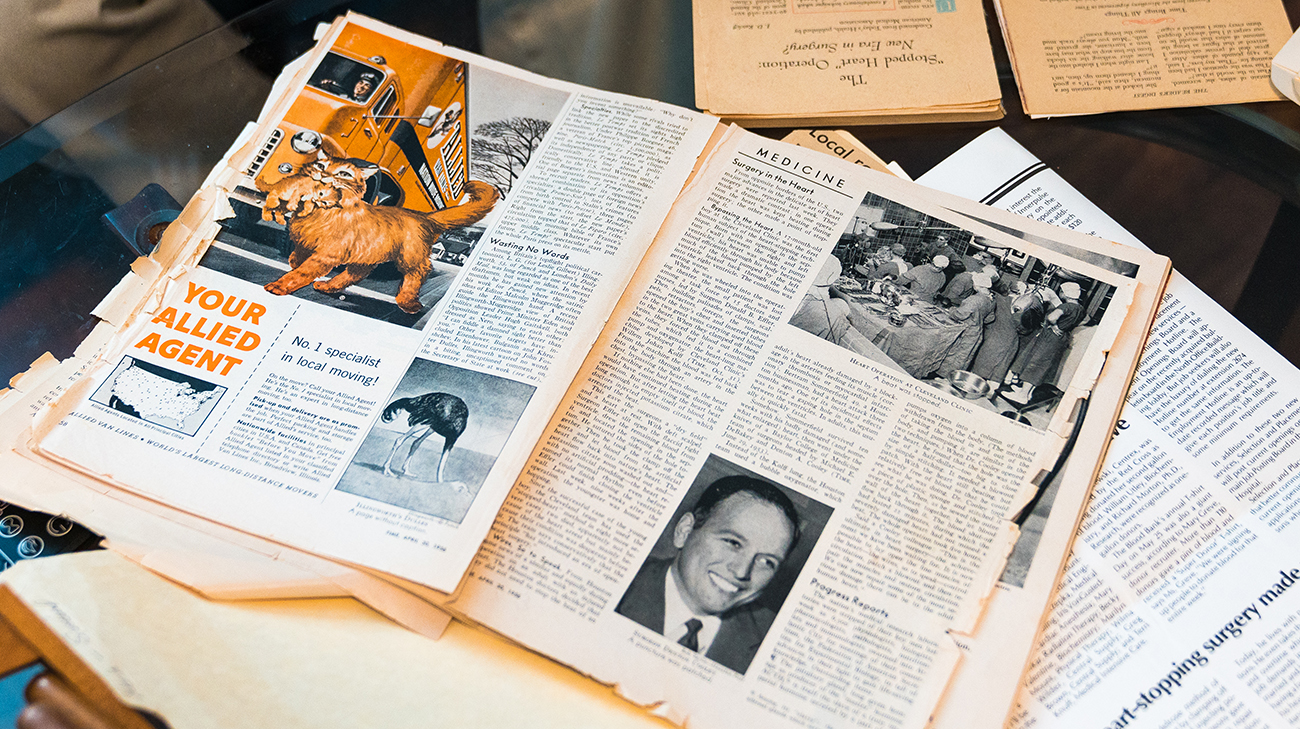

And for the last 65 years, that scar and several age-worn photos and articles clipped from Time and Reader’s Digest magazines have been the only evidence that Kevin once had a serious heart defect as a child.

Major media outlets like Time and Reader's Digest featured Kevin's story in 1956. (Courtesy: Cleveland Clinic)

“In all these years, I’ve never had any problems with my heart,” says the 66-year-old Jacksonville, Florida, grandfather and retired trumpeter. “But at the time, I probably wouldn’t have lived without this experimental surgery.”

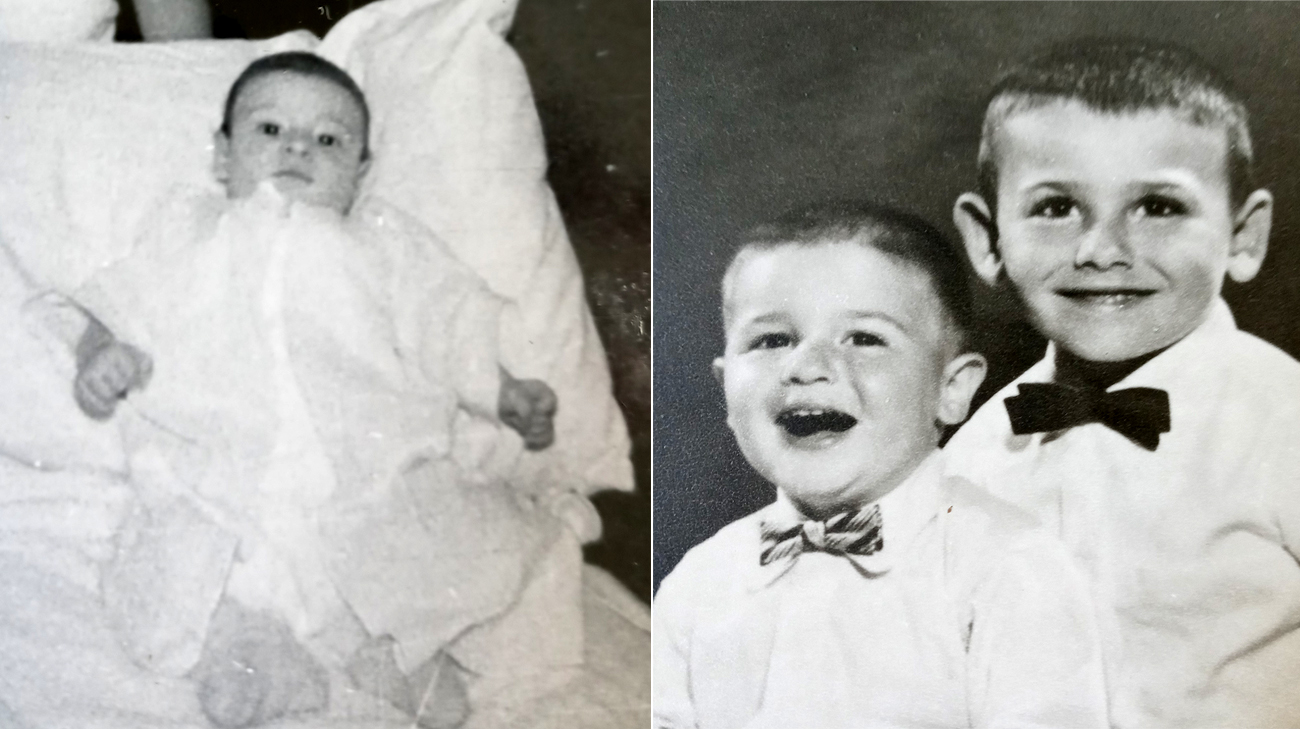

When he was 17 months old, Kevin was debilitated by a hole in his heart called a ventricular septal defect. Weighing just 17 pounds, he became the first patient in the world to undergo a stopped-heart operation.

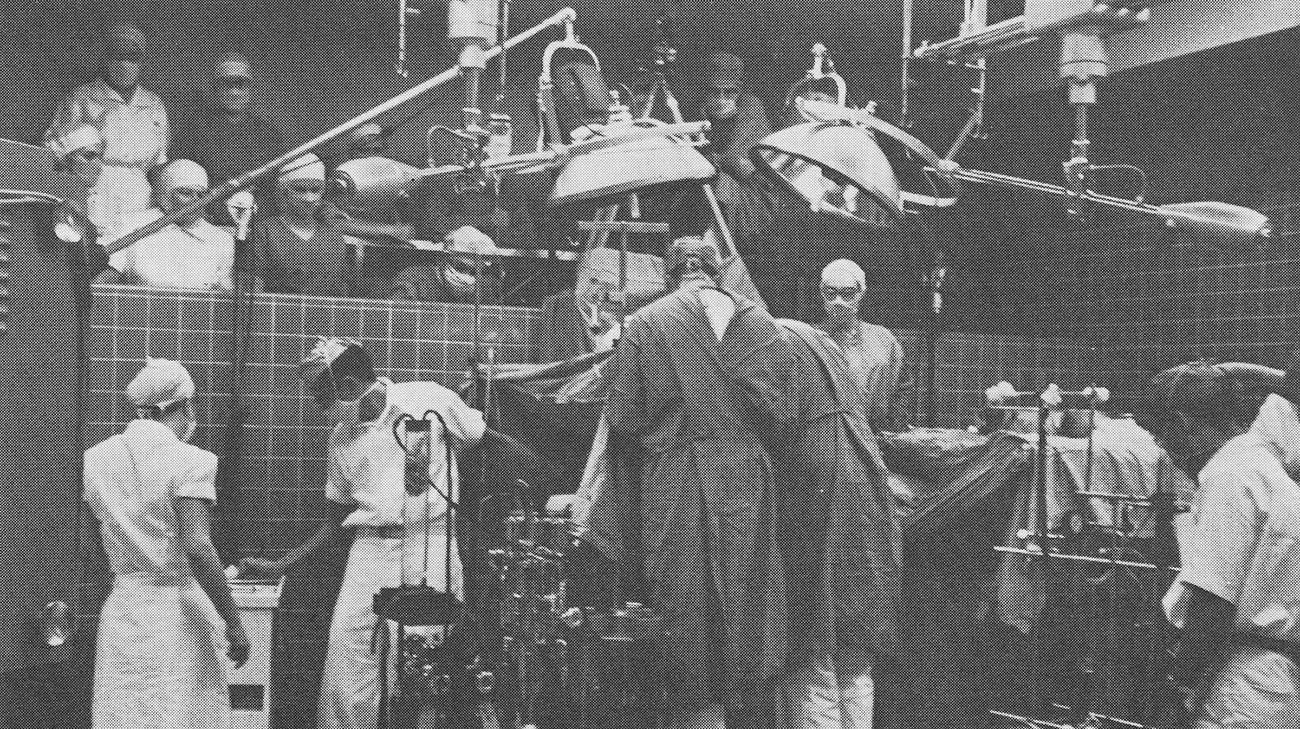

A team of 15 Cleveland Clinic clinicians performed the first stopped-heart operation on February 17, 1956. (Courtesy: Cleveland Clinic)

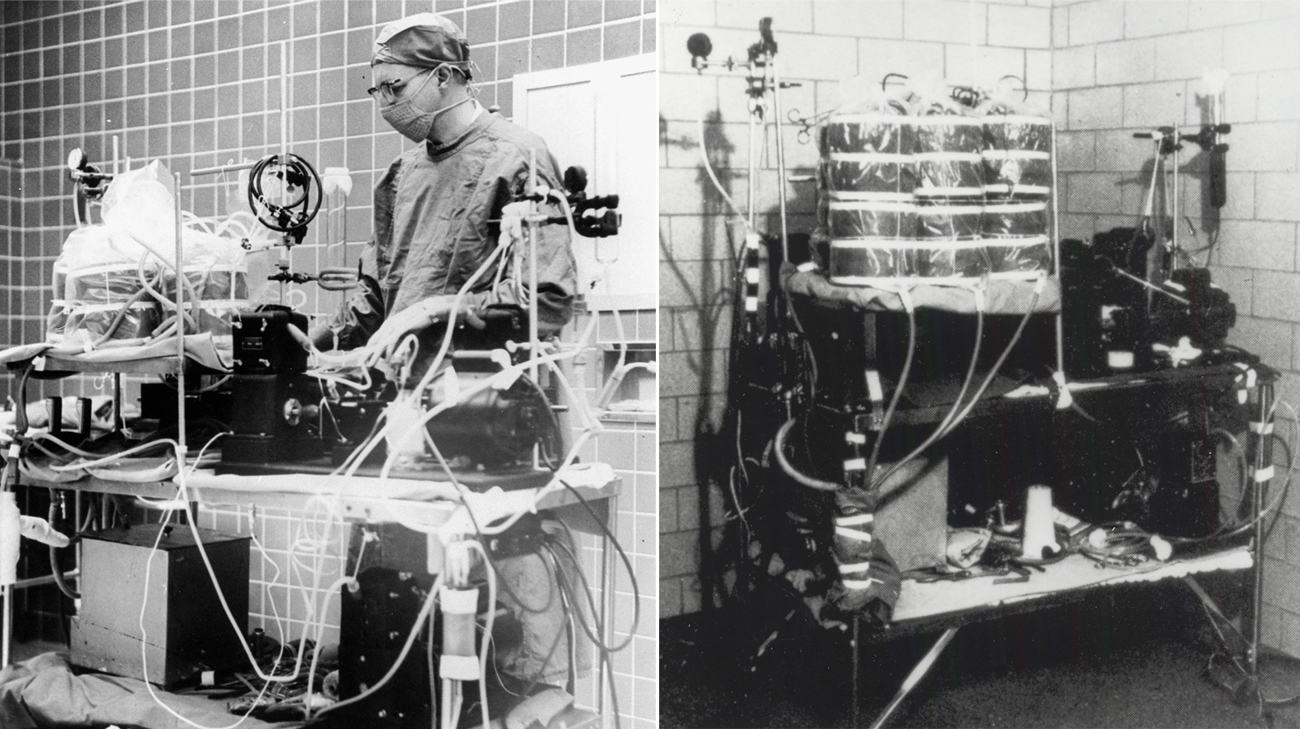

The groundbreaking surgery was performed by a large Cleveland Clinic surgical team on February 17, 1956, led by Donald Effler, MD, and Lawrence Groves, MD. They used a heart-lung machine developed by their colleague, Willem Kolff, MD. The device oxygenated and pumped the body’s blood, keeping Kevin alive while his heart was temporarily stopped for the duration of the open-heart operation.

Today, this type of surgery is commonplace. At the time of Kevin’s surgery, however, the procedure was somewhat controversial, as many inside and outside the medical community were skeptical it would work. But it was successful, bringing the attention of the world to Cleveland Clinic’s pioneering doctors and patient.

“What Dr. Effler and Dr. Groves pioneered with stopping the heart for surgery was a very important milestone,” states Lars Svensson, MD, an internationally renowned surgeon and chairman of the Heart, Vascular & Thoracic Institute at Cleveland Clinic. “Every day, surgeons around the world stop the heart for most types of heart surgery using a similar process as our pioneering doctors did in 1956.”

A heart-lung machine, developed by Willem Kolff, MD, kept Kevin alive during the operation. (Courtesy: Cleveland State University)

Once Kevin’s operation was completed, the change in his health was immediate. He recalls his mother telling him later that his heart quickly returned to normal, and that his recovery was so dramatic “that the nurses would come by my (hospital) room just to watch me grow. By the time I was 3, my height and weight were at normal levels.”

Every year until he was 14, and more frequently when he was very young, Kevin would make the journey from his home near Indianapolis to Cleveland to be examined by cardiologist F. Mason Sones, MD, who helped plan Kevin’s operation and would use his own pioneering procedure – coronary angiogram – to monitor the recovery and performance of Kevin’s heart.

Kevin keenly remembers those examinations in the basement of a Cleveland Clinic building – most likely, Dr. Sones’ B-10 Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory. He recalls that Dr. Sones was always very worried about the ability of Kevin’s lungs to function properly since parts of two ribs were removed for his surgery.

“I was told, repeatedly, not to participate in organized sports. So no basketball, no football, no baseball,” says Kevin. “Because of that, I got really interested in music instead.”

Kevin was born with a heart defect called ventricular septal defects. (Courtesy: Kevin Beason)

So interested, in fact, that Kevin became an accomplished trumpeter. By the time he was a junior in high school, Kevin was taking lessons from Delbert Dale, an internationally acclaimed Indianapolis-based trumpeter who happened to be friends with noted jazz trumpeter Doc Severinsen, who for years led the band for “The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson.”

“Imagine being a kid in a trumpet lesson and have Doc walk in,” says Kevin, who also met with Severinsen when the band leader performed with the Ball State University marching band while Kevin was a student there. “He gave me some tips, too.”

Talented and inspired by his brush with musical greatness, Kevin pursued a music career. Whether touring with off-Broadway shows, appearing with big bands and symphonies, recording commercial jingles or performing as a session musician at renowned studios in Nashville and Muscle Shoals, Alabama, Kevin spent decades as a musician – and certified jeweler.

Kevin became an accomplished trumpet player and often performed with acclaimed musicians. (Courtesy: Cleveland Clinic)

“When I lived in Huntsville, Alabama, I’d work at the jewelry store until 6, drive the two hours to Nashville, eat dinner, work a gig for two hours, and then drive home,” recalls Kevin, who only plays music for fun these days. “I’d be up the next morning to get the kids ready for school.”

While he never met Dr. Effler in person, he recalls getting a letter from the surgeon after an article on the groundbreaking surgery was published in the early 1980s. “He told me that he thought 17 must be my lucky number,” says Kevin. “Besides my age and weight, he said the operation took place on February 17 and they kept me on the heart-lung machine for 17 minutes.”

Dr. Svensson adds, “Even today, closing a hole in the heart in 17 minutes is remarkable. The stopped-heart operation reflects innovation and commitment to great quality of care exhibited by our colleagues in 1956, a dedication we continue to emulate today.

Related Institutes: Heart, Vascular & Thoracic Institute (Miller Family)