Tuberous sclerosis is a rare genetic disorder that causes cells in parts of your body to reproduce too quickly. The excess cells form noncancerous tumors, which can form anywhere in your body. The severity of this condition often depends on tumor locations. Mild or moderate cases are often manageable with medication or other treatments.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) is a rare genetic disease that causes noncancerous tumors to grow throughout your body. This condition, sometimes known simply as tuberous sclerosis, can affect people in many ways. People with less severe cases may see very few effects and have a normal lifespan. Severe cases can lead to serious complications.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

TSC is a disease that may progress slowly. Some symptoms may begin early in life, but it may take years for others to appear. People with this condition will need to see a healthcare provider regularly throughout their life to monitor this condition.

TSC is a condition you have when you’re born. Healthcare providers diagnose half of all cases by the time a child reaches 7 months old. However, milder cases may go unnoticed for years. People diagnosed with TSC as children can also have other symptoms diagnosed after they become adults. This condition is equally likely to happen in everyone, with no differences due to sex, race or ethnicity.

TSC is rare. There are about 50,000 people who have it in the U.S., and about 1 million have it worldwide.

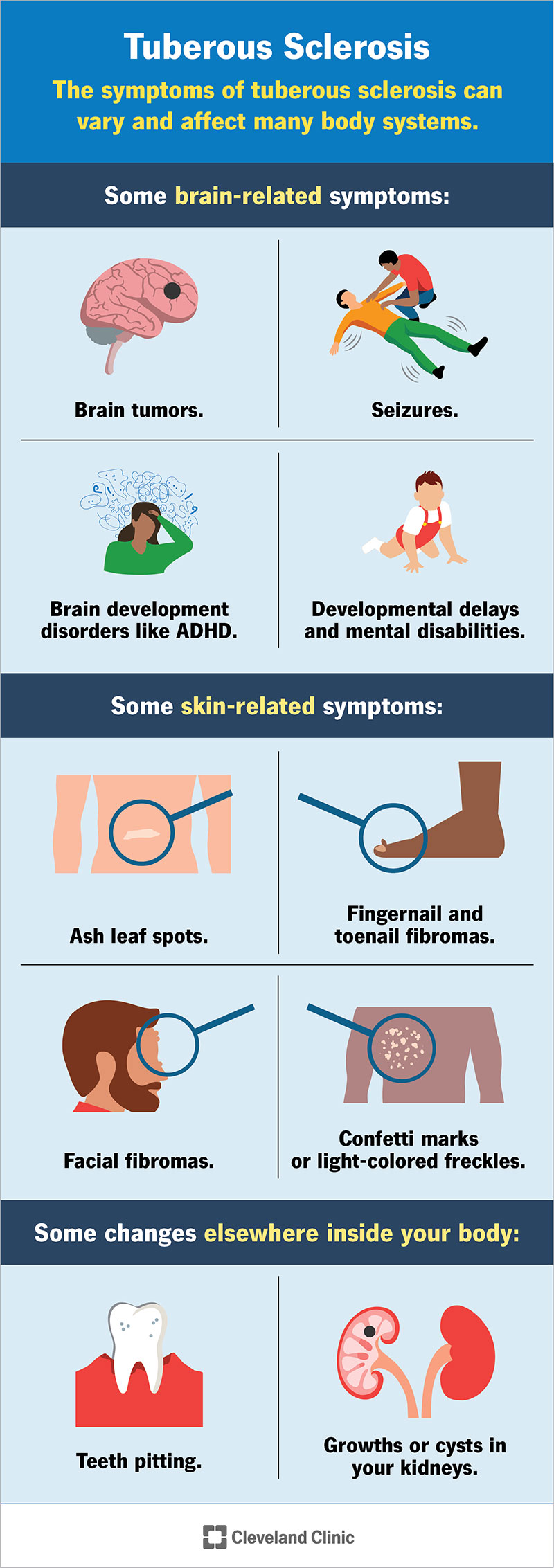

The main effect of TSC is that it causes clusters of cells to grow and become tumors. The most common place for this to happen is your brain. TSC can also cause changes in your skin, especially when you’re very young. Those skin changes are often the first symptom or sign that a person has this condition.

TSC can affect your heart and kidneys, too. Different kinds of growths are common in these organs. Growths in other locations are less common.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/17586-tuberous-sclerosis)

The symptoms of tuberous sclerosis can vary greatly depending on the organs or body parts affected. Symptoms tend to fall under the following categories:

Advertisement

Brain-related symptoms happen when TSC causes tumors or cortical tubers (hamartomas) to grow in your brain. These tumors aren't cancerous but can still damage or disrupt your brain function. Examples of these kinds of tubers and tumors include:

In many cases, TSC causes additional conditions, which can involve other symptoms.

While seizures and mental disabilities are common with TSC, not everyone with this condition will have them. It’s also possible to have TSC with seizures but without mental disabilities.

Skin-related symptoms are often the earliest indicator that you have TSC. Experts estimate that 90% of people with TSC have one or more of the following:

Advertisement

The growths that happen with TSC, either tumors or cysts, can happen in many other places throughout your body. Some other changes can happen, too. The possible changes include:

TSC is a genetic disease, meaning it happens because of DNA mutations. Most cells in your body reproduce and create their replacements. Your body controls this process using tumor-suppressing proteins.

Advertisement

Those proteins control how fast cells reproduce and cell size. Without the right balance between these proteins, you’d have a surplus of oversized cells. And with nowhere to go, those cells will push beyond where they should be and form tumors.

The mutations that cause TSC can happen in two ways:

Experts divide the signs and symptoms into two categories: major and minor features. A confirmed diagnosis of TSC requires two or more major features. Because symptoms may appear over time, a healthcare provider can classify your diagnosis as “possible TSC” if you have only one major feature or at least two minor features.

Advertisement

Because TSC can cause so many different symptoms and effects, there are many possible tests. The tests often vary depending on your symptoms. Because so many factors can affect the tests you’ll undergo, your healthcare provider is the best person to tell you what tests they recommend and why. Some common tests for tuberous sclerosis are listed below. Genetic testing ultimately confirms the diagnosis of TSC and helps identify the specific mutation in the TSC genes.

Diagnostic imaging and other forms of testing are most likely for brain-related symptoms. This is especially true if you have seizures (or any evidence that suggests you could have seizures). Imaging scans and tests that are possible include:

If a provider suspects an intellectual disability, they might recommend undergoing certain types of cognitive tests. These tests help identify problems with how your brain and thinking processes work. They usually include questions or tasks related to memory, judgment and decision-making.

A physical examination is a key part of identifying TSC. Many of the signs and symptoms of this condition are visible at an early age. A healthcare provider can use certain tests to help them confirm or rule out TSC. The most likely tests include:

Genetic testing is a key tool that can help detect TSC. Between 75% and 95% of cases will have a TSC1 or TSC2 mutation. You can still have it without a detectable mutation, but this is less common.

Many changes with TSC start when a person is still a fetus developing in the uterus. Healthcare providers can sometimes detect those changes during routine prenatal care, especially ultrasound tests, or with CT or MRI scans soon after birth.

Tuberous sclerosis isn’t curable, but it’s often treatable. The treatment approaches usually depend on the types of symptoms. The most common forms of treatment are:

Depending on your symptoms, your healthcare provider may recommend other medications, too. However, these are often very specific to your symptoms, health history, personal needs and preferences, and more.

Different types of medications can help treat symptoms of TSC. There are medications that can slow or stop tumor growth, or even shrink tumors. Other commonly used medications prevent seizures, which are among the most common and most dangerous symptoms of TSC.

The growths that happen with TSC can sometimes cause problems, depending on where they happen. Sometimes, surgery is necessary to remove growths causing issues with various organs or body systems. Your healthcare provider can tell you more about possible surgeries and other treatment options you have.

Many symptoms of TSC are very visible — and you might feel anxious, self-conscious, embarrassed or ashamed. A dermatologist can help reduce or remove and the skin changes that can come with TSC. While these treatments are usually a temporary solution, they can make a big difference in your mental health.

Examples of dermatology treatments for TSC-related skin symptoms include:

The possible side effects or complications of TSC treatments vary widely. This is especially true because there are so many possible symptoms and treatment options. Because of this, your healthcare provider is the best person to tell you the side effects or complications you might experience. They can also tell you more about how long it might take to feel better after treatment.

Most people with TSC will need regular imaging scans every one to two years, especially MRI scans. This usually starts early in childhood and lasts until age 21. Some people will need regular imaging scans throughout their life to detect new tumors or monitor existing ones.

TSC can have a wide range of effects depending on how severe it is.

Tuberous sclerosis is a permanent, lifelong condition.

There’s no way to prevent TSC. Genetic counseling can help you understand the likelihood of your child inheriting this condition and what — if anything — you can do to make that less likely. Experts often recommend this counseling if you have a first-degree relative (a parent or sibling) who has TSC.

If your provider prescribes medication, you should take it as prescribed. You shouldn’t stop taking medications without first talking to your provider. Stopping them suddenly could increase your risk of symptoms returning or getting worse.

Other ways to take care of yourself can vary from person to person. That’s because many factors contribute to what you should do. Your healthcare provider is the best person to offer guidance on what you can and should do to care for yourself and manage your condition.

If you have TSC, you’ll likely need to see a healthcare provider regularly throughout your life. This allows your healthcare provider to monitor the condition and track the changes it causes. Both are key parts of avoiding serious complications from TSC.

Depending on your symptoms and where you have growths or tumors, there are certain symptoms that mean you need immediate medical care. The most common of these is status epilepticus (SE).

SE is when you have a seizure that lasts longer than five minutes or have two or more seizures in a row without time between them to recover. SE is a life-threatening medical emergency. If you’re with someone with seizures that meet either of these definitions, you should immediately call 911 (or your local emergency services number).

Other symptoms that mean you need medical attention can vary. Your healthcare provider is the best person to tell you what symptoms you should watch for, and what you can do if you experience or notice them.

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC), also known as tuberous sclerosis, is a rare genetic condition. This condition causes noncancerous tumors to grow in various places throughout your body, especially in your brain or on your skin. Thanks to advances in modern medicine and imaging technology, it’s often possible to monitor and treat this condition as needed throughout your life. Many people with TSC can live long, healthy lives.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Do certain health conditions seem to run in your family? Are you ready to find out if you’re at risk? Cleveland Clinic’s genetics team can help.