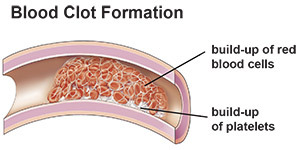

When you have a cut that bleeds, your body forms a blood clot to stop the bleeding. The clot is made from proteins and particles in your blood, called platelets. The process of forming a clot is called coagulation.

Normal coagulation is important and starts the healing process. Abnormal coagulation (the blood clots too much) is called a hypercoagulable state (thrombophilia).

Are hypercoagulable states dangerous?

Hypercoagulable states can be dangerous, especially if you don’t know you have the condition or don’t get treatment. A hypercoagulable state increases your risk of having blood clots in the arteries (blood vessels that carry blood away from the heart) and veins (blood vessels that carry blood to the heart). A clot inside a blood vessel is called a thrombus or an embolus.

Blood clots in your veins or venous system can travel through your bloodstream and cause deep vein thrombosis (a blood clot in the veins of the leg, arm, brain, liver, pelvis, intestines or kidneys) or a pulmonary embolus (blood clot in the lungs).

Blood clots in the arteries increase your risk of stroke, heart attack, severe leg pain, trouble walking and the loss of a limb.

What causes hypercoagulable states?

You may be born with a hypercoagulable state (inherited) or it may be caused by a variety of risk factors (acquired).

Inherited hypercoagulable conditions include:

- Factor V Leiden (the most common).

- Prothrombin gene mutation.

- Low levels of natural proteins that prevent clotting (such as antithrombin, protein C and protein S).

- High levels of homocysteine.

- High levels of fibrinogen or dysfunctional fibrinogen (dysfibrinogenemia).

- High levels of factor VIII and factor IX and XI (rare).

- Hypoplasminogenemia, dysplasminogenemia and high levels of plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI-1).

Risk factors for acquired hypercoagulable conditions include:

- Cancer.

- Some medications used to treat patients with cancer, such as tamoxifen, bevacizumab, thalidomide and lenalidomide.

- Recent trauma or surgery.

- Having a central venous catheter.

- Obesity.

- Pregnancy.

- Estrogen supplements, including birth control pills.

- Hormone replacement therapy.

- Prolonged bed rest or lack of movement.

- Heart attack, congestive heart failure, stroke, pneumonia, inflammatory disease and other conditions that lead to being less active.

- Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (low platelet levels caused by heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin).

- Long trips on a plane.

- Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome.

- Previous deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism.

- Myeloproliferative disorders such as polycythemia vera, essential thrombocytosis or paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria.

- Inflammatory bowel syndrome (IBS).

- HIV/AIDS.

- Nephrotic syndrome (too much protein in the urine).

Having a risk factor does not mean you have a hypercoagulable state.

How do I find out if I have a hypercoagulable state?

Careful Medical History

Your doctor will carefully review your personal and family medical history to help determine your risk of having a hypercoagulable state.

You may be a candidate for a screening if you have:

- A family history of abnormal blood clotting.

- Abnormal blood clotting before Age 50.

- Thrombosis in an unusual place, such as veins in your arm(s), liver, intestines, kidney(s) or brain.

- Blood clots that happen without a known or obvious reason.

- Repeat blood clots.

- A history of several miscarriages.

- Stroke at a young age.

Laboratory testing

You may need blood tests to get more information about your condition and check for health problems that can cause you to have abnormal blood clotting.

These tests should be done in a specialized coagulation laboratory. A pathologist or clinician who is an expert in coagulation, vascular medicine or hematology should read the results.

It is best to have the tests when you are not having an acute blood clotting event.

The most common lab tests include:

- PT-INR: The pothrombin time (PT or protime) test to check your International Normalized Ratio (INR). This is a measure of how fast your blood clots and is used when you take warfarin (Coumadin) to see if you need changes to your dose.

- Activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT): Measures the time it takes blood to clot. This test is also used to make sure your blood is not too thin or thick.

- Fibrinogen level: Fibrinogen is a blood plasma protein that helps your blood clot.

- Complete blood count (CBC): This test measures the number and types of cells in your blood.

You may need one or more tests to help find out if your condition is genetic. These may include:

- Genetic tests, including factor V Leiden (Activated protein C resistance) and prothrombin gene mutation (G20210A) (the most common types of genetic defects that cause abnormal blood clotting).

- Antithrombin activity.

- Protein C activity.

- Protein S activity.

- Fasting plasma homocysteine levels.

Your doctor may order other tests and will talk to you about these before you have them done. Testing may also be recommended for relatives who could be at risk for clotting problems.

Common tests used to find out if your condition is acquired include:

- Anticardiolipin antibodies (ACA) or beta-2 glycoproteins, which are part of antiphospholipid antibody syndrome.

- Lupus anticoagulants (LA), which are part of antiphospholipid antibody syndrome.

- Heparin antibodies.

The test results will help your doctor know your risk of clotting problems in the future and help create your plan of care.

What treatments are available for patients with a hypercoagulable state?

Treatment is usually needed only if you have a blood clot in a vein or artery. Anticoagulant medications ("blood thinners") make it harder for blood to clot and prevent more clots from forming.

These medications include:

- Warfarin (Coumadin) comes in tablet form and is taken by mouth. This medication is used for long-term treatment.

- Heparin is a liquid medication given in the hospital through an IV or by injection under the skin (subcutaneous)

- Low-molecular-weight heparin is given by subcutaneous injection once or twice a day; it can be taken at home. This medication is not okay to use if you have serious kidney disease.

- Fondaparinux (Arixtra) is given by subcutaneous injection; it can be taken at home.

- Direct oral anticoagulants, such as dabigatran (Pradaxa), rivaroxaban (Xarelto), apixaban (Eliquis) and edoxaban (Savaysa). These medications do not require routine blood tests or food restrictions and have fewer interactions. Most of these drugs are not okay to take if you have serious kidney disease.

Your doctor will talk to you about the benefits and risks of these medications, explain which one is best for you, and give you details about taking the medication (how much, how often, if you need blood tests or need to make changes to your diet, etc).

Please talk to your doctor about any questions or concerns you have about your medication or condition.

If you are taking warfarin (Coumadin):

- You will need frequent blood tests (PT/INR). The tests are done to check how well the medication is working. It is very important to keep all lab appointments so your doctor knows how you are responding to the medication and can make any needed changes to your treatment.

- You should order and wear a medical ID bracelet so you can get the right medical care in case of an emergency. Keep this bracelet/ID with you at all times.

- You may bleed or bruise more easily when you get hurt. Call your doctor if you have heavy or unusual bleeding or bruising.

- Some nonprescription (over-the-counter) medications (especially NSAIDs, such as aspirin and ibuprofen) affect how anticoagulants work. Do not take any other medications or supplements unless you talk to your doctor about them.

- Ask your doctor about changes to your diet when taking warfarin. Certain foods, such as foods high in vitamin K (found in brussel sprouts, spinach and broccoli) can change the way the medication works.

- You should not take warfarin (Coumadin) if you are pregnant or plan to become pregnant. If you are, ask your doctor about switching to a different type of anticoagulant medication.