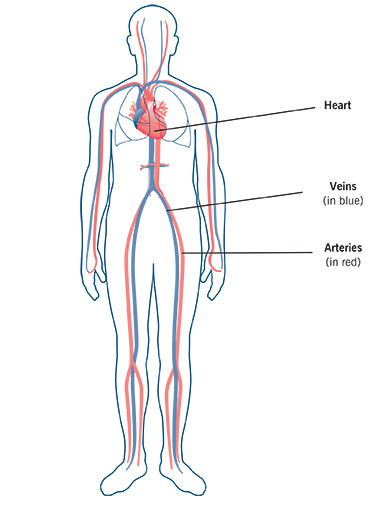

Your heart pumps blood through a network of blood vessels that carry blood through your body. Together, your heart and blood vessels are called the circulatory system. Blood carries oxygen and nutrients to your body’s tissues and carries carbon dioxide and waste products away from the tissues. Your blood never stops flowing through your body. Your heart is the pump that keeps the blood flowing.

How does blood travel through the body?

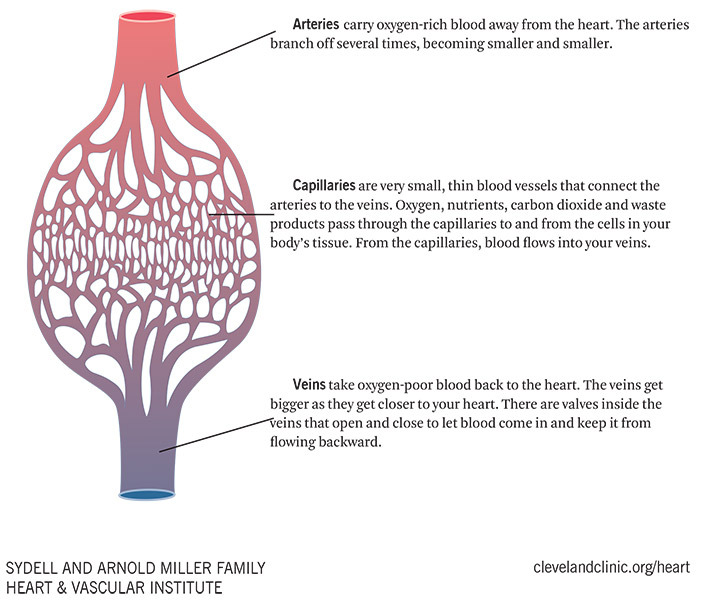

There are three types of blood vessels:

Circulatory System

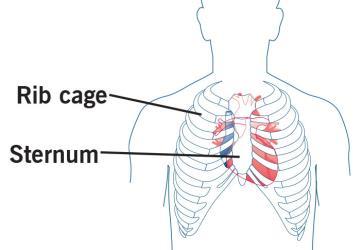

Where is the heart?

The heart is located under the rib cage, to the left of the breast bone (sternum), between the lungs.

Your heart is an amazing organ. Shaped like an upside-down pear, this fist-sized powerhouse pumps five or six quarts of blood each minute to all parts of your body.

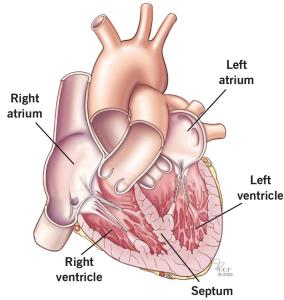

What does a normal heart look like?

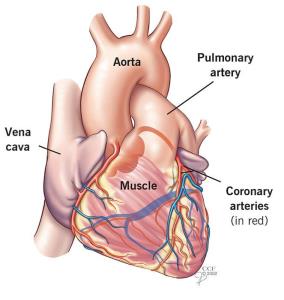

Outside view - The walls of the heart are made of muscle. The walls squeeze (contract) to pump blood into the arteries.

Inside view - The heart has four chambers. The septum is a muscular wall that divides the heart into the right and left sides. Each side has:

- Two atria (top chambers of the heart that receive blood from the veins).

- Two ventricles (bottom chambers of the heart that pump blood into the arteries). The left ventricle is the major pumping chamber of the heart.

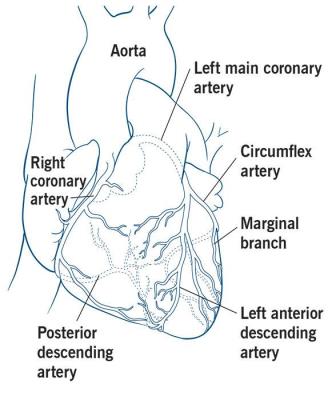

The coronary arteries

The heart gets its own blood supply through the coronary arteries. Two major coronary arteries branch off near the point where the aorta and the left ventricle meet. These arteries and their branches supply blood to all parts of the heart muscle.

The right coronary artery supplies blood to the right atrium, right ventricle, bottom part of the left ventricle and back of the septum.

The left coronary artery divides into two branches:

- Circumflex artery: Supplies blood to the left atrium and the side and back of the left ventricle.

- Left anterior descending artery: Supplies blood to the front and bottom of the left ventricle and front of the septum.

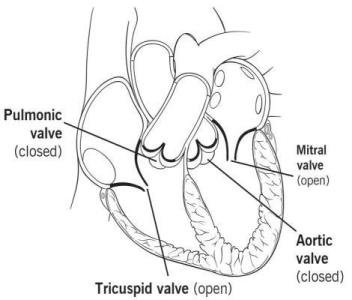

The heart valves

There are four valves in the heart —the pulmonic valve, tricuspid valve, mitral valve and aortic valve.

The heart valves work the same way as one-way valves in the plumbing of your home. They open to let blood through, and close to keep blood from flowing in the wrong direction.

How the heart valves work

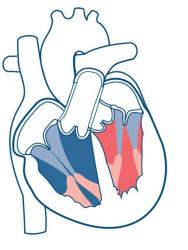

Open tricuspid and mitral valves

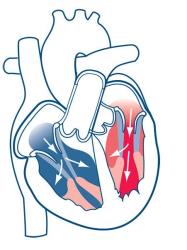

Oxygen-poor blood flows from the body through two large veins — the inferior and superior vena cavae — into the right atrium. Blood flows from the right atrium into the right ventricle through the open tricuspid valve, and from the left atrium into the left ventricle through the open mitral valve.

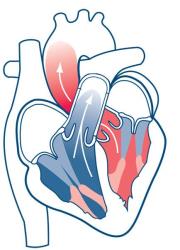

Closed tricuspid and mitral valves

When the right ventricle is full, the tricuspid valve shuts and keeps blood from flowing backward into the right atrium when the right ventricle squeezes (contracts).

When the left ventricle is full, the mitral valve shuts and keeps blood from flowing backward into the left atrium when the left ventricle contracts.

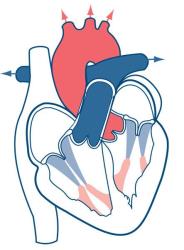

Open pulmonic and aortic valves

As the right ventricle starts to contract, the pulmonic valve is forced open. Blood is pumped out of the right ventricle, through the pulmonic valve and into the pulmonary artery, which carries the blood to the lungs.

As the left ventricle starts to contract, the aortic valve is forced open. Blood is pumped out of the left ventricle through the aortic valve and into the aorta, which branches off into many arteries that carry blood throughout the body.

Closed pulmonic and aortic valves

When the right ventricle finishes contracting and starts to relax, the pulmonic valve snaps shut. This keeps blood from flowing backward into the right ventricle.

When the left ventricle finishes contracting and starts to relax, the aortic valve snaps shut. This keeps blood from flowing backward into the left ventricle.

This whole process happens in a single heartbeat and repeats over and over, keeping blood flowing throughout your body.

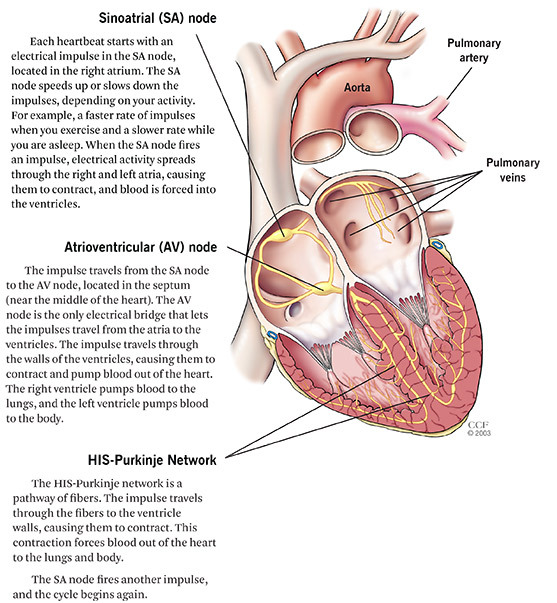

The heart’s electrical system

The heart has an electrical system that controls the timing of the contractions that create your heartbeat. Your heart works best when the electrical impulses are perfectly timed.

How does my doctor check my heart?

Pulse

Your doctor feels your pulse to check your heart’s rate and rhythm. Each pulse matches up with a heartbeat that pumps blood into the arteries. The force of the pulse also helps your doctor check the strength of blood flow to different areas of your body.

Listen to your heart

Your doctor uses a stethoscope to listen to your heart. Your heart valves make noise as they open and close. Your doctor will listen to your heart sounds to check for problems with your valves or heart rate and rhythm.

Check your blood pressure

Blood pressure is the force of blood against your artery walls.

Blood pressure is recorded as two measurements:

- Systolic pressure (the top number): Pressure in the arteries while your heart contracts. This is

the higher of the two numbers included in a blood pressure reading. - Diastolic pressure (the bottom number): Pressure in the arteries while your heart is relaxed between heartbeats. This is the lower of the two numbers included in a blood pressure reading.

Measure your ejection fraction

Ejection fraction (EF) is a test that measures how well your heart pumps with each beat. Your EF is measured as a percentage.

Your EF can go up and down, based on your heart condition and procedures and treatments you’ve had.

Know Your ejection fraction

If you have a heart condition, it is important for you to know your EF. Your EF helps your doctor plan the best treatment for you and know how well your treatment is working.

You should have your EF measured when you are first diagnosed with a heart condition, and as often as your doctor recommends.

- Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) is the measurement of how much blood your left ventricle pumps out with each contraction. In most cases, the term “ejection fraction” refers to LVEF.

- Right ventricular ejection fraction (RVEF) is the measurement of how much blood the right side of your heart pumps out to the lungs, where it collects oxygen.

A normal LVEF ranges from 55% to 70%. An LVEF of 65, for example, means that 65% of the total amount of blood in the left ventricle is pumped out with each heartbeat.

A lower-than-normal/reduced LVEF may be a sign of damage to the heart muscle because of a heart attack, heart muscle disease (cardiomyopathy) or other problem. It can also confirm that a patient has systolic heart failure.

An EF less than 30% increases the risk of life-threatening irregular heartbeats that can cause sudden cardiac arrest and sudden cardiac death. If you have a very low EF, your doctor may talk to you about getting an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD).

Your doctor can measure your EF with:

- Echocardiogram (echo) - an ultrasound of your heart.

- Cardiac catheterization.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of your heart.

- Multiple gated acquisition (MUGA) scan, also called a nuclear stress test.

- Computerized tomography (CT) scan of your heart.