Necrotizing fasciitis, also known as flesh-eating disease, is a bacterial infection that affects the tissue under your skin called the fascia. It spreads quickly and can cause life-threatening complications. It requires immediate treatment with surgery and antibiotics.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

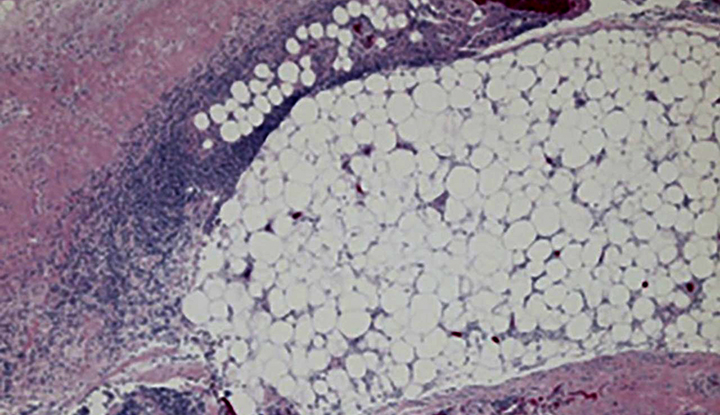

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/Images/org/health/articles/23103-necrotizing-fasciitis)

Necrotizing fasciitis is a severe bacterial infection in the tissue under your skin, the fascia. It spreads rapidly and can cause death.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Necrotizing fasciitis is a form of necrotizing soft tissue infection (NSTI). Some people call necrotizing fasciitis or any NSTI the “flesh-eating disease.” Necrotizing fasciitis is rare. It affects about 1 in every 250,000 people in the United States.

You may see symptoms of necrotizing fasciitis within 24 hours of getting scratched or bitten or cutting yourself. It gets worse quickly. Keep an eye out for areas that look swollen or discolored and grow larger.

This infection needs immediate medical treatment.

There are two types of necrotizing fasciitis:

Early symptoms of necrotizing fasciitis resemble those of the flu. They typically start within 24 hours of a minor injury and include:

Within hours to days, you develop symptoms like:

Advertisement

Get medical care as soon as possible if you have these symptoms.

Bacteria that spread in the tissue under your skin (fascia) cause necrotizing fasciitis. Group A strep bacteria are the most common cause. But you can get it from many different types of bacteria, including bacteria that live in water.

Ways that bacteria can enter your fascia include:

Anybody can get this infection. But you’re at increased risk for it if you have a weakened immune system or diabetes.

Upon infection, the bacteria or bacterium spreads through your fascia. They produce toxins that limit blood flow to your fascia and the tissues around it. This leads to tissue death (necrosis). The toxins can also damage other parts of your body, like your organs.

Due to a lack of blood supply to the tissues, your body’s immune system can’t fight the infection. Antibiotics alone can’t fight it either. You need surgery to stop the spread of the infection and to remove dead tissue.

Necrotizing fasciitis rarely spreads from one person to another. But rarely, in cases of severe infection, your provider might recommend that your close contacts take preventive antibiotics.

You can’t always prevent necrotizing fasciitis. But to reduce your risk of it, do the following:

Many complications of necrotizing fasciitis are serious. They may include:

If your healthcare provider thinks you have flesh-eating disease, they may do diagnostic tests, like:

Your provider may also send a tissue sample to a lab to find the bacteria that’s causing the infection.

You need immediate treatment for necrotizing fasciitis. You’ll receive care in the intensive care unit (ICU) of a hospital.

Surgery is a must for this infection. It’s necessary to remove dead tissue (debridement) and stop the spread of the infection. You may need multiple surgeries.

Your provider will also likely prescribe antibiotics and IV fluids. After surgery, you may need skin grafts or plastic surgery to help the wounds close completely.

Advertisement

You’ll likely need follow-up care to make sure you’re healing well. Ask your healthcare provider what typical healing looks like. Ask about signs to look for that may mean something is wrong.

Your prognosis (outlook) for necrotizing fasciitis depends on many factors, like:

The odds of survival are best for people who get immediate debridement surgery, IV fluids and broad-spectrum antibiotics. Even with treatment, about 1 out of 3 people die from this condition.

After initial treatment, it may take a while to feel healthy again. Necrotizing fasciitis can drastically change your body. You may benefit from physical therapy and other types of rehabilitation. It’s also important to get mental health help if the aftermath of necrotizing fasciitis is causing distress.

Recovering from necrotizing fasciitis can be a challenging journey, both physically and emotionally. It may greatly change your daily life. Remember that healing takes time. And you don’t have to go about it alone. Seek help and support from your healthcare team and loved ones.

Advertisement

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Have a virus, fungus or bacteria? Some of these “bugs” won’t go away on their own. Cleveland Clinic’s infectious disease experts are here to help.