What is an atrial septal defect (ASD)?

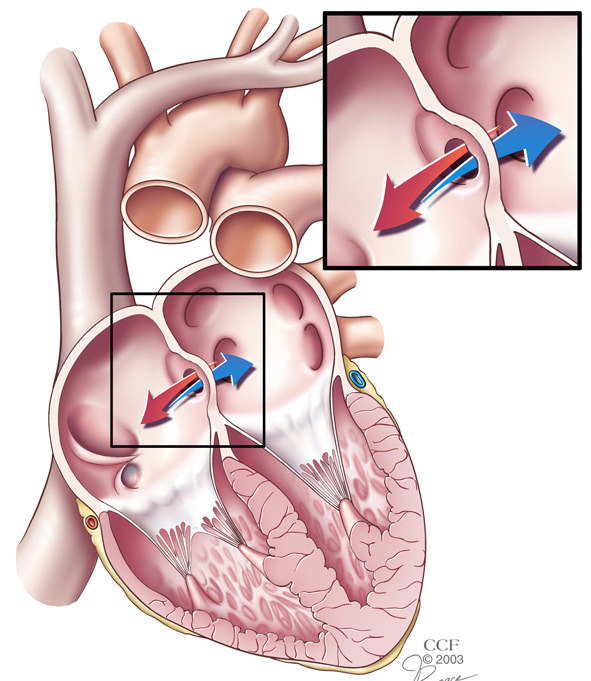

An atrial septal defect (ASD) is a hole in the septum, which is the muscular wall that separates the heart’s two upper chambers (atria). An ASD is a defect you are born with (congenital defect) that happens when the septum does not form properly. It is commonly called a “hole in the heart.”

A secundum ASD is a hole in the middle of the septum. The hole lets blood flow from one side of the atria to the other. The direction depends on how much pressure is in the atria.

More complicated and rare types of ASDs involve different parts of the septum and abnormal blood return from the lungs (sinus venosus) or heart valve defects (primum ASDs).

What causes ASDs?

Most congenital heart defects are likely caused by a combination of genetics and factors involving the mother while she is pregnant, such as use of alcohol and street drugs, as well as diseases such as diabetes, lupus and rubella. About 10 percent of congenital heart problems are caused by specific genetic defects.

How common are ASDs?

Atrial septal defects are the third most common type of congenital heart defect, and among adults, they are the most common. The condition is more common in women than in men.

What are the long-term effects of ASDs?

Normally, the right side of the heart pumps blood that is low in oxygen to the lungs, while the heart’s left side pumps oxygen-rich blood to the body. When you have an ASD, blood from the left and right sides mix, and can keep your heart from working as well as it should.

If your ASD is larger than 2 cm, you have a greater risk of problems such as:

- Right heart enlargement, which leads to heart failure.

- Abnormal heart rhythms, including atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter, affect 50 to 60 percent of all patients over 40 with an ASD.

- Stroke.

- Pulmonary hypertension (high blood pressure in the arteries that supply blood to the lungs). Blood normally flows from the left side of the heart to the right, but having an ASD and severe pulmonary hypertension can cause the blood flow to be reversed. When this happens, oxygen levels in the blood drop, which leads to a condition called Eisenmenger syndrome.

- Leaking tricuspid and mitral valves caused by an enlarged heart.

What are the symptoms of an ASD?

Many people have no idea they have an ASD because they do not have symptoms. Some patients find out about the defect when a chest X-ray for another problem shows that the right side of the heart is bigger than normal.

By age 50, an ASD can cause symptoms like shortness of breath, fainting, irregular heart rhythms or fatigue after mild activity or exercise.

How is an ASD diagnosed?

Tests to check for an ASD include:

- Electrocardiogram (ECG/EKG) – a graph of the heart’s electrical activity (heartbeat).

- Chest X-ray – to check the size of the heart and the blood vessels that supply blood to the lungs.

- Transthoracic echocardiography/Doppler examination – an ultrasound image of the heart combined with measurements of blood flow to check the heart’s structure and see how well it is working.

- Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) Doppler examination – an ultrasound taken through the esophagus is used to get a better picture of the atria and more details about the size and shape of the ASD. A TEE helps the doctor can also be used to check the heart valves.

- Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) Doppler examination – an ultrasound taken through the esophagus is used to get a better picture of the atria and more details about the size and shape of the ASD. A TEE helps the doctor can also be used to check the heart valves.

- Intracardiac echocardiography (ICE)/Doppler examination – an ultrasound taken inside the heart. A tiny camera (echo probe) is sent to the heart through a peripheral vein. The test shows the size and shape of the defect and the direction of the blood flow across it. This study is often used during percutaneous (nonsurgical) repair of the defect.

- Right heart catheterization – a small, thin tube (catheter) is inserted into the heart through a peripheral vein. Pressures and the amount of oxygen in the blood (oxygen saturations) are measured in each chamber of the heart. The oxygen levels determine how much blood is flowing across the ASD. Your doctor may also use a tiny balloon at the end of the catheter or a special dye to check the size of the defect (atrial angiogram).

- Left heart catheterization – during this procedure, a special dye is sent into the blood vessels of the heart through a catheter (angiography). The test can check for coronary artery disease (hard, narrow arteries).

What are my treatment options?

Treatment for patients with an ASD depends on the type and size of the defect, its effect on the heart, and other health conditions you have, such as pulmonary hypertension, valve disease or coronary artery disease.

In general, treatment is recommended if you have symptoms and/or a large ASD that causes significant shunting (flow of blood through the defect) and the right side of your heart is bigger than normal.

The bigger the defect is, the more shunting you have. And, the more shunting you have, the bigger your risk of problems like atrial fibrillation and pulmonary hypertension. Also, the amount of shunting you have usually relates to how enlarged the right side of your heart is.

The amount of shunting is measured using echocardiography, MRI or catheterization (see above).

ASD repair

Nonsurgical treatment

Nonsurgical (percutaneous) repair is the preferred treatment for most patients with secundum ASDs. But, depending on the size, shape and type of ASD you have, you may need surgery. Your doctor will let you know which type of repair is best for you.

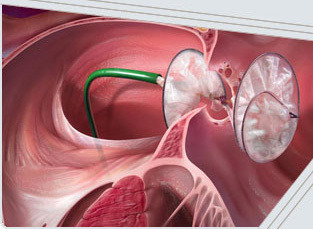

This type of repair uses a device to close the hole in the septum.

Two different brands of closure devices are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for percutaneous ASD closure — the Amplatzer® Septal Occluder and the GORE HELEX® Septal Occluder.

The designs of the devices are different, but they work in similar ways.

The device is put in place using a long, thin tube called a catheter. The device is attached to the catheter, which is guided to your heart through a vein in your groin. When the device is released from the catheter, it opens up and seals the hole. Over time, tissue grows over the implant and it becomes part of the heart.

If your doctor recommends this type of repair, you will have a cardiac catheterization to check the size and location of the defect and measure pressures in your heart.

After the procedure, you will need to take a blood-thinning medication to keep clots from forming on the device. Your doctor will talk to you about the right type of medication for you and how long you need to take it.

(Photo used with permission from AGA Medical Corporation)

Percutaneous closure devices for ASD repair

AMPLATZER® Septal Occluder

The AMPLATZER® Septal Occluder has two Nitinol wire mesh discs filled with polyester fabric. The device is put in place with a catheter and slowly released until the discs of the device sit on each side of the defect, like a sandwich. The two discs are linked together by a short connector, and all are filled with polyester fabric to help the device close.

(Photo used with permission from W.L. Gore & Associates, Inc.)

GORE HELEX® Septal Occluder

The GORE HELEX® Septal Occluder is a disc-like device that consists of ePTFE patch material supported by a single Nitinol wire frame. The device is put in place with a catheter and slowly pushed out until it covers the defect. The device bridges the septal defect.

Surgical repair

Surgical repair usually involves using a tissue patch to close the ASD. The tissue often comes from your own pericardium (membrane around the heart). Some secundum ASDs can be surgically closed with sutures alone. Your doctor may be able to perform the surgery using a small incision or robotic procedure.

Follow-up care

Follow-up visits

Your doctor will let you know how often you need to be seen for follow-up visits. A typical schedule is 3, 6 and 12 months after your procedure and once a year after that.

Activity

Your doctor will talk to you about activity restrictions related to recovery from the procedure.

Medications

Expect to take blood thinners for 6 to 12 months after surgery. If you had a stroke, you may need to take this medication indefinitely.

If you have another heart condition, you may need to take other medications.

You may need to take antibiotics before certain medical procedures for at least 6 months after your procedure to prevent an infection of your heart’s lining (endocarditis).