Deborah (Debbie) Gump was teaching psychology to her students at Lewis County High School in her hometown of Weston, West Virginia, when she received the phone call she’d been waiting for. Her 20-year-old son Dylan was approved to be a live organ donor. He’d be giving a portion of his healthy liver to his mom, whose liver was damaged from Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis (PSC).

“Everyone knew I only answered the phone during class if it was a call from Cleveland Clinic. I hung up, and told them I’d be having my transplant, then started crying. The whole class cried with me, as they’d all seen me getting sicker and sicker,” says Debbie.

No stranger to health issues, Debbie was diagnosed with ulcerative colitis in 1999 and PSC in 2006 when blood work showed her liver enzymes were elevated. In 2012, she was diagnosed and successfully treated at Cleveland Clinic for Stage 3 colon cancer.

“PSC is a chronic, progressive liver disease resulting from inflammation and scarring of the bile ducts that eventually leads to liver failure. When bile cannot flow normally, it builds up and can lead to itching, jaundice and fatigue. If the liver is damaged too much, cirrhosis can occur, and a transplant may be considered,” says Koji Hashimoto, MD, transplant surgeon and Director of Cleveland Clinic’s Living Liver Donor Transplant Program.

Since she already had established relationships at Cleveland Clinic, Debbie chose to receive monitoring and care for her PSC there as well. For several years, her liver-related health issues were medically managed to a minimum, but about four years ago, she started to appear jaundiced (her eyes and skin developed a yellowish tint).

In 2017, she underwent a transplant evaluation with hepatologist K.V. Narayanan Menon, MD, Medical Director of Liver Transplantation at Cleveland Clinic. Following three days of testing, Debbie was placed on the transplant waiting list.

“In early 2018, I was feeling fine. I worked every day and went to the gym to work out. But by early February, it started to get bad. Doctors suggested I might want to start looking for a live donor,” says Debbie.

According to Dr. Hashimoto, the best benefit of a living donor liver transplant is the patient can receive a liver transplant before they become too ill. Approximately 15-to-20 percent of patients awaiting a liver transplant die or become too sick to receive a transplant.

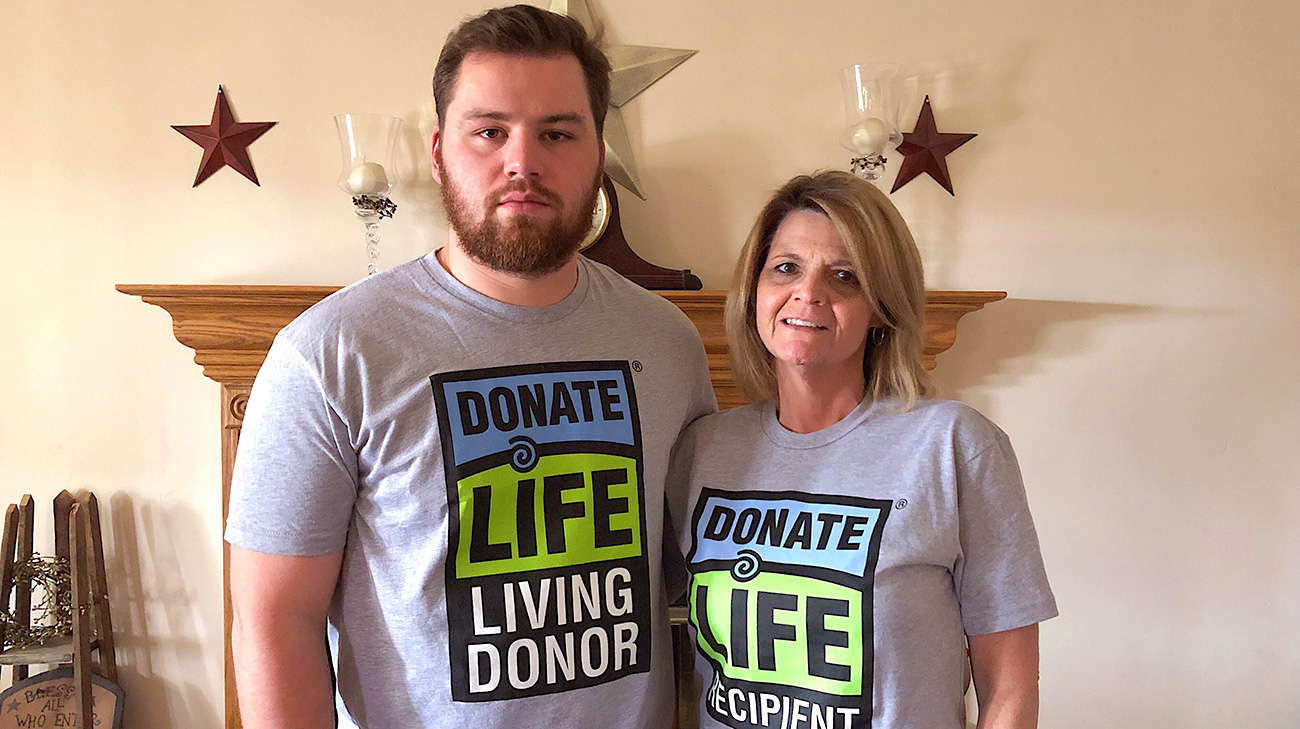

Dylan immediately volunteered to be tested. “My mom didn’t ask me, I just said I’d do it. Anybody would do anything for their mom. I felt lucky that I had a chance to help her,” says Dylan.

A college sophomore at the time, Dylan’s three days of testing was scheduled around his coursework. When he was in Cleveland, he met with many representatives of the transplant team, who told him what would be involved, including the risks. But to Dylan, given the chance to save his mother’s life, any risk was worth it.

The family began waiting for the all-important phone call in February 2018. In April, Debbie developed a severe infection and was admitted to the ICU at her local hospital. About the same time, Dylan was back in Cleveland for the final stage of testing to be a donor — a liver biopsy.

“We literally found out just a couple of weeks before the transplant was scheduled that Dylan was approved to be my living donor,” says Debbie. “Being a mom, I asked if we could put off the surgeries until Dylan finished his college term.”

The short wait time and ability to schedule the surgeries for both the donor and recipient at a convenient time are additional benefits of living donor liver transplants. Debbie’s surgery was scheduled for Monday, May 7, and mother and son were admitted the day before.

“I wasn’t scared. I had met the team and the surgeon and trusted them. I knew I was in good hands,” says Dylan.

Dylan’s surgery with Cleveland Clinic liver transplant surgeon Cristiano Quintini, MD, began about an hour before his mom’s surgery with Dr. Hashimoto.

“My surgery was shorter, so I was in recovery hours before my mom,” says Dylan. “I don’t remember much, but I do remember them taking me in a wheelchair to see her.”

Debbie’s surgery, though lengthy at over 12 hours, was shorter than the family had expected.

“Everything just fell into place. Going into the transplant surgery, I just had the sense that everything was going to be OK. We have extreme faith, and our whole community was praying for us — one of the perks of living in a small town,” says Debbie.

Dylan was out of the hospital five days after surgery and Debbie returned to her West Virginia home 22 days after her transplant. Once there, she followed a care protocol that included frequent blood work and prescribed medications.

By August, Dylan was back to playing collegiate baseball at West Virginia Wesleyan College and Debbie was back in her classroom at Lewis County High School.

“Being a mom, you kind of hope your child won’t have to be the donor, but Dylan was very determined,” says Debbie.

And Dylan? He found the entire experience to be an amazing process. He’s experienced no after affects from the surgery and says he’d 100 percent do it all over again. “Other people think it was such a big thing, but I don’t think it was. To me, it was just the thing to do to save my mom’s life,” he says.

Related Institutes: Digestive Disease & Surgery Institute